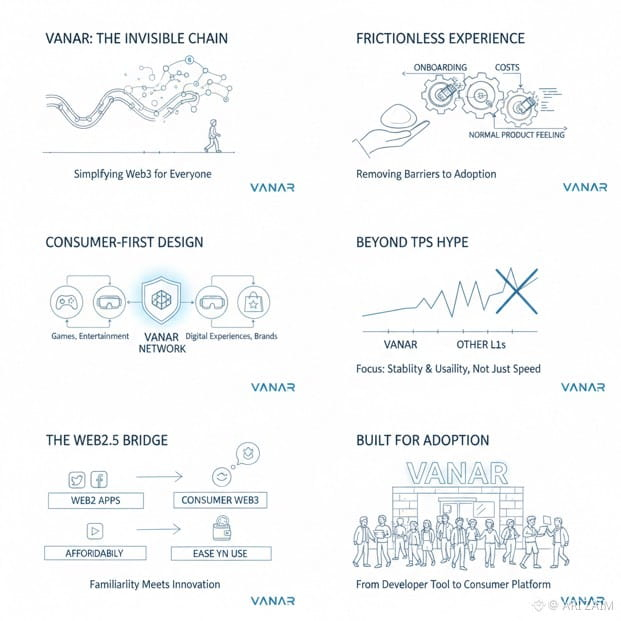

Vanar, to me, reads like a team that is trying to build a chain for people who don’t want to think about chains at all. That sounds simple, but it’s actually one of the hardest directions in this space, because “real-world adoption” is not a slogan you can force into existence with partnerships and hype; it’s something you earn by removing friction again and again until the product feels normal.

The way Vanar talks about itself makes it clear they’re not chasing the usual L1 bragging contest of who can print the biggest TPS number on a landing page. They’re trying to design a network that makes sense for consumer products—things like games, entertainment, digital experiences, and brand activations—where you can’t afford a clunky onboarding flow, unpredictable costs, or a user experience that constantly reminds people they’re using crypto. If you’ve ever watched a mainstream user bounce off Web3 because of fees, wallet confusion, or weird transaction timing, you can see why Vanar keeps leaning into “built from the ground up for adoption.” It’s basically an admission that the average L1 experience still feels like a developer tool, not a consumer platform.

The way Vanar talks about itself makes it clear they’re not chasing the usual L1 bragging contest of who can print the biggest TPS number on a landing page. They’re trying to design a network that makes sense for consumer products—things like games, entertainment, digital experiences, and brand activations—where you can’t afford a clunky onboarding flow, unpredictable costs, or a user experience that constantly reminds people they’re using crypto. If you’ve ever watched a mainstream user bounce off Web3 because of fees, wallet confusion, or weird transaction timing, you can see why Vanar keeps leaning into “built from the ground up for adoption.” It’s basically an admission that the average L1 experience still feels like a developer tool, not a consumer platform.

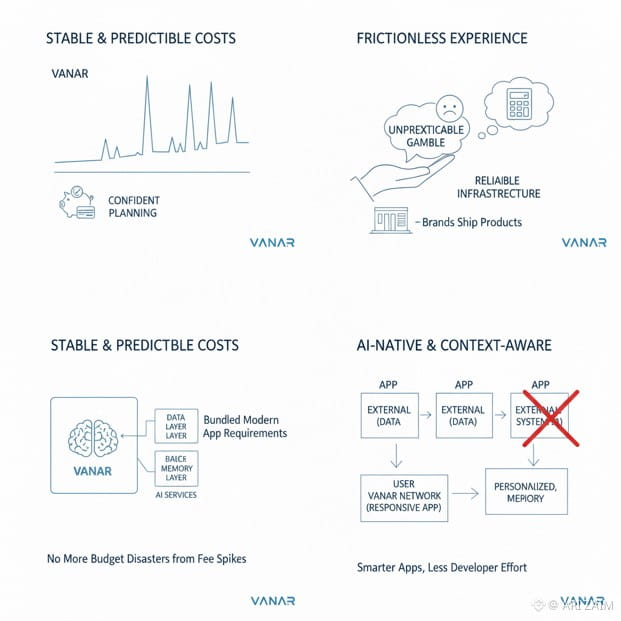

What stands out in their approach is the idea that costs should feel stable and predictable instead of swinging around with market conditions. When fees jump, consumer apps don’t just become more expensive; they become unreliable and hard to plan around. The moment a product manager can’t confidently say “a user action will cost roughly this much,” the project stops behaving like infrastructure and starts behaving like a gamble. Vanar’s attempt to anchor fees in a more stable frame of reference is, at least conceptually, one of the more practical choices you can make if you want brands to ship products on your network without worrying that a random market spike will turn their user acquisition campaign into a budget disaster.

Another thing you can feel in Vanar’s messaging is that they’re trying to bundle more of the “modern app requirements” into the base experience, instead of forcing builders to glue together a dozen external systems just to make an application feel smart and responsive. That’s where the AI-native narrative comes in. A lot of projects throw “AI” onto the front of whatever they’re building, but the only version of AI that matters for a blockchain is the version that becomes useful for developers—meaning it helps them store context, retrieve it, understand it, and act on it in a way that makes applications feel more personal, more responsive, and less brittle. Vanar is clearly trying to sell the idea that the chain should be able to support that kind of “context-aware” behavior without every team reinventing the same data and memory layer on top of a ledger.

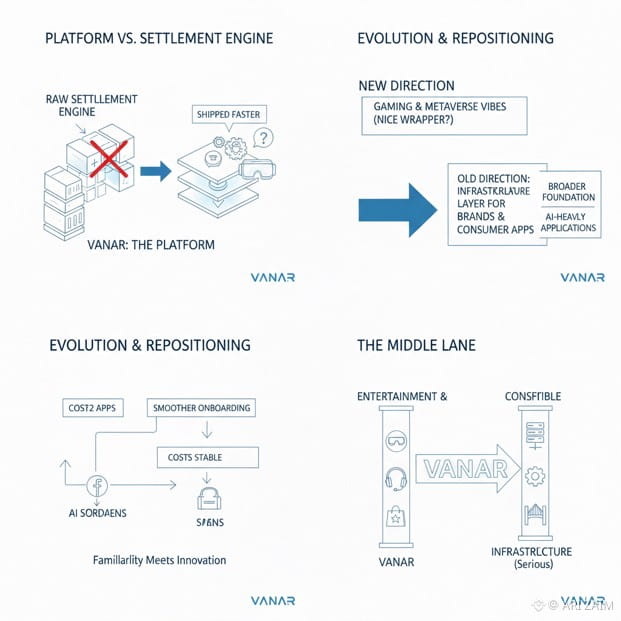

If you step back, Vanar’s “behind the scenes” work seems to be about making the chain behave less like a raw settlement engine and more like a platform. That’s an ambitious promise, and it’s also where the risk lives: building a platform identity is only meaningful if developers can actually feel the advantage. It’s not enough to say “we have a semantic layer” or “we do reasoning,” because the market has become numb to architecture diagrams. What will make Vanar real is if builders can point to it and say, “we shipped faster,” “our costs didn’t blow up,” “our onboarding is smoother,” or “we built something that would have been painful on another chain.” Those are the kinds of results that turn marketing words into credibility.

The project also carries the weight of its own evolution. When a team repositions, expands scope, and tries to become a broader foundation, the market naturally asks whether it’s genuine progress or just a nicer wrapper around the same story. Vanar seems aware of that pressure, because their direction has widened: it isn’t only about gaming and metaverse vibes anymore; it’s increasingly about being the infrastructure layer that brands and consumer applications can rely on, while also leaning into the idea that AI-heavy applications will need a different kind of chain experience than the one we’ve normalized over the last few years. In a way, they’re trying to occupy a middle lane: still friendly to entertainment and consumer culture, but serious enough to be “infrastructure.”

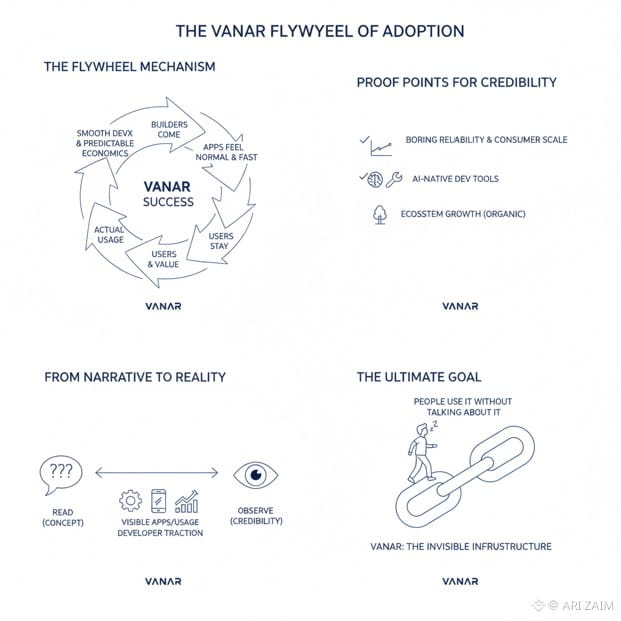

Where I think Vanar will be judged is not by how many verticals they list, but by whether they can create a flywheel. A flywheel looks like this: builders come because the developer experience is smooth and the economics are predictable, users stay because the apps feel normal and fast, and the network becomes valuable because actual usage—not just speculation—keeps showing up every day. Vanar’s success is basically the success of that loop. Without it, the project feels like a well-presented concept. With it, it becomes the kind of chain that people use without talking about it.

So when you ask “what’s next,” I don’t think the most important thing is a single big announcement, because adoption rarely comes from one moment. The next meaningful chapter is proving that the chain can support real consumer scale with boring reliability, proving that the AI-native story translates into tools that developers genuinely want, and proving that the ecosystem is growing in a way that doesn’t depend on constant incentives to stay alive. If Vanar starts stacking those proofs—steady shipping, visible apps, repeat usage, and developer traction—then the narrative will stop being something you read and start being something you can observe.

So when you ask “what’s next,” I don’t think the most important thing is a single big announcement, because adoption rarely comes from one moment. The next meaningful chapter is proving that the chain can support real consumer scale with boring reliability, proving that the AI-native story translates into tools that developers genuinely want, and proving that the ecosystem is growing in a way that doesn’t depend on constant incentives to stay alive. If Vanar starts stacking those proofs—steady shipping, visible apps, repeat usage, and developer traction—then the narrative will stop being something you read and start being something you can observe.

Vanar is aiming at a practical truth: mainstream users don’t care about decentralization debates or consensus acronyms; they care that things work, feel simple, and don’t surprise them. If Vanar can make the chain experience fade into the background while giving developers a real advantage in cost predictability and context-aware application building, then it earns the right to talk about bringing the next wave of consumers onchain. If it can’t, then it risks becoming another project that sounds ready for mass adoption but never crosses the line from “promise” to “proof.”