@Walrus 🦭/acc A year ago, “storage pricing” felt like a niche argument for node operators and spreadsheet people. Lately it keeps creeping into product conversations because the bill for data is back, and the shape of that bill is changing. AI agents don’t just generate text; they save files, fetch context, and re-use data across workflows, which turns storage from a background detail into a product constraint. Walrus keeps showing up in that conversation because it positions storage as something apps can treat as programmable infrastructure rather than an off-chain afterthought. That shift—data as a first-class resource—makes pricing feel less like an accounting footnote and more like governance in disguise.

Walrus is a decentralized “blob” store coordinated through Sui smart contracts, which matters because it forces the network to be honest about what is being bought. You’re not paying a tiny fee every time someone references your data. You’re paying for the network to keep data available over time, across changing network conditions and changing incentives. That sounds obvious, but it’s the difference between paying for a taxi ride and paying for a transit system to reliably exist. The second one needs steering.

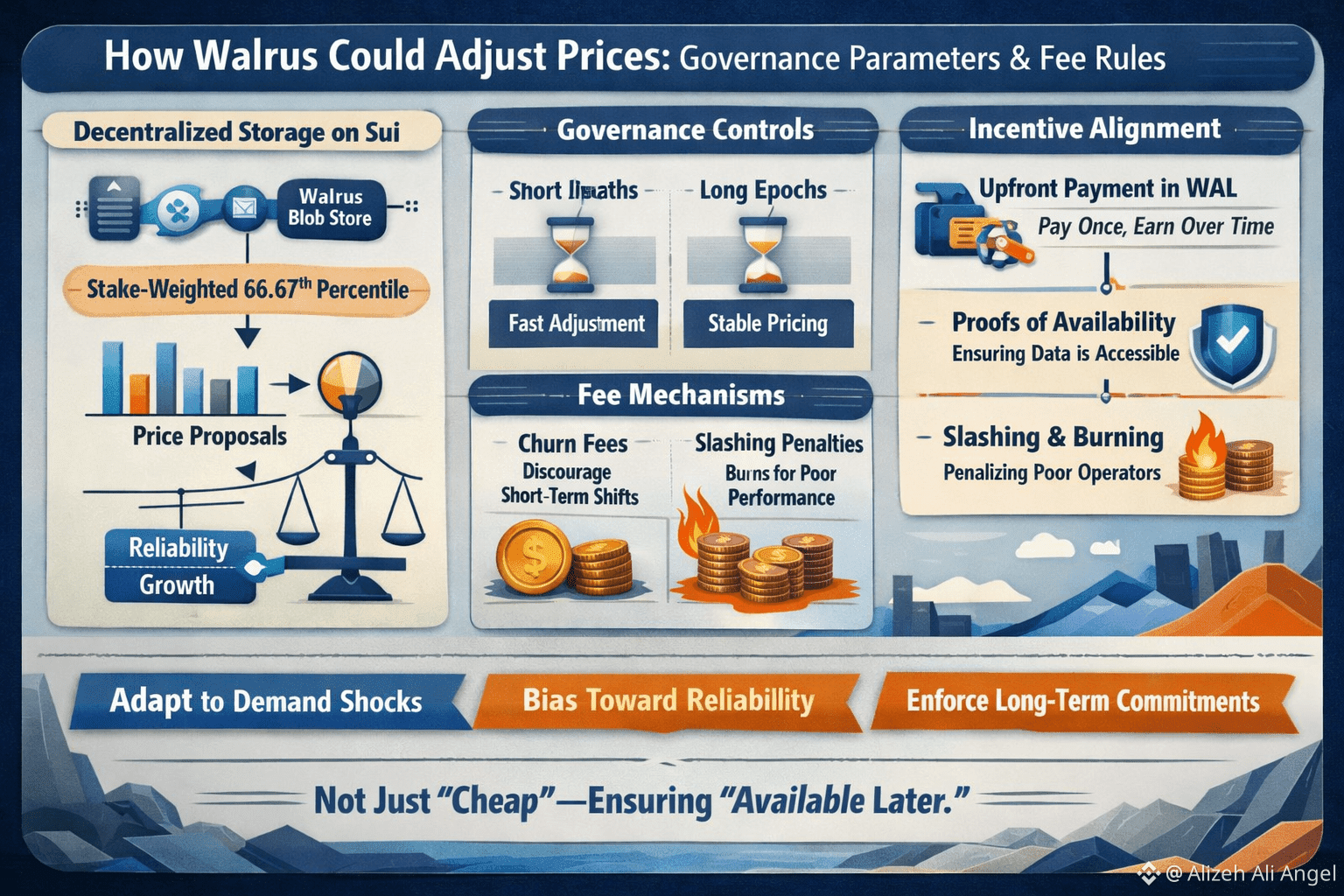

Walrus’s steering wheel starts with a surprisingly direct price-setting rule. At the beginning of each epoch, the storage committee proposes prices, and the protocol selects a stake-weighted 66.67th-percentile proposal rather than an average. The point isn’t mathematical elegance; it’s social realism. A simple average is easy to tug around with low-stake spam or coordinated underbidding. A stake-weighted percentile leans on the idea that if you have more at risk, your price signal deserves more weight—because you’re the one who gets punished if the network starts promising more storage than it can actually deliver.

Once you internalize that, “governance parameters” stop sounding abstract. They become a set of knobs that change who the network is for. Keep the percentile where it is and you’re committing to a bias toward reliability, because the selected price will tend to reflect what well-capitalized operators are willing to stand behind. Move that percentile up and you’re effectively asking users to pay more for a bigger safety margin. Move it down and you’re taking a growth bet: cheaper storage can attract experimentation, but it also invites operators who only survive if everything goes perfectly. Most networks don’t collapse from one dramatic failure; they soften first, quietly, until “sometimes it’s slow” becomes normal.

Epoch length is another knob that looks boring until you imagine a real shock. Shorter epochs let prices react faster when demand surges or when costs jump. Longer epochs give builders predictability, which matters if you’re shipping an app and don’t want your unit economics to change mid-sprint. Walrus’s own framing of storage as an intertemporal service—paid upfront, delivered across time—leans toward that predictability, but not at the cost of denial. The network has to update prices often enough that “stable” doesn’t mean “stale.”

The payment flow reinforces the same idea. Walrus uses WAL as the payment token, and when users buy storage for a fixed period, the payment is made upfront and then distributed over time to storage nodes and stakes. This design is easy to underestimate until you compare it to the way people experience cloud bills. Most teams don’t mind paying for storage; they mind surprises. Spreading compensation across time helps align rewards with the ongoing work of proving availability, rather than treating storage as a one-and-done sale that can be rationally abandoned later.

That brings us to fee rules—the part of economics that tends to feel unglamorous, yet it’s where networks either develop a spine or they don’t. Walrus describes churn fees to discourage short-term stake shifting, with a portion of that fee burned, and it describes slashing for poor performance with burning tied to penalties as well. Burning doesn’t magically create value, and I’m always a little wary when people talk about it like a religion. But as a governance tool, it’s plain: if the network wants long-term commitments, it has to make short-term gaming expensive enough that it stops being the default behavior.

There’s a subtler angle here that feels particularly relevant for Walrus because it’s trying to sit underneath apps, not just beside them. If you’re building an on-chain product that depends on off-chain data being there tomorrow, you don’t just care about average cost. You care about tail risk. You care about whether the network can recover from churn, faults, and operator turnover without quietly degrading. That’s why the conversation keeps circling back to proofs of availability and performance incentives: they’re not academic; they’re the mechanism by which price becomes a credible promise rather than a marketing number.

And yes, this is trending now for a concrete reason: Walrus has been past the “interesting idea” phase for a while and has been in the “people can actually use it” phase since its mainnet launch on March 27, 2025, following a widely covered token sale ahead of that date. Mainnet turns economic design into lived reality. It’s when builders start asking how prices move, operators start asking what behaviors get punished, and everyone realizes that governance isn’t a forum topic—it’s the part of the system that decides whether storage stays boring in the best way.

If Walrus gets price adjustment right, it won’t be because it found a perfect number. It’ll be because it treats pricing as network health management: update fast enough to reflect reality, bias toward operators who can actually deliver, and keep penalties sharp enough that reliability isn’t optional. In decentralized storage, “cheap” is easy to promise. “Available later” is a hard product.