The first thing to understand about Walrus is that it didn’t emerge from hype. It emerged from pressure. The quiet, grinding pressure of a digital world that keeps producing more data than its foundations were ever meant to hold. Not tweets or transactions, but heavy things: training datasets, game worlds, medical images, archives that need to exist tomorrow exactly as they existed today. For years, blockchains promised permanence but choked on size. Cloud storage promised scale but demanded trust. Walrus was born in the narrow, uncomfortable space between those two failures, shaped less by ideology than by necessity.

To grasp what Walrus is trying to do, you have to zoom out and then back in. At the macro level, it is a storage protocol. At the micro level, it is an argument about how trust should be distributed in a networked world. It runs on Sui, a blockchain designed for speed and parallelism, but Walrus itself is not a chain and not a cloud. It is something stranger: a system that treats large data objects—blobs, in the language of engineers—as first-class citizens, giving them identity, verifiability, and economic weight without forcing them to live directly on-chain.

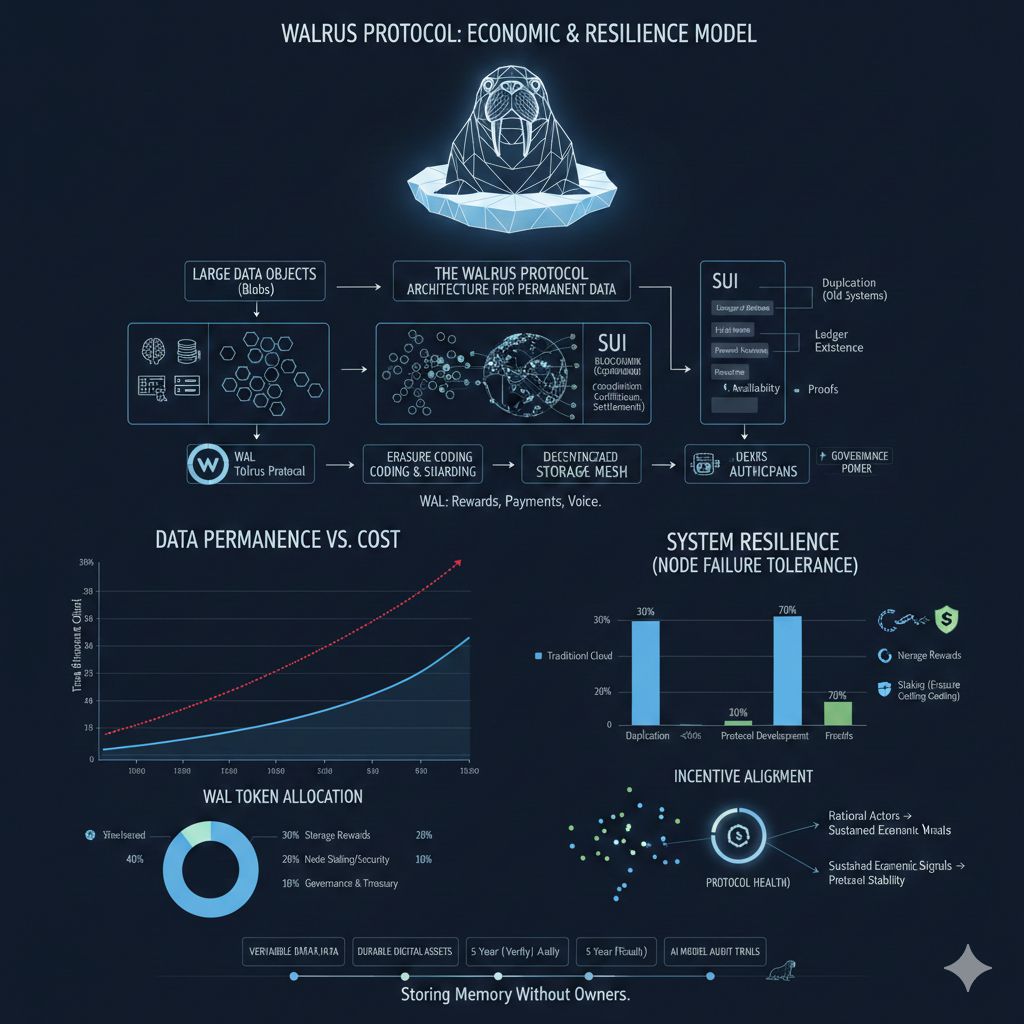

The core idea is deceptively simple. Instead of storing a file whole, Walrus breaks it apart, encodes it, and scatters it across a decentralized network. No single node holds the full object. No single failure destroys it. Enough fragments, retrieved from enough places, can reconstruct the whole. This is erasure coding, an old concept refined into something more agile and more political. Old systems duplicated data endlessly, trading safety for waste. Walrus trades duplication for math. It assumes failure is normal, nodes will disappear, and networks will wobble. The system is designed to survive that reality rather than deny it.

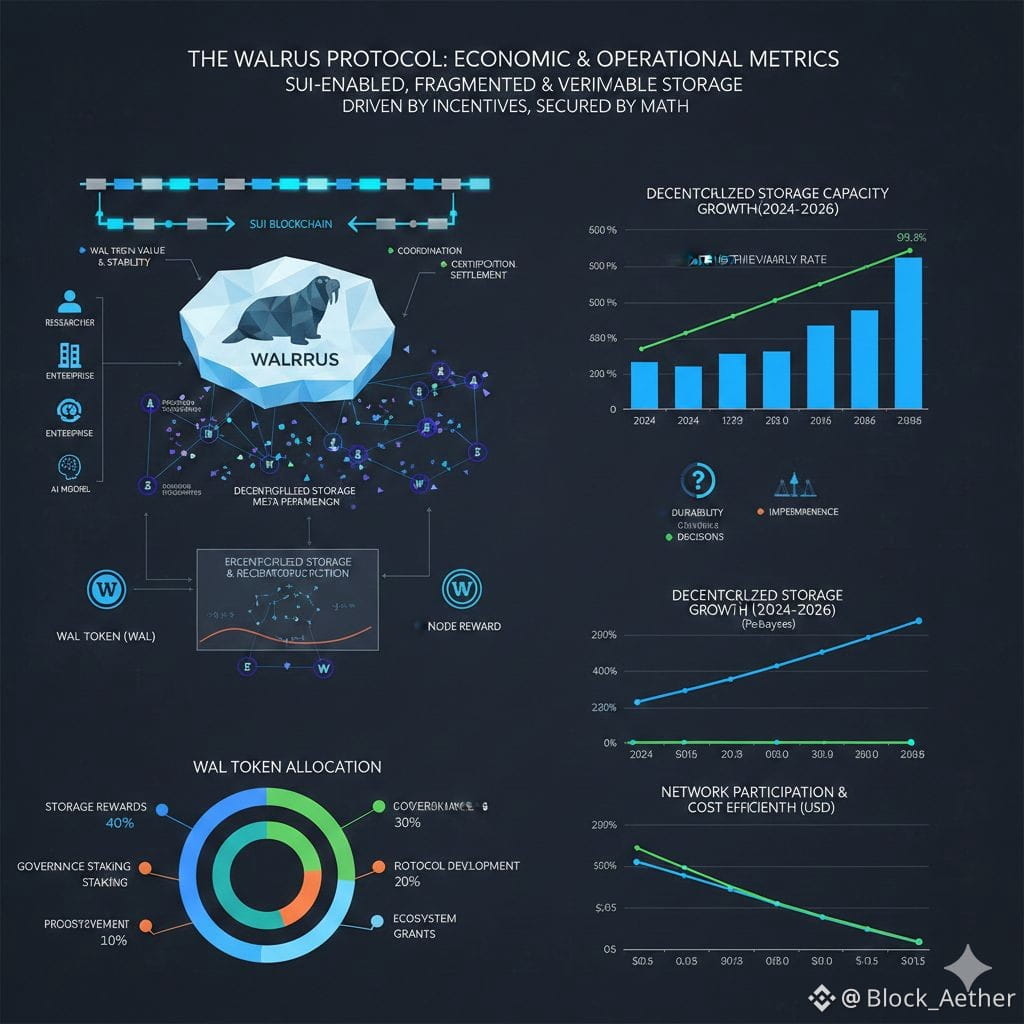

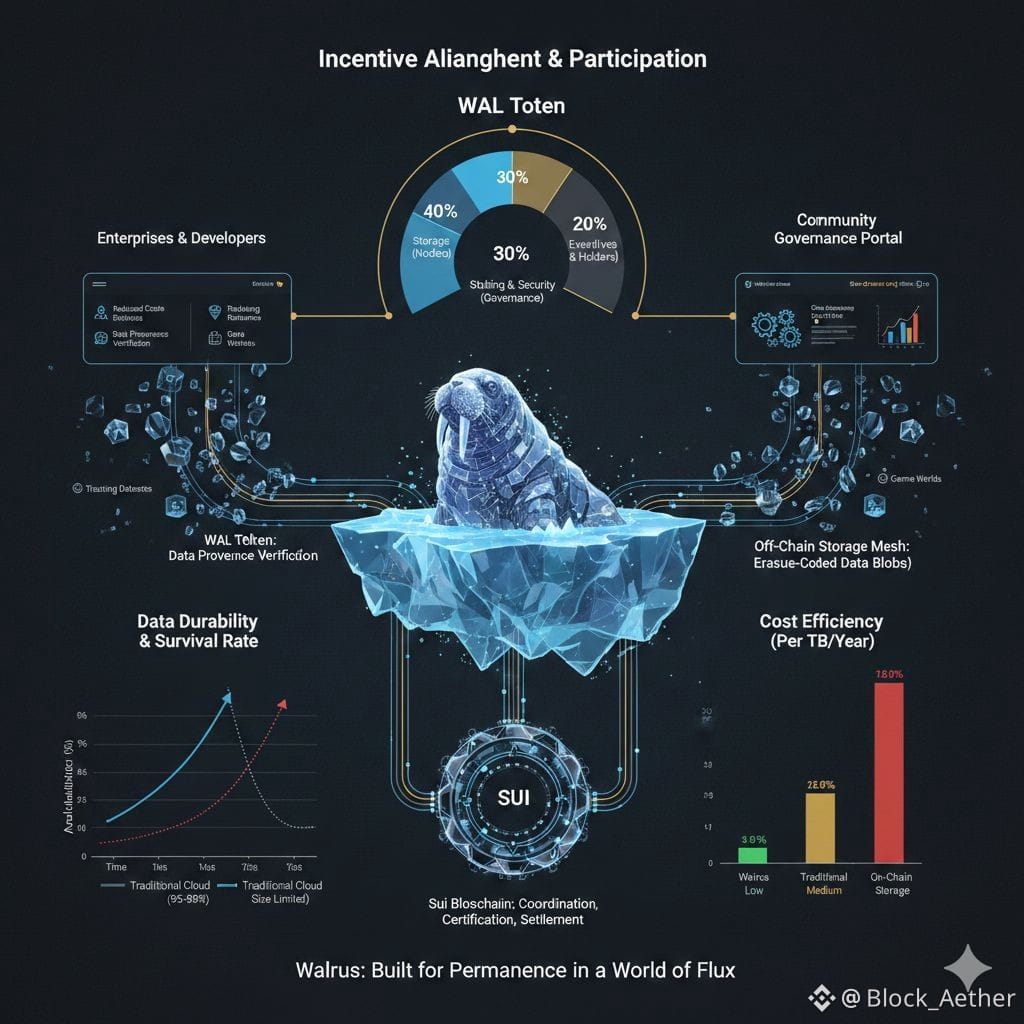

But storage alone is never just storage. Every byte lives inside an incentive structure. Walrus introduces WAL, its native token, not as a speculative flourish but as connective tissue. WAL pays for storage. WAL rewards the nodes that hold fragments. WAL gives its holders a voice in how the protocol evolves. This matters because decentralized systems fail most often not because of bad code, but because incentives drift. If storing data becomes unprofitable, nodes leave. If governance becomes opaque, trust erodes. WAL is meant to keep those forces aligned over time, even as the network grows and conditions change.

What makes this interesting is not the token itself, but what it reveals about the psychology of decentralized infrastructure. Walrus assumes that participants are rational but not altruistic. It doesn’t ask them to care about permanence or freedom or censorship resistance. It asks them to respond to clear, sustained economic signals. If you store data reliably, you are paid. If you stake and help secure the network, you earn influence. Ideology is optional. Participation is mechanical.

This design philosophy runs deeper than economics. Walrus deliberately keeps the blockchain lightweight. Sui is used to coordinate, certify, and settle, not to carry the data itself. The chain tracks what exists, who paid for it, and whether it is still available. The heavy lifting happens off-chain, across a shifting mesh of storage nodes. This separation is crucial. It preserves the blockchain’s speed while letting storage scale independently. It also creates a subtle but powerful abstraction: the idea that availability can be proven without trust, that you can verify a dataset exists and is retrievable without downloading it or believing a provider’s promise.

This is where Walrus quietly becomes more than infrastructure. In a world shaped by artificial intelligence, data provenance is everything. Models are only as good as the data they consume. Enterprises want proof that a dataset hasn’t been tampered with. Researchers want assurance that results can be reproduced. Walrus turns storage into a verifiable claim. A dataset stored today can be referenced tomorrow, next year, or a decade from now, with cryptographic evidence that it has not changed. That changes how data can be shared, sold, and trusted.

And yet, permanence has a shadow. Storing data in a censorship-resistant system raises uncomfortable questions. What happens when the data should not exist forever? Who decides? Walrus, like many decentralized protocols, pushes these questions toward governance rather than enforcement. There is no central authority to delete a file. There are only rules, incentives, and collective decisions. This is not a flaw so much as a philosophical stance, but it comes with consequences. Decentralization reduces control, but it also diffuses responsibility. The protocol can enable memory at scale, but society still has to decide what deserves to be remembered.

The human tension is unmistakable. Enterprises look at Walrus and see reduced costs, resilience, and vendor independence. Governments see jurisdictional ambiguity. Developers see composability: datasets plugged directly into dApps, NFTs backed by immutable assets, AI models referencing training data that can be audited. Users see a token whose value fluctuates with markets they may not understand. These perspectives collide inside the same system, each pulling it toward a different future.

Walrus does not pretend to resolve these tensions. It simply builds a structure sturdy enough to hold them. Its technology is ambitious but restrained. Its language is technical, almost austere. There is no promise that it will “change everything.” There is only the suggestion that storage, long treated as a boring backend concern, might be one of the most consequential layers of the decentralized stack.

If Walrus succeeds, it will not be because it was loud. It will be because it was useful in the moments when usefulness mattered most: when a dataset had to survive beyond a company’s lifespan, when a digital asset needed to exist independently of its creator, when trust had to be proven rather than assumed. If it fails, it will likely fail quietly too, under the weight of economics, regulation, or simpler systems that trade ideals for convenience.

Either way, Walrus reveals something essential about where decentralized technology is headed. The future is not just about moving value without intermediaries. It is about storing memory without owners. About building systems that assume impermanence at the edges and durability at the core. Like its namesake beneath polar ice, Walrus moves slowly, carrying mass rather than speed, reshaping its environment not through spectacle but through pressure. And in a digital world drowning in data, that kind of force may be exactly what endures.