The deeper I went into Web3, the more I realized that blockchains alone cannot carry the weight of the future. For a long time, I treated chains as the ultimate infrastructure — the place where truth lives. But as I studied AI, digital worlds, and creator economies, one uncomfortable truth became clear to me: ledgers are not enough. They can verify ownership, but they cannot reliably store the vast oceans of data that modern digital systems depend on. That realization is what pulled me toward Walrus Protocol.

At first glance, Walrus looks like “just another storage network,” but that description misses its essence. What struck me early on is that Walrus is not trying to replace blockchains — it is trying to complete them. Traditional blockchains are exceptional at small, high-value data like transactions and smart contract states, yet they are terrible at handling large files such as videos, datasets, 3D assets, or AI training material. Walrus steps into this gap and asks a different question: what if storage itself could be programmable, verifiable, and economically secured in a decentralized way?

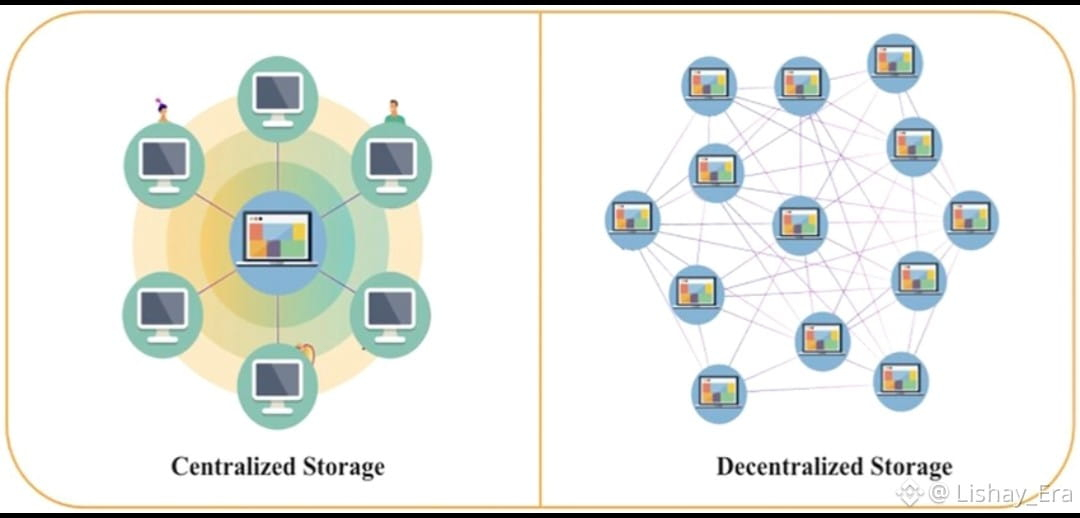

I began thinking about data the way economists think about land. In Web2, most of our digital land is leased from corporations. We build on it, enrich it, and depend on it — yet we never truly own it. Walrus reframes data as an economic asset rather than a technical byproduct. Instead of scattering files across fragile centralized clouds, Walrus treats data as something that deserves durability, ownership guarantees, and collective security.

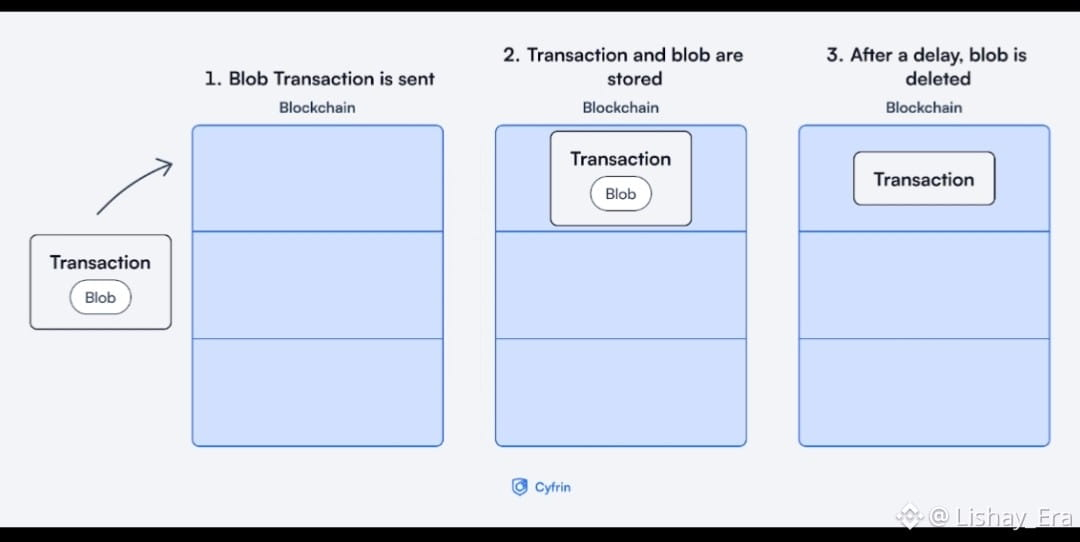

Technically, what fascinated me most was Walrus’s use of erasure coding — often described as “Red Stuff.” Instead of fully replicating every file across every node (which is inefficient and slow), Walrus splits data into encoded fragments that can be reconstructed even if parts of the network go offline. To me, this feels less like storage and more like digital insurance: your data survives not because one server is honest, but because the system itself is mathematically resilient.

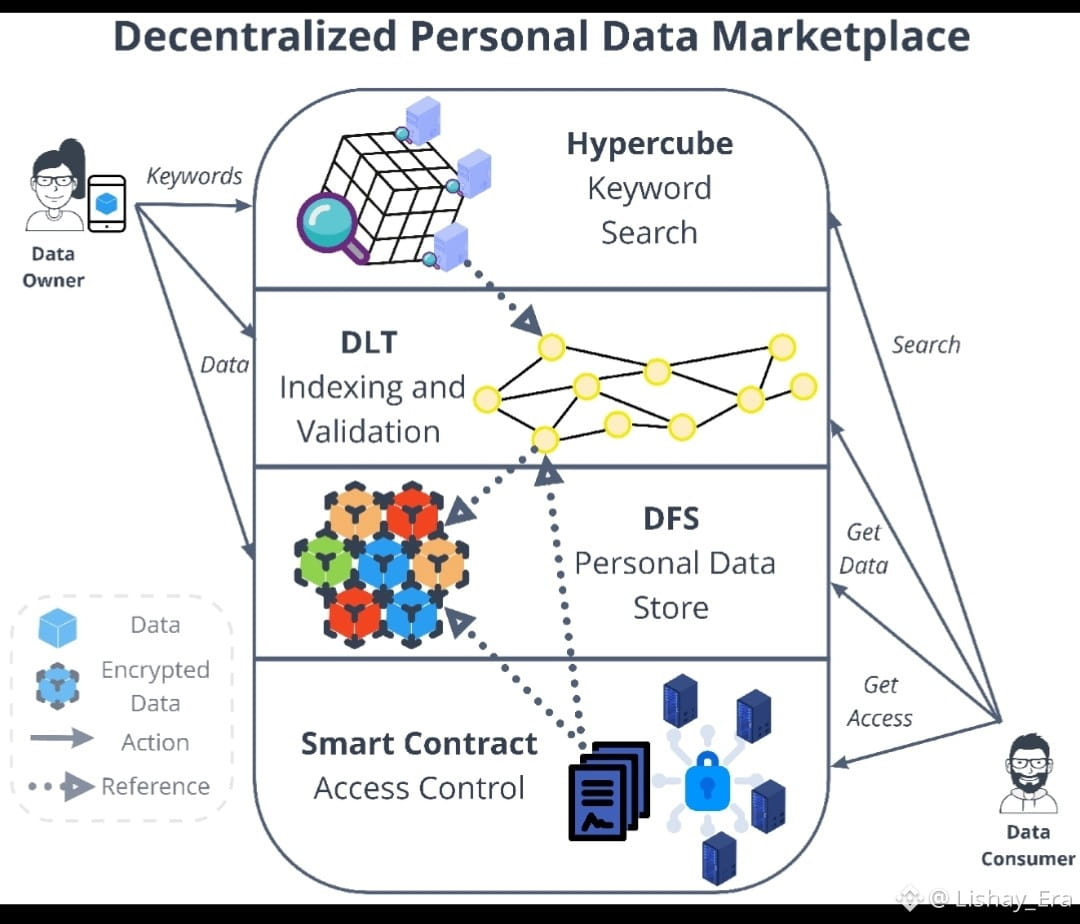

Another layer that made Walrus compelling is its integration with Sui’s object-centric model. Rather than treating data as floating files, Walrus links blobs to programmable objects on-chain. This means storage is not just a passive warehouse; it becomes part of an interactive digital ecosystem. When I realized this, I started seeing Walrus as a memory layer for decentralized worlds — a shared archive that anyone can build upon without asking permission.

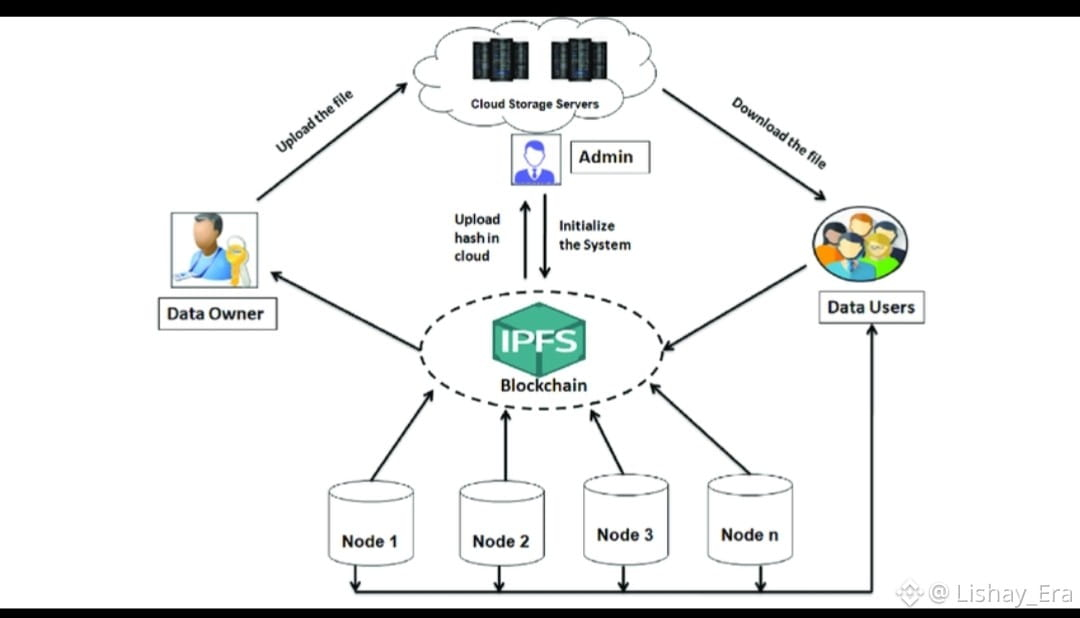

What separates Walrus from older decentralized storage systems like IPFS is this idea of programmability. IPFS is excellent at content addressing, but it struggles with guarantees about persistence and incentives. Walrus, by contrast, introduces economic coordination: storage nodes are rewarded for keeping data available across epochs, while proofs ensure that commitments are actually honored. It feels engineered rather than improvised.

As I connected these ideas, I began imagining AI agents operating in a Walrus-powered world. Autonomous systems need reliable data — not fleeting links that disappear when a server shuts down or a startup pivots. Walrus provides exactly that: a durable substrate where datasets, models, and digital artifacts can live long enough to be useful to machines and humans alike.

Importantly, WAL in this framework is not a trading instrument; it is infrastructure. Its role is to align incentives so that storage remains decentralized, censorship-resistant, and trustworthy. I found this refreshing because it shifts the conversation from speculation to utility — from price charts to system design.

I also appreciated how Walrus thinks about scalability. Instead of chasing raw throughput alone, it focuses on efficient data distribution. Large files are broken into shards that travel across the network intelligently, reducing redundancy while maintaining availability. This is crucial if we expect decentralized systems to host the rich media that future digital worlds will demand.

Over time, I began seeing Walrus as more than a protocol — it is a philosophy about how the internet should work. Data should not vanish when a company collapses. Creators should not lose their work because a platform changed policies. Knowledge should not be locked behind corporate gates. Walrus encodes these values directly into its architecture.

When paired with interactive chains like Vanar, the picture becomes even clearer. Vanar can power living digital objects, while Walrus preserves their history, media, and context. Together, they resemble a brain: Vanar as the nervous system, Walrus as long-term memory. Neither works fully without the other.

This also reshaped how I think about ownership. Owning a token means little if the underlying data it references can disappear. True digital ownership requires a reliable storage layer — and that is exactly the problem Walrus is designed to solve.

From a creator’s perspective, Walrus is quietly revolutionary. Artists, game designers, and builders can publish rich content without fearing centralized takedowns. Their work can persist across time, applications, and ecosystems, anchored in a decentralized network rather than a single company’s database.

Looking ahead, I believe networks like Walrus will become foundational to AI-driven economies. As machines generate and consume more data than humans ever could, we need storage systems that are open, verifiable, and resilient. Walrus feels built for that future rather than reacting to it.

In the end, my journey with Walrus changed how I see the internet. I no longer think in terms of websites or platforms — I think in terms of layers: computation, identity, interaction, and memory. Walrus is the memory layer that makes everything else possible.

If blockchains taught us how to trust without intermediaries, Walrus is teaching us how to preserve that trust at scale. And for me, that is not just technology — it is the foundation of a fairer digital world.