Walrus is showing up everywhere in Sui circles lately, and I don’t think it’s because people suddenly got excited about storage as a category. It’s because the center of gravity has shifted. When teams talk about onchain games, AI agents, media archives, or data markets, they’re really talking about a pile of big files that don’t fit neatly inside a blockchain block. For years, the usual answer was a hash and a link. That works until you need stronger guarantees than “somebody is probably hosting this,” and until you realize that, for many products, the data itself is the product.

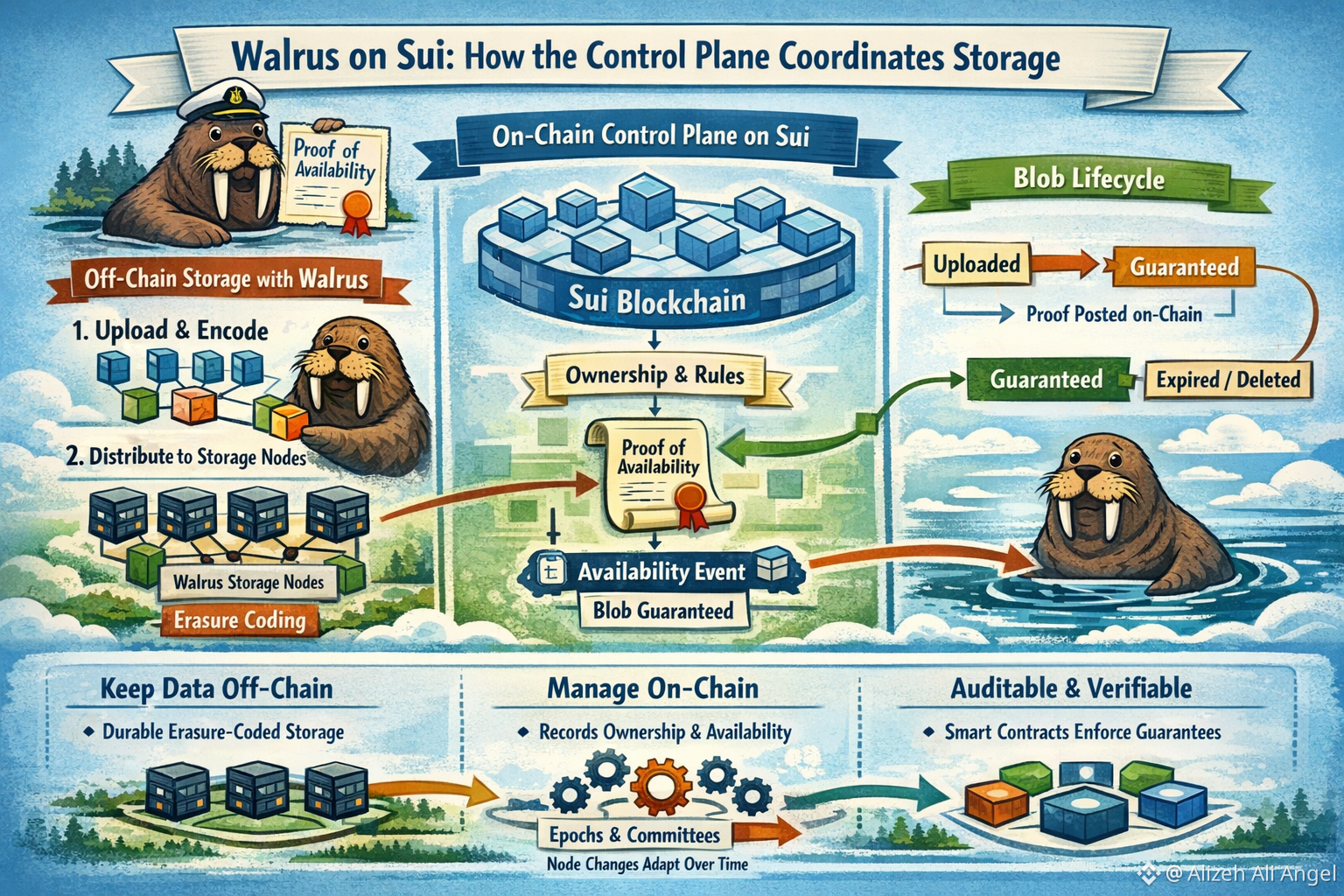

Walrus pushes a clearer separation of duties: keep the bytes off-chain, but keep the promises on-chain. In practice, Sui becomes the control plane where rules, ownership, and status are recorded, while Walrus storage nodes handle the heavy lifting of holding encoded data. Walrus describes each stored “blob” as having an onchain representation on Sui, with the key idea being that blob ownership maps cleanly onto object ownership, so applications can reason about access and lifecycle without inventing a parallel permission system.

The most concrete place where that coordination shows up is the moment a blob transitions from “uploaded” to “guaranteed.” Walrus calls this the point of availability: a client (often via a relay) registers metadata, breaks the blob into encoded pieces, sends those pieces to storage nodes, and collects acknowledgements. Once the client posts an onchain Proof-of-Availability certificate to Sui, the network treats the blob as an obligation for the paid duration. The docs even tie this to an “availability event” that marks when the guarantee begins, which is a small detail that matters because it gives developers a crisp line they can build product logic around.

If you zoom out, it’s basically a shift from “storage as a best-effort service” to “storage as an auditable contract.” That framing sounds abstract, but it changes day-to-day engineering decisions. You can build flows where minting an NFT, publishing a post, or unlocking a game asset is conditional on an onchain fact: the blob has a recorded certificate and a defined lifetime. You stop asking users to trust that a gateway will keep working, and you start giving them something closer to a receipt that the rest of the system can verify.

Of course, a receipt is worthless if the warehouse quietly collapses. Walrus tackles the hard part with erasure coding rather than full replication, aiming for durability without the cost of storing complete copies everywhere. The project’s research paper describes Walrus as an erasure-coded blob network built to scale to hundreds of storage nodes, and it highlights “Red Stuff,” a two-dimensional encoding approach meant to be resilient and “self-healing” when pieces go missing. Walrus documentation puts the tradeoff in plain terms: encoded parts are distributed across nodes, and the storage overhead is on the order of about five times the original blob size, which is still far below the “replicate everything everywhere” approach that makes many systems buckle under real media workloads.

That brings us back to the control plane. Walrus isn’t just a protocol for cutting files into fragments; it’s also a protocol for coordinating membership and responsibility over time. The paper discusses how the system is designed around committees of storage nodes and epoch-style changes, so the network can keep operating even as nodes churn, stakes shift, or machines fail. In human terms, the control plane is there to answer the awkward questions that storage systems hate: Who is responsible right now? What exactly are they responsible for? And what happens when the set of responsible parties changes?

This is also why Walrus is trending now rather than six months later or two years earlier. The protocol moved from “interesting design” to “people can actually ship with it” when it launched public mainnet on March 27, 2025, and it anchored that launch with a story about programmable storage, not just cheaper storage. Around the same time, the $140 million private token sale pulled Walrus into a much wider conversation, with mainstream coverage emphasizing both the size of the round and the fact that the network was built on Sui and developed out of the Mysten ecosystem. Big money doesn’t make tech good, but it does force more people to read the fine print—and Walrus has enough fine print to reward the effort.

What I find most educational, though, is where the model is honest about its limits. Deletion and expiry in Walrus are availability guarantees, not a magical privacy switch; if someone copied the bytes, the chain can’t un-copy them. The more practical limitation is product design: reading and writing blobs can involve multiple requests and moving parts, which is why apps end up leaning on relays, indexers, and caching layers. Sui’s own developer documentation shows how an application might treat the “liveness” of a Blob object on Sui as the signal for whether content should be considered accessible, even acknowledging that the underlying blob might still physically exist on Walrus after the object is wrapped or deleted. That’s a subtle but important separation between “data exists somewhere” and “the app considers it available.”

In the end, Walrus feels like progress because it makes storage legible. It turns “did it stick?” into something you can point at, verify, and build rules around. And in a world where more applications are really data products wearing a blockchain costume, that kind of clarity is oddly refreshing.