Most traders learn to respect “infrastructure risk” the hard way.

It usually doesn’t happen in a dramatic hack. It happens quietly. A dataset you depended on disappears. A project’s image servers go down during volatility. An on-chain dashboard suddenly can’t load historic charts because the file host behind it changed terms. Your thesis might still be right, but the plumbing fails and the trade becomes noise.

That’s the real problem decentralized storage is trying to solve: not just “where files live,” but whether the information layer underneath crypto can be relied on when incentives change and markets get stressed.

Walrus is one of the newer projects taking that challenge seriously, and it’s worth understanding as infrastructure, not as a narrative.

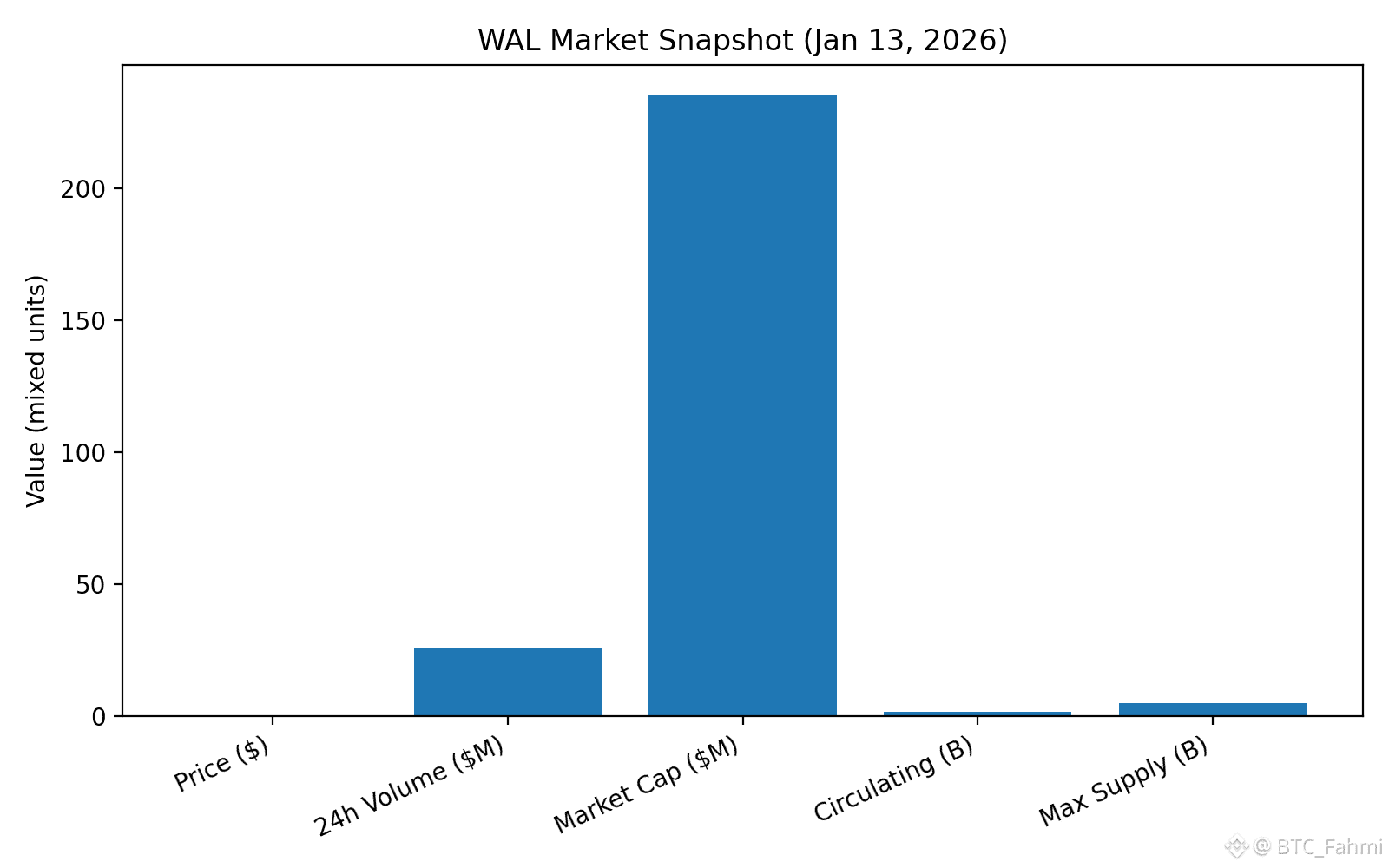

Today (January 13, 2026), WAL trades around $0.149 with roughly $26M 24h volume and about $235M market cap, with ~1.577B WAL circulating and 5B max supply. These numbers don’t “prove” anything about the protocol, but they do matter for investors in a practical way: it’s liquid enough to be tradable, and large enough that market participants are paying attention.

Now the real question: what obstacles exist in decentralized storage, and what does Walrus actually do differently?

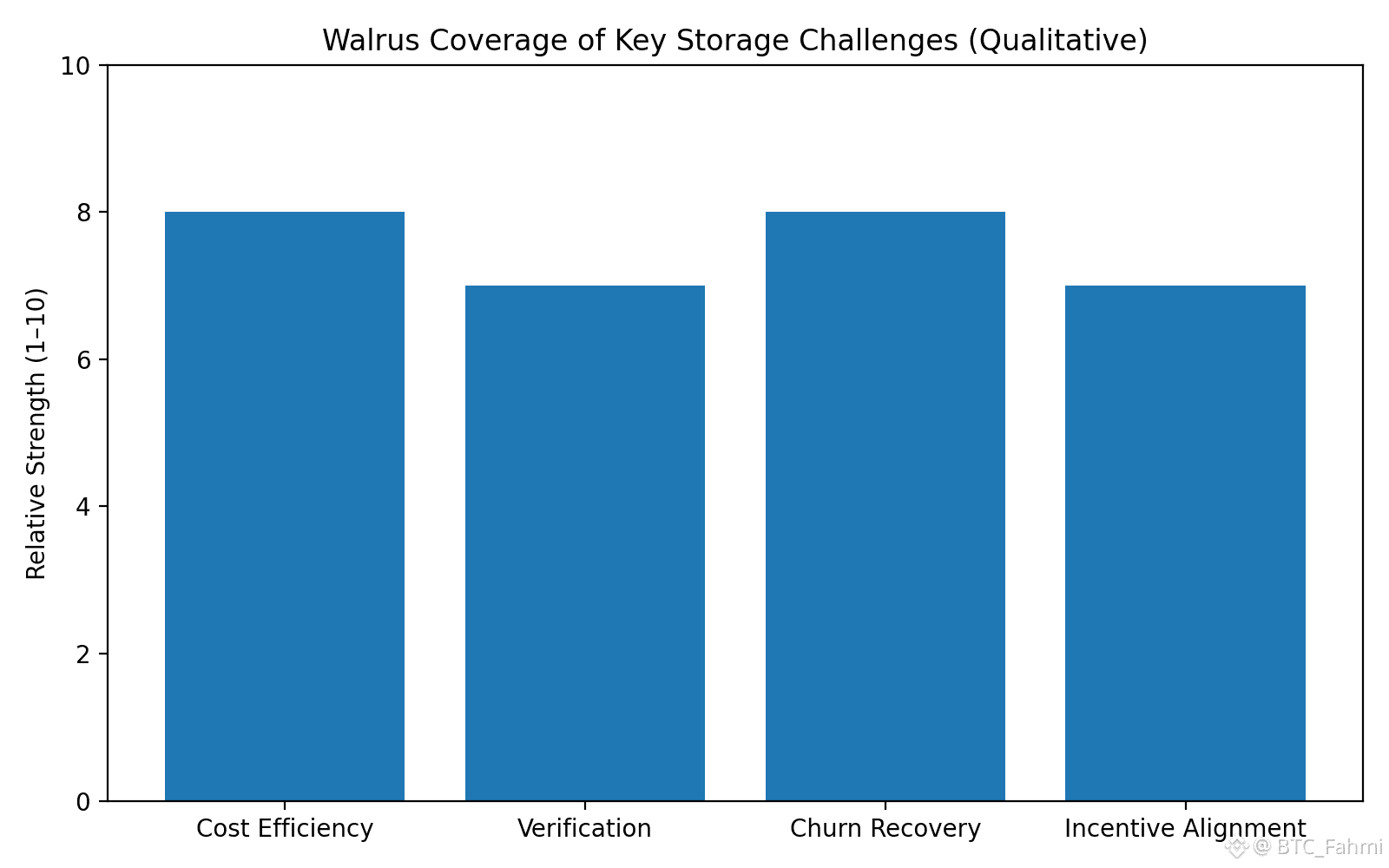

The first obstacle is simple economics. If you store data in a decentralized way by full replication (every node stores the full file), costs explode. That model works for blockchains storing transaction state, but it’s inefficient for “blob data” like videos, model files, NFT media, game assets, training data, and large logs. Walrus leans into erasure coding, meaning it breaks a file into encoded fragments so the original file can be recovered even if some pieces are missing. In Walrus documentation, they describe this as achieving cost efficiency by keeping storage overhead around ~5x the blob size—materially better than naïve replication approaches.

If you’ve ever run a trading community, you’ve already seen why that matters. Here’s a real-life style example many people will recognize: a private group builds strategies around a shared archive of market microstructure data, order-flow charts, and backtests. It’s too big for a blockchain and too valuable to keep on one cheap cloud server. The admin pays hosting fees, but then either (1) the bill becomes too large, (2) the host flags content, or (3) the admin quits, and suddenly everyone’s research layer is gone. It’s not just “lost files.” It’s lost edge. In trading, losing your information layer is like a market maker losing their pricing engine.

Walrus is built specifically for that sort of large-scale unstructured data, and it does so using Sui as a control plane. That matters: Walrus does not try to be a general blockchain. It tries to be specialized storage, while using on-chain coordination for lifecycle management and certificates that confirm availability. Their own description lays out this lifecycle: blobs are registered, space is acquired, data is encoded and distributed, and the system generates a Proof-of-Availability certificate onchain.

The second obstacle is not storage. It’s verification. In decentralized storage, the weakest point is always: “How do we know nodes actually kept the data?” The industry term is “proofs,” and this is where many systems become hand-wavy, because proving storage honestly under real network conditions is difficult.

Walrus explicitly frames this as a core security goal and introduced their approach to availability proofs and incentives, including rewards allocated to storage nodes and delegators each epoch, funded by storage fees and a bootstrap subsidy from the token supply. In other words, they’re not pretending altruism will keep the network alive. They’re designing around the fact that nodes are businesses and will behave like businesses.

The third obstacle is churn and recovery. Nodes go offline. Operators change strategy. Hardware fails. Market incentives shift, so participants leave. Many decentralized storage systems don’t fail because of a single catastrophic exploit; they degrade because recovery becomes too expensive, too slow, or too dependent on best-case assumptions.

Walrus claims one of its key innovations is a two-dimensional encoding method (“Red Stuff”) that enables self-healing recovery with bandwidth proportional to the lost data rather than re-downloading the entire blob. If you’re a trader, the analogy is portfolio hedging: you don’t want to rebuild the entire book after a small shock; you want localized repair. From an investor lens, this is the kind of design that makes storage networks less fragile under stress.

The fourth obstacle is governance and incentive alignment. Storage is long-duration by nature, while crypto incentives are often short-term. That mismatch is where networks get messy: operators chase rewards, users chase cheap fees, and long-term reliability becomes everyone’s second priority.

Walrus positions WAL as the tool for staking, governance, and securing node participation, with votes tied to staked amounts and penalties calibrated by the network. That doesn’t make it perfect, but it is at least an explicit recognition that storage markets need “credible commitments,” not just technology.

So what’s the unique angle for traders and investors?

Walrus should be viewed less like a typical L1 “throughput bet” and more like a bet on the expansion of data-heavy on-chain activity. That includes AI agent systems storing datasets, applications storing media, and ecosystems that treat storage capacity as a programmable asset. Walrus even frames storage capacity and blobs as objects that can be used inside smart contracts. If that design direction becomes common, storage becomes less like passive infrastructure and more like something composable—where apps don’t only use storage, but trade, allocate, and automate storage.

The reason this matters emotionally, not just technically, is that most people in crypto have experienced the disappointment of building on sand. A project can have brilliant token design and a clean UI, but if its data layer is centralized or fragile, it’s not durable. Over time, traders stop trusting that ecosystem, not because of ideology, but because unreliability feels like hidden leverage.

Walrus is not “the solution” to decentralized storage forever. No one is. But it is a serious attempt to deal with the hard parts: reducing replication waste through erasure coding, verifying availability with incentive-driven proofs, and handling real-world node churn without falling apart.

For long-term involvement, the practical monitoring list is simple: adoption by data-heavy apps, growth in stored blobs, the health of node participation, and whether incentives remain aligned when subsidies fade. That’s how you separate a storage network that looks good on paper from one that becomes real market infrastructure.

And for traders, that’s the quiet edge: infrastructure that doesn’t break is often what keeps a good thesis tradable.