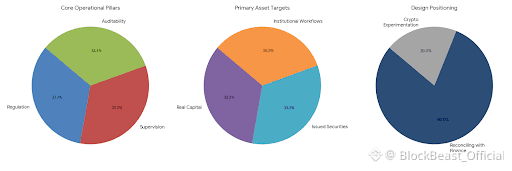

Founded in 2018, Dusk positions itself less as an experiment in cryptography and more as an attempt to reconcile distributed systems with the realities of regulated finance. That distinction matters. Many blockchain projects are conceived in opposition to existing financial structures, implicitly assuming that regulation, supervision, and auditability are temporary obstacles rather than permanent conditions. Dusk’s design choices suggest a different starting assumption: that any system intended to handle real capital, issued securities, or institutional workflows will eventually be inspected, constrained, and held accountable by external authorities. The protocol appears built with that inevitability in mind.

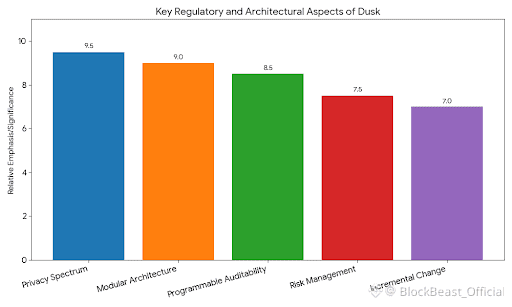

From a regulatory perspective, the most notable aspect of Dusk is its treatment of privacy. Rather than framing privacy as an absolute state—where transactions are either fully opaque or fully transparent—the architecture treats it as a spectrum of disclosure. This reflects how privacy actually operates in financial systems today. Banks, custodians, and market infrastructures do not offer anonymity; they offer confidentiality with conditions. Information is concealed from the public but selectively disclosed to auditors, regulators, or counterparties when legally required. Dusk’s emphasis on selective disclosure and programmable auditability mirrors this reality. Privacy is not presented as resistance to oversight, but as a controlled mechanism that can coexist with supervision. This is not a compromise born of regulatory pressure; it is an acknowledgment that durable financial infrastructure cannot depend on perpetual invisibility.

The modular nature of the system reinforces this conservative posture. Separating consensus from execution, and allowing components to evolve independently, is not an exercise in technical elegance so much as a risk-management strategy. In traditional financial infrastructure, decoupling components reduces blast radius when failures occur. Payment rails, messaging layers, and settlement systems are often distinct precisely because upgrades, incidents, or regulatory changes rarely affect all layers simultaneously. Dusk’s architectural separation follows a similar logic. It allows for incremental change without forcing a wholesale rewrite of the system, an important consideration when applications are expected to operate continuously and predictably over long periods.

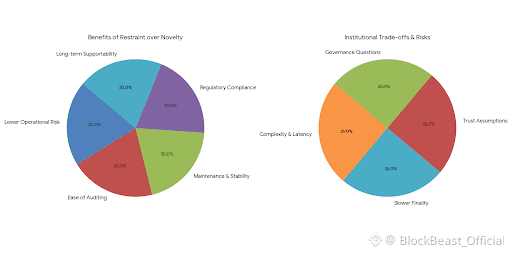

Compatibility with existing developer tools and established programming paradigms is another example of restraint over novelty. Rather than requiring specialized languages or esoteric environments, the platform appears to prioritize familiarity. This lowers the operational risk associated with hiring, auditing, and maintaining production systems. In regulated environments, developer turnover, third-party audits, and external reviews are routine. Tooling that deviates too far from industry norms becomes a liability, not an advantage. Familiarity may slow innovation at the margins, but it significantly improves the odds that systems can be understood, reviewed, and supported years after deployment.

None of these decisions are without trade-offs. Privacy-preserving computation and selective disclosure mechanisms tend to introduce additional complexity and, often, latency. Settlement finality may be slower than on chains optimized purely for throughput. Cross-chain interactions and asset migrations rely on trust assumptions that cannot be eliminated, only managed. Bridges, custody models, and upgrade paths introduce governance questions that are uncomfortable but unavoidable. From an institutional standpoint, these are not disqualifying flaws; they are factors that must be priced into risk assessments and operational planning. Pretending they do not exist is far more dangerous than acknowledging them openly.

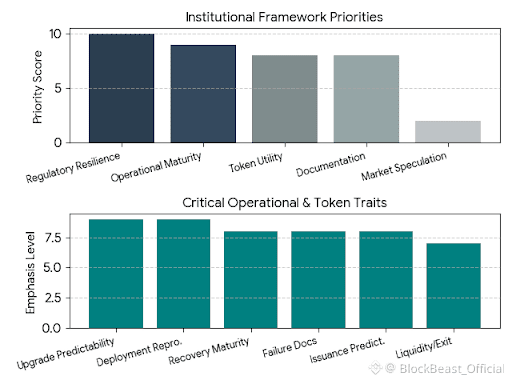

Operational details—often overlooked in early-stage protocols—carry disproportionate weight in environments subject to audits and compliance reviews. The predictability of node upgrades, the clarity of documentation, and the maturity of monitoring and recovery tooling determine whether a system can be run by a risk committee rather than a hobbyist. Dusk’s long-term viability will depend less on headline features and more on whether operators can answer mundane but critical questions: How disruptive is an upgrade? How reproducible are deployments? How clearly are failure modes documented? These considerations rarely generate excitement, but they are decisive when systems move from pilot programs to production use.

The token design, when viewed through an institutional lens, is similarly unglamorous. Liquidity matters not as a vehicle for speculation, but as a mechanism for entry and exit without distorting markets. Predictable issuance, clear utility, and the absence of aggressive incentive schemes reduce the risk of misalignment between network participants and application builders. Institutions are less concerned with upside narratives than with whether they can unwind positions, hedge exposure, or comply with balance sheet constraints without unexpected friction. A token that behaves more like infrastructure fuel than a speculative asset is more likely to fit within existing financial frameworks.

Taken together, Dusk reads as infrastructure built by people who expect scrutiny rather than attention. Its design philosophy suggests an understanding that success, in this context, is not measured by visibility or rapid adoption curves, but by the ability to endure audits, regulatory change, and operational stress over time. Systems intended for regulated finance do not need to be revolutionary; they need to be reliable, legible, and resilient. If Dusk succeeds, it will likely do so quietly—by functioning as intended, under constraints that others prefer to ignore.