I’ve spent enough time watching teams “add privacy later” to know how messy it gets in practice. The first version usually ships with transparent state because it’s easy to debug and easy to integrate. Then real users arrive, and suddenly every balance change, counterparty, and payment pattern becomes a permanent public record. At that point, the conversation stops being philosophical and turns into procurement and risk.

The core friction for institutions isn’t just “hide everything” versus “show everything.” It’s that they need confidentiality for day-to-day operations, but they also need a credible way to prove they followed rules when someone is allowed to ask. Public chains like Ethereum make auditability simple because the state is visible, but confidentiality becomes an overlay of off-chain agreements and selective data withholding. Privacy-first systems like Monero push hard toward default secrecy, but the very thing that makes them strong for personal privacy can make them awkward for formal audit trails. Zcash sits in a more nuanced place with shielded transfers and optional disclosure, but you still run into the broader challenge: how do you scale privacy from “transactions” to “systems,” where apps, access control, and policy checks all exist?

It’s like wanting a bank vault where the door is opaque to the street, but the vault can still produce a signed inventory report to an authorized auditor.

The angle that makes Dusk Foundation interesting is the idea of integrated privacy plus auditability as a first-class design goal, instead of a compromise bolted on at the edges. In a system like that, the chain doesn’t try to convince the world that every detail is correct by showing the details; it convinces the world by showing proofs about the details. Practically, that means the state can be represented by cryptographic commitments rather than raw balances and identities, and updates can be accepted only when accompanied by validity proofs. The network’s job becomes verifying proofs and maintaining a consistent state transition history, not broadcasting everyone’s financial life.

If you decompose what this requires, you end up with a few non-negotiable layers. At the consensus layer, you want predictable finality and strong fork resistance, because privacy systems often rely on uniqueness properties (for example, preventing the same “spend credential” from being used twice). The consensus selection has to support fast agreement on ordering and finality so that nullifiers or equivalent anti-double-spend markers remain globally consistent. At the state model layer, you need a ledger that stores commitments, anti-replay markers, and minimal metadata, while keeping sensitive fields off the public surface. That’s not just “encrypted data”; it’s a different notion of what the canonical state is. At the cryptographic flow layer, transactions are more like structured arguments: the sender proves they have authorization to move value or update a contract state, proves conservation rules (or whatever invariants apply), and proves policy constraints, while revealing only what must be revealed. Auditability then becomes selective disclosure: the ability to hand an authorized party a viewing capability (keys, proofs, or attestations) that can open up a specific slice of history without turning the whole network into a glass box.

This is where the comparison matters. Ethereum’s strength is composability in the open, but that openness is also its default leak: even if you hide identities, patterns leak through state and timing, and contracts often demand visibility to be trustless. Monero’s strength is making linkability hard by default, but that same default can limit fine-grained audit narratives that institutions are used to producing. Zcash provides a strong privacy foundation, but “auditability” is still a product decision that sits on top of cryptography, and programmability and operational constraints can shape what’s practical. An integrated approach tries to make “confidential by default, provable when needed” feel like a normal operating mode rather than an exception.

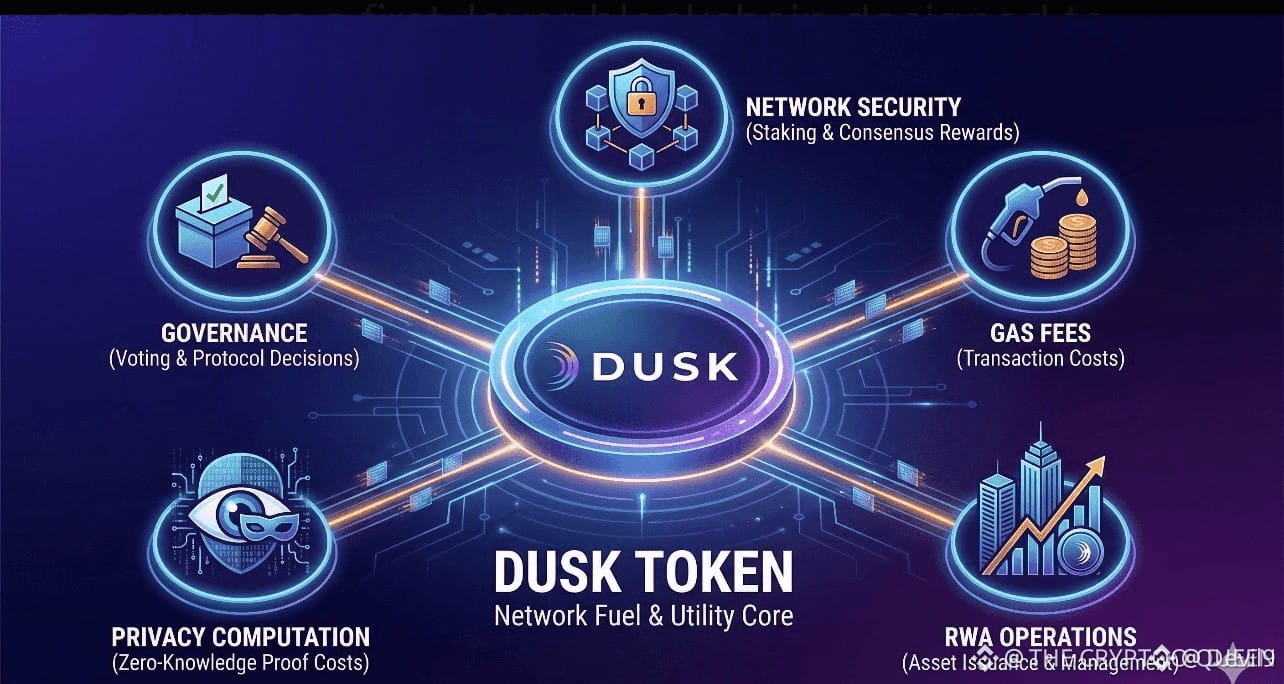

Economically, the utility story has to match that negotiation. Fees are not just payment for blockspace; they’re the ongoing price the market pays for proof verification, state maintenance, and network security. Staking, in a proof-of-stake setting, is the credibility bond: validators are paid for correct verification and ordering, and they risk penalties for behavior that threatens safety. Governance, if used carefully, is how parameters get renegotiated over time things like fee policy, verification limits, and upgrade cadence because privacy systems evolve, and you don’t want that evolution to feel arbitrary to builders who depend on it. The “price negotiation” here isn’t about targets; it’s about whether the fee market and staking incentives can sustainably pay for the heavier cryptographic workload without pushing users back to leaky shortcuts.

Uncertainty: hard part is less the math and more the long-run behavior whether real operators, real apps, and real compliance demands keep the privacy-and-audit balance stable under stress and upgrades.

From a builder perspective, the benefit is clarity: you can design applications assuming confidentiality is native, while still having a credible path to explain and prove what happened when the right party asks. I’m curious how you see the tradeoff does “selective auditability” feel like the missing middle ground between Ethereum-style transparency and Monero-style opacity?