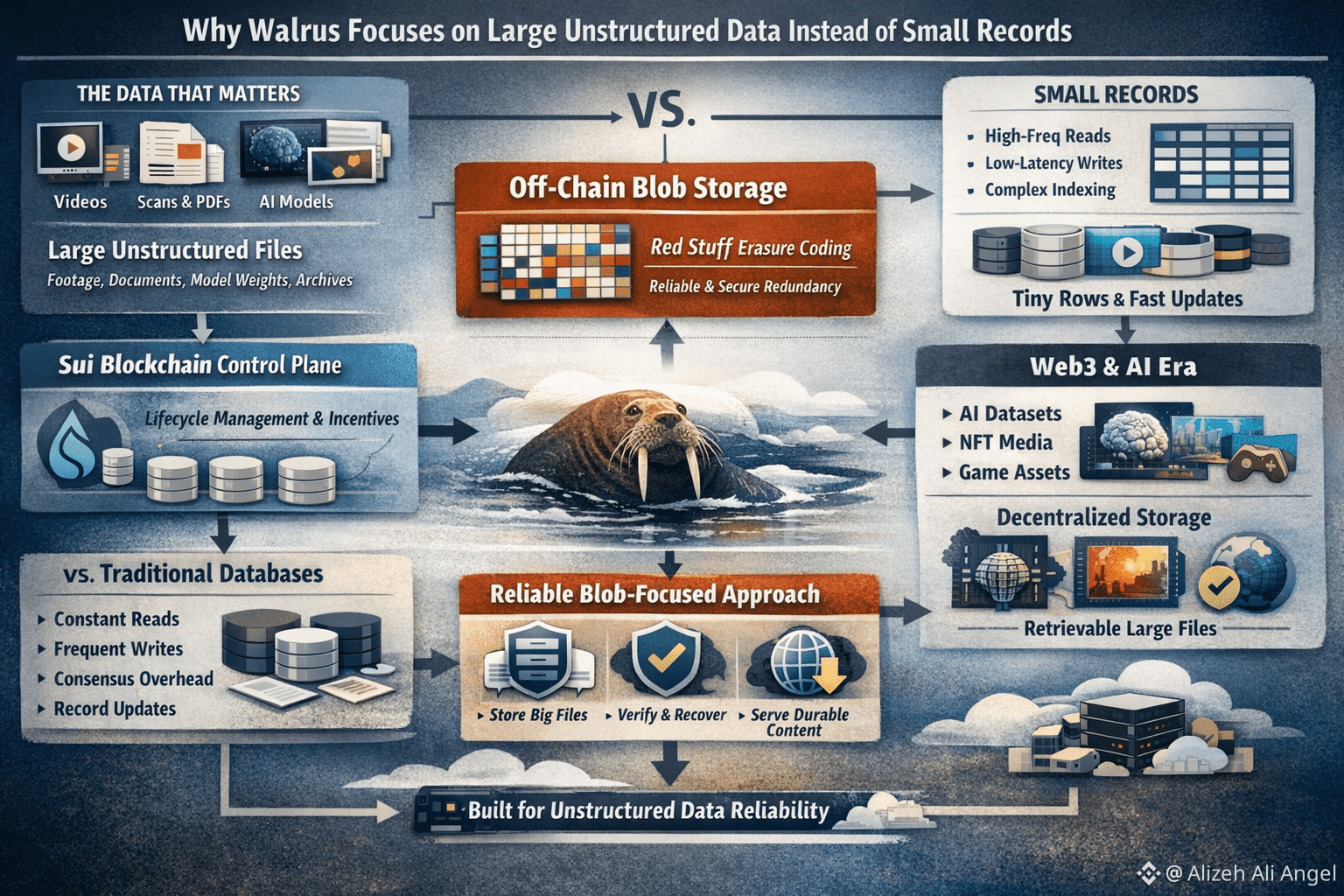

Walrus starts from a reality most modern teams bump into sooner than they expect: the data that actually matters isn’t always neat. It’s footage, scans, PDFs, design files, training corpora, model weights, and messy archives that come with partial labels and a lot of context trapped inside the file itself. Walrus treats that world as the default. It stores and serves large “blobs” off-chain, while using Sui as a control plane for lifecycle management and incentives, keeping the blockchain focused on coordination instead of hauling the bytes.

@Walrus 🦭/acc That focus makes more sense when you picture what “small records” require. A database optimized for tiny rows is built for high-frequency, random access: constant reads, frequent writes, tight indexing, and predictable query patterns. In distributed settings, you also pay for agreement—replicas need to converge on what’s current, which introduces coordination overhead that’s tolerable when the value is real-time queries and rapid updates. But if your core job is simply “store this big file reliably and let anyone fetch it later,” a lot of that machinery becomes weight you’re carrying for no reason. Walrus is drawing a clean line: it isn’t trying to be a universal database, because the physics and economics of that job are different.

Large unstructured files flip the cost equation. When the object is huge, the bottleneck isn’t usually “can we index this faster,” it’s “can we move and preserve these bytes without paying full price every time something goes wrong.” Walrus leans into redundancy that’s smarter than plain replication. At the heart of the system is Red Stuff, a two-dimensional erasure coding scheme designed for high resilience with a relatively low overhead, and with recovery costs that scale with what was actually lost, not the entire blob.

What’s quietly interesting is that Red Stuff isn’t framed only as an efficiency trick; it’s also a security answer. The Walrus paper emphasizes “storage challenges” that work even under asynchronous network conditions, so an adversary can’t exploit timing and delays to pretend they’re storing data when they aren’t. That’s a very specific problem to solve, and it signals where Walrus expects to be used: environments where independent parties need to rely on availability guarantees without trusting a single operator.

If you try to apply the same approach to millions of tiny records, the trade-offs get ugly fast. Tiny-record systems demand low-latency key lookups, fast conditional writes, and consistent behavior under a constant churn of updates. Breaking everything into coded pieces and distributing them across many nodes can create a storm of fragments and proofs, and you still haven’t handled the core “database” promise: give me this record right now, and let me change it safely a second later. Walrus can store small files, but its design decisions—coding, distribution, recovery, and verification—are calibrated for blob-scale objects where throughput and availability dominate, not row-level transactions.

The reason this feels timely is that we’re in a very “blob-shaped” era of computing. AI is a big driver, not because it’s trendy in the abstract, but because production AI runs on piles of documents and media that are too large to keep duplicating across teams and too valuable to leave as fragile links. Walrus itself positions the protocol as infrastructure for AI datasets and autonomous-agent style applications that need to store and retrieve large unstructured inputs and artifacts.

Web3 adds another pressure. On-chain state is great for small, high-value records—ownership, balances, permissions, the minimal facts a smart contract needs. But the “bulky truth” of an application lives elsewhere: NFT media, game assets, website frontends, archives, and proofs that may be expensive to replicate everywhere. Mysten Labs explicitly framed Walrus as decentralized storage plus data availability, with examples that include hosting rich media and supporting applications that need large artifacts to remain retrievable.

What I find most convincing about this whole direction is how ordinary the underlying pain is. People rarely complain that storing a 200-byte record is impossible. They complain that the dataset they trained on can’t be audited later, that the media behind an NFT disappeared, that a “permanent” website depends on a vendor account staying in good standing, or that a game’s downloadable assets keep turning into broken pointers. Walrus’ emphasis on programmable, verifiable blob storage feels like a response to those real-world failure modes, not a philosophical preference for “big data.” Even the way Walrus talks about hosting and serving content—like decentralized websites—signals a practical goal: make large content durable and usable, not just theoretically stored.

So the choice to prioritize large unstructured data isn’t a dismissal of small records. It’s a boundary that keeps the system honest. Databases should keep doing what they do best. Blockchains should store only what they must. And protocols like Walrus can specialize in the heavy, awkward files that modern applications increasingly depend on—files that don’t fit into rows, but still deserve to be reliable, recoverable, and independently verifiable.