I remember the moment I first got curious about node churn and why it keeps surfacing in conversations about decentralized storage. It’s not glamorous, but it’s where theory meets reality. Nodes leave. Nodes join. Hardware fails. Networks hiccup. And the system still has to keep your data available. For traders and investors who depend on reliable access to large off-chain datasets, custody records, or historical market data, this isn’t an abstract engineering issue. It’s operational risk. Walrus has been part of this discussion since its mainnet launch in March 2025, and the way it approaches churn is one of the more interesting developments in storage infrastructure.

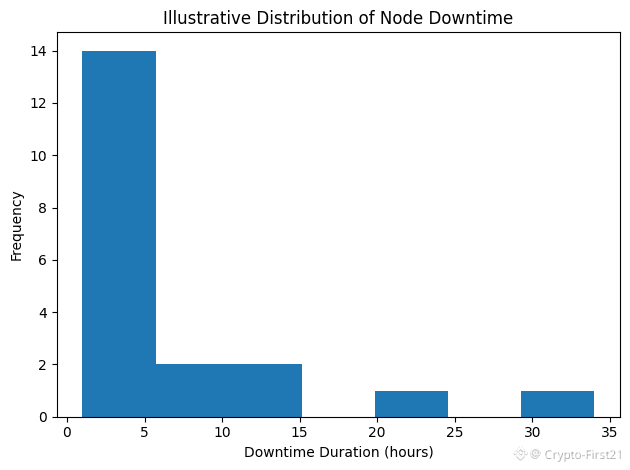

Node churn is simple to define. In a decentralized network, a node is a machine operated by an independent party that stores data. Churn describes how often those machines go offline and get replaced. Some outages are temporary. Others are permanent. In centralized systems, churn is hidden inside a data center with redundant power, networking, and staff. In decentralized systems, churn happens in the open, across home servers, cloud providers, and colocation racks spread around the world. Every departure forces the network to repair itself, and repair is where cost, bandwidth, and time pile up.

Walrus was designed with this problem front of mind. Instead of relying on full replication, it uses an erasure-coded storage model. In simple terms, files are split into pieces, and only a subset of those pieces is needed to recover the original data. When a node disappears, the system reconstructs only the missing pieces rather than copying the entire file again. That distinction sounds technical, but economically it’s meaningful. Repair traffic consumes bandwidth, and bandwidth is one of the most expensive recurring costs in decentralized networks.

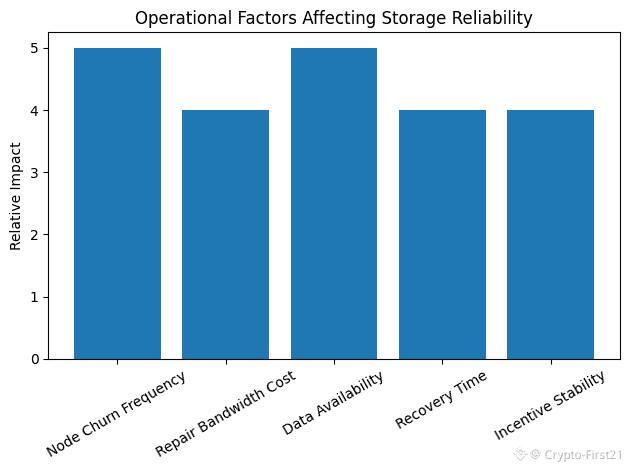

From a trader’s perspective, the question is not whether repair happens, but how disruptive it is. Imagine a fund running automated strategies that depend on large datasets stored off-chain. If the storage network is busy copying full replicas after a few nodes drop out, retrieval times can spike exactly when markets are volatile. Slippage doesn’t always come from price movement. Sometimes it comes from systems not responding on time. Walrus’s approach tries to reduce that risk by keeping repair traffic proportional to what’s actually lost, not to the full size of the data.

This focus on churn is one reason Walrus gained attention quickly after launch. By early 2025, the scale of data used in crypto had changed. Storage networks were no longer dealing with small metadata blobs alone. AI models, gaming assets, video files, and compliance records all demand persistent, high-volume storage. Replication-heavy systems handle churn by brute force, which works but becomes expensive and noisy at scale. Walrus entered the market with the argument that smarter repair matters more than raw redundancy once networks grow.

The project also had the resources to test that argument. In March 2025, Walrus announced a roughly 140 million dollar funding round. For traders, funding announcements are often treated as noise. For infrastructure, they matter. Engineering around churn is not cheap. It requires testing under failure, audits, monitoring, and time to iterate. Capital allows a team to measure real-world behavior instead of relying purely on theory. From an investor’s standpoint, that funding suggested Walrus was planning for a long operational runway rather than a short-lived launch cycle.

That said, erasure coding doesn’t eliminate churn problems. It changes them. While it reduces storage overhead and repair bandwidth, it increases coordination complexity. Nodes must track metadata precisely. Repair logic must be robust. If the network has too many unreliable operators, recovery can still lag. This is where Walrus’s broader design comes into play. The protocol includes epoch-based coordination and committee mechanisms designed to manage node membership changes without destabilizing availability. For institutions evaluating infrastructure, those mechanics are often more important than headline throughput numbers.

Incentives are the quiet driver behind all of this. Nodes don’t stay online out of goodwill. They stay online because the economics make sense. Walrus distributes rewards over time and ties compensation to availability and correct behavior. The goal is to reduce churn by aligning operator incentives with network health. In my experience, this alignment is what separates sustainable infrastructure from systems that slowly decay as operators churn out. A network that pays generously but unpredictably still creates risk. Predictable rewards tied to measurable performance are what keep operators invested.

Why is this trending now? Because the market is shifting its attention from experimentation to reliability. As more capital flows into tokenized assets and automated strategies, the tolerance for infrastructure failure shrinks. Storage is no longer a background service. It’s part of the settlement stack. Walrus has been trending because it frames storage reliability as an engineering and economic problem, not just a cryptographic one, and backs that framing with a live network and published design details.

Progress since launch has been incremental rather than flashy. The network has focused on onboarding storage providers, refining repair logic, and publishing documentation around how data is stored and recovered. That kind of progress rarely makes headlines, but it’s what traders and developers should pay attention to. Infrastructure that works quietly under stress is more valuable than infrastructure that promises extreme performance in ideal conditions.

There are still open questions. How does the system behave under correlated failures, such as regional outages or major cloud disruptions? Does repair remain efficient as node geography becomes more diverse and latency increases? Can incentive mechanisms continue to discourage churn as the network scales and operator profiles diversify? These are not criticisms. They are the natural questions any serious infrastructure project must answer over time.

From a practical standpoint, traders and investors should start factoring storage reliability into their risk models. It’s not enough to ask whether a token is liquid. You should ask whether the data your strategy depends on will be available during stress. Metrics like recovery time, repair bandwidth, and uptime under churn are just as relevant as block times or fees. Storage failures don’t always announce themselves loudly. Sometimes they show up as subtle delays that compound into losses.

On a personal level, I’ve seen too many technically elegant systems struggle with messy operational realities. Hardware breaks. Operators misconfigure servers. Incentives drift. What makes Walrus interesting is not that it claims to eliminate these problems, but that it treats them as first-order design constraints. Node churn isn’t an edge case. It’s the norm. Designing around that reality is what makes infrastructure usable for serious capital.

In the end, storage networks are plumbing. You don’t notice them when they work, but everything downstream depends on them. Walrus’s focus on the engineering reality of node churn reflects a broader maturation in crypto infrastructure. For traders and investors, that shift matters. Reliability is not exciting, but it’s what allows markets to function when conditions are less than perfect.