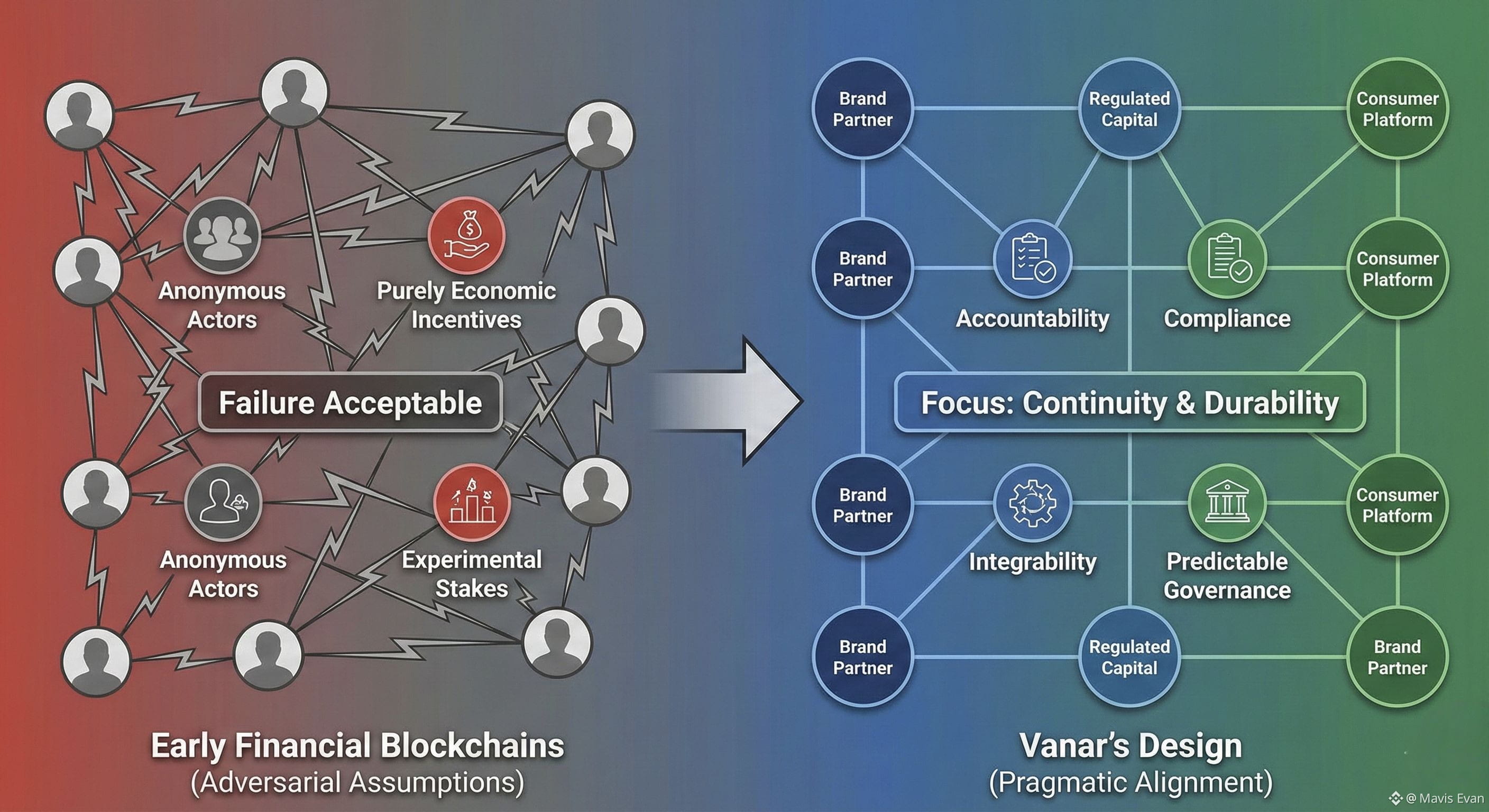

Before blockchains were discussed as consumer platforms or cultural infrastructure, they were framed as financial systems. That origin still shapes many of the structural problems the industry struggles with today. Most public blockchains were designed around adversarial assumptions: anonymous actors, purely economic incentives, and environments where failure is acceptable because the stakes are experimental. That model works for permissionless experimentation, but it breaks down when real businesses, brands, and regulated capital are involved. When reputational risk matters, when users are not crypto-native, and when systems must behave predictably under scrutiny, the assumptions that power early blockchains become liabilities rather than strengths.

The core problem is not scalability in isolation, nor is it simply user experience. It is misalignment between how blockchains behave and how real-world organizations operate. Enterprises and consumer platforms do not optimize for ideological purity. They optimize for continuity, accountability, compliance, and the ability to integrate with existing legal and operational frameworks. Most layer-1 blockchains struggle here because their architectures were never designed to host applications tied to brands, intellectual property, or large user bases that expect reliability and clear governance boundaries. In practice, this has limited adoption to niches where failure is tolerated and responsibility is diffuse.

Vanar can be understood as a response to this gap rather than an attempt to overturn existing models. Its design choices reflect a pragmatic acknowledgement that Web3 adoption will not come from abstract ideals, but from systems that make sense to organizations already operating at scale. The team’s background in gaming, entertainment, and brand partnerships is relevant here, not as a marketing credential, but because these industries operate under constraints that crypto systems often ignore. Games, media platforms, and consumer brands deal with millions of users, strict licensing rules, and reputational exposure that cannot be abstracted away.

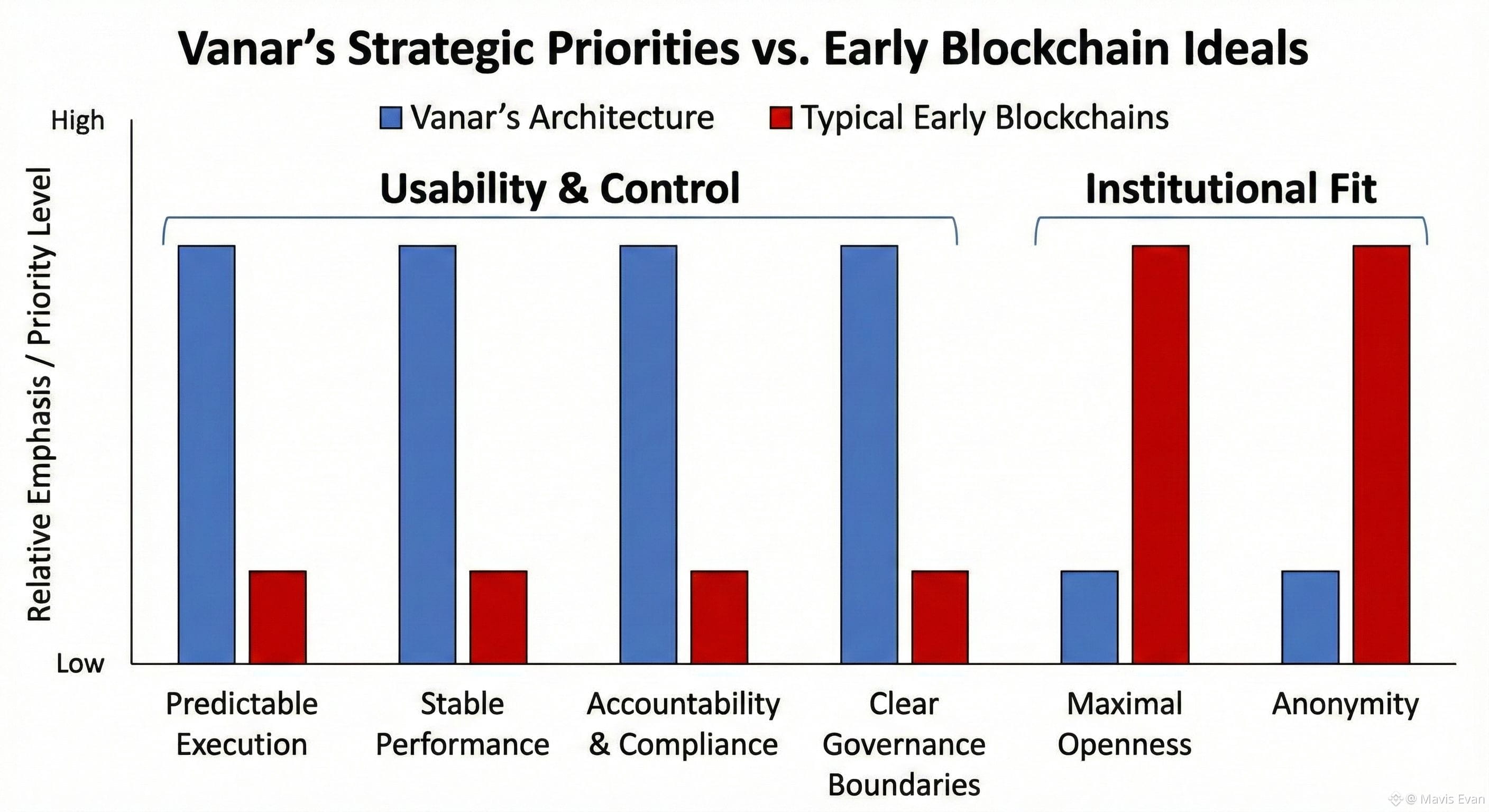

Rather than treating decentralization as an end in itself, Vanar approaches it as a constraint to be balanced against usability and control. Its layer-1 architecture is built to support applications that look familiar to mainstream users while still benefiting from blockchain-based settlement and coordination. This means prioritizing predictable execution, stable performance, and clear application boundaries over maximal openness. The trade-off is intentional: some forms of composability and permissionlessness are constrained in exchange for systems that brands and platforms can realistically deploy without exposing themselves to unacceptable operational risk.

At a conceptual level, Vanar’s architecture emphasizes separation of concerns. Execution environments are designed to support high-throughput consumer applications, while settlement and validation focus on maintaining consistency and finality rather than constant experimentation. Privacy and identity considerations are framed around practical needs such as user management, compliance, and content control, not absolute anonymity. This reflects how real institutions think about risk. Total transparency is rarely desirable, but neither is total opacity. What matters is controlled visibility, auditability, and the ability to respond to issues when they arise.

Consider a gaming publisher issuing in-game assets that have secondary market value. On many existing blockchains, this immediately creates conflicts around compliance, user protection, and brand risk. If assets are freely transferable without guardrails, the publisher loses control over how its intellectual property is used. If transactions are fully public and immutable, mistakes become permanent liabilities. Vanar’s design allows such assets to exist within a framework where rules can be enforced consistently, audits are possible, and user behavior aligns with the expectations of a regulated consumer product. This is less about innovation and more about fitting blockchain logic into established commercial realities.

A similar logic applies to digital collectibles, brand tokens, or metaverse platforms like Virtua. These are not financial experiments; they are extensions of existing entertainment and licensing models. For them to function at scale, the underlying infrastructure must support predictable governance, content moderation, and lifecycle management. Vanar positions itself as infrastructure that can host these activities without forcing operators to choose between full centralization and uncontrolled decentralization.

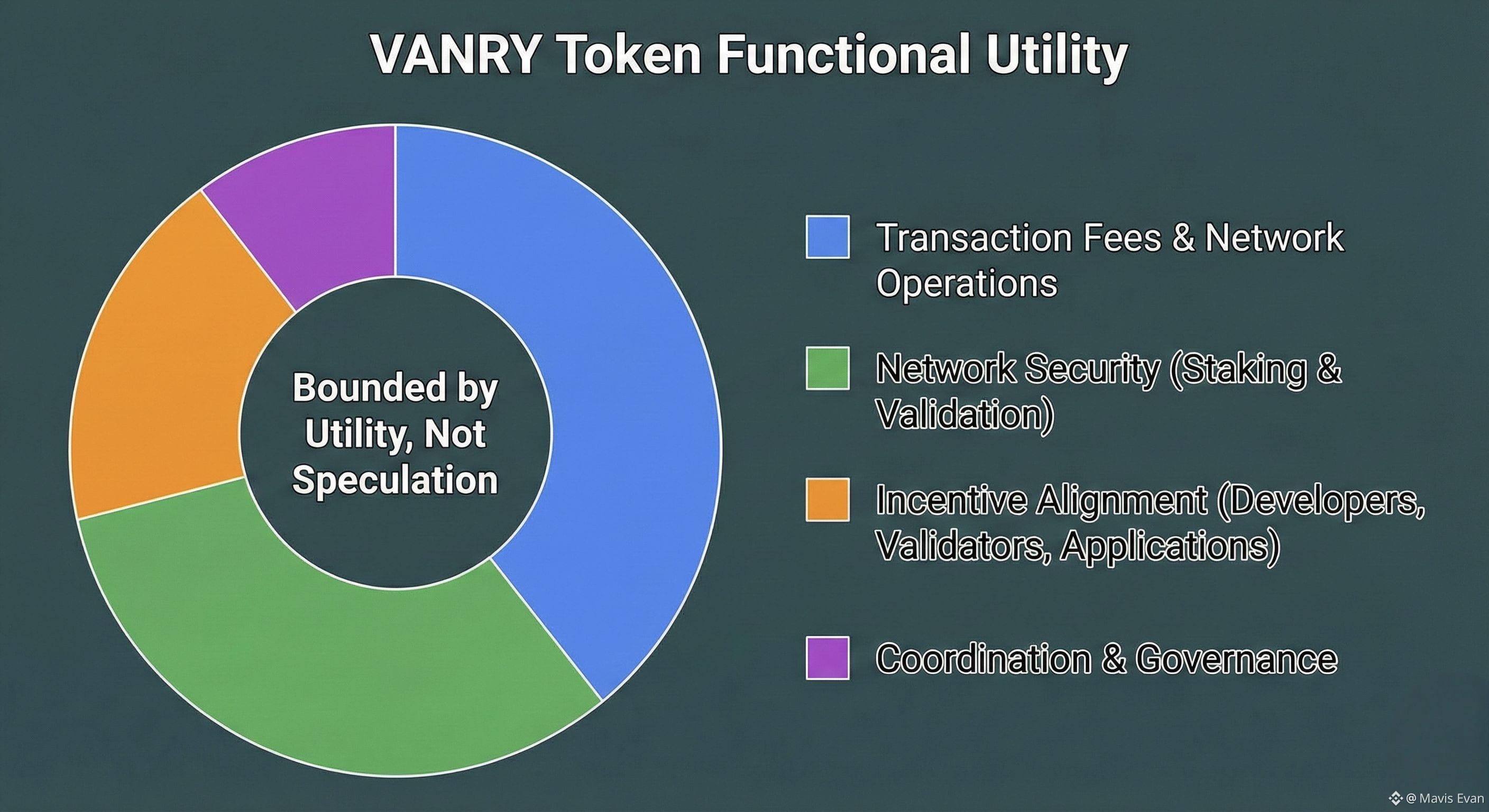

The VANRY token plays a functional role within this system rather than serving as a speculative instrument. It is used for transaction fees, network security, and coordination between participants who maintain and build on the network. Its purpose is to align incentives between validators, developers, and applications, ensuring that the network remains operational and economically sustainable. Importantly, its role is bounded by utility. It exists to support behavior on the network, not to define the network’s value proposition.

In the broader context of blockchain evolution, Vanar represents a category of systems that are less concerned with ideological debates and more focused on durability. As the industry matures, the question is no longer whether blockchains can exist outside traditional systems, but whether they can coexist with them in a way that is stable and credible. Projects that acknowledge institutional constraints, regulatory realities, and consumer expectations are more likely to persist, even if they attract less attention in speculative cycles.

Vanar’s relevance, then, lies not in grand claims about transforming finance or culture, but in its alignment with how large-scale platforms already operate. By treating blockchain as infrastructure rather than spectacle, it positions itself as part of a gradual integration of Web3 into existing economic and cultural systems. That path is slower and less dramatic, but it is also the one most consistent with how lasting financial and technological systems have historically been built.