@Vanar Vanar is an L1 blockchain designed from the ground up to make sense for real-world adoption, not just for people who enjoy protocols as a hobby. Its own positioning is blunt about the direction: an “AI-powered blockchain” aimed at onchain finance and tokenized real-world infrastructure, built as a base layer beneath higher “intelligence” layers like semantic memory and reasoning.That framing matters, because it explains why a talent program is not a side quest here. If you actually believe the next era of apps is part software and part intelligence, you can’t treat builders as an afterthought. You have to grow them deliberately, in the same way you would grow validator capacity or developer tooling.

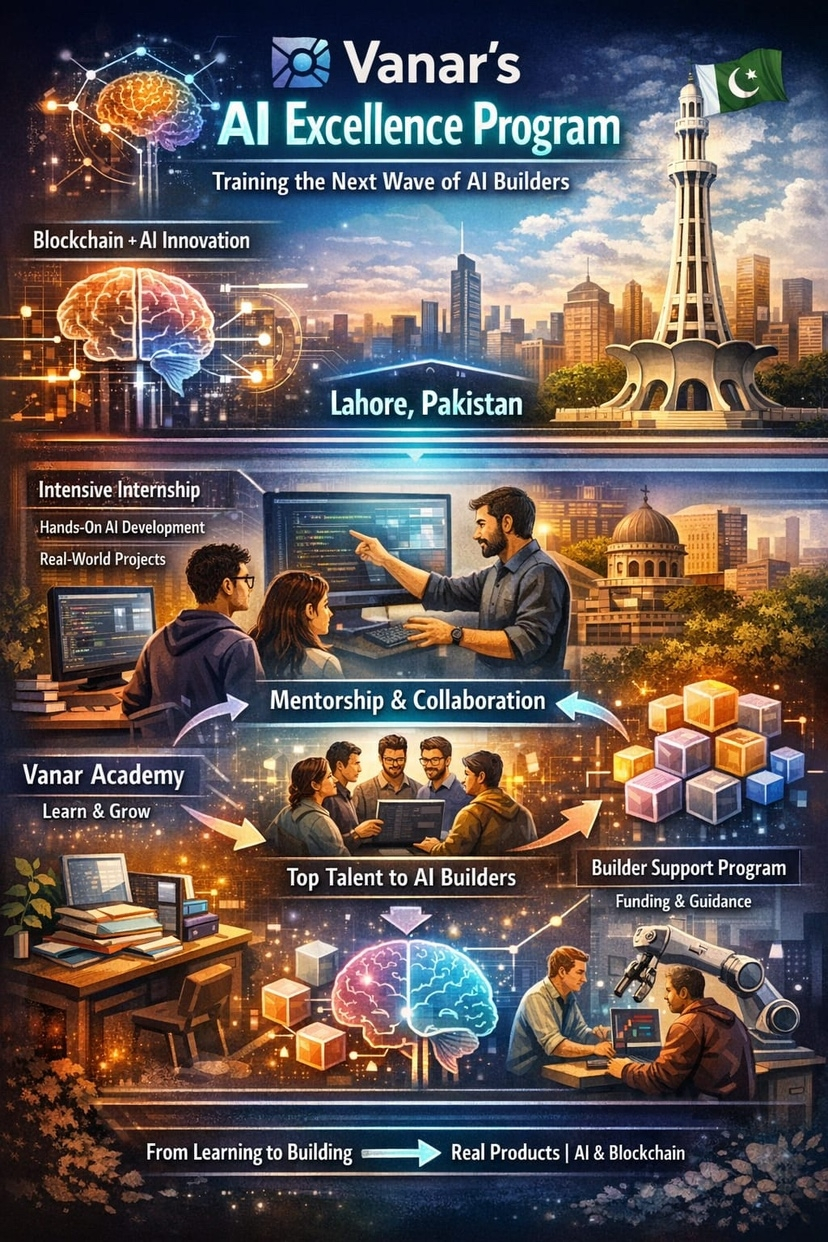

That is the context in which Vanar’s AI Excellence Program lands: as a practical attempt to train “the next wave of AI-native builders,” in Pakistan, with an internship structure rather than a loose community challenge. The program has been described publicly as a three-month, on-site experience in Lahore, with a tone that leans closer to product work than classroom theory—“real products, not playgrounds”—and with an explicit claim that top performers can convert into roles rather than leaving with a certificate.

Even if you take it with some skepticism, it still shows their intent: they’re not chasing attention, they’re building a pipeline.

This is trending right now for reasons that aren’t about hype, but about timing. From 2024 to 2026, AI shifted from a “nice extra” to something people actually run their work on. And the biggest problem quickly became people, not technology: teams can’t easily find builders who can put models into real products, judge data when things get messy, and write code that still works when users act in unexpected ways. In parallel, Web3 is going through its own maturity test—less tolerance for experiments that don’t serve anyone, more pressure to produce tools that survive compliance, latency, and user trust. Vanar is clearly trying to stand in the overlap: AI × Web3, but with a real-world orientation. When that overlap becomes your identity, training stops being philanthropy and starts being infrastructure.

The interesting part is what an “excellence program” can realistically mean in practice. Most initiatives fail because they confuse content with capability. A few lectures and a demo day create confidence on LinkedIn, but they don’t create the muscle memory you need when the data is messy, the model is wrong in subtle ways, and users blame the product anyway. Vanar’s public language pushes toward a more intense model: small cohorts, on-site collaboration, and work that resembles the ambiguity of real product development. The “Vanar Communities” update claiming 15 interns were selected from universities across the country points to cohort design that is intentionally narrow rather than mass-market. That can be a strength, because deep training doesn’t scale cleanly. It’s closer to apprenticeship than education.

There’s also a regional angle that’s easy to miss if you only look at the crypto side. Pakistan has a large, young technical population, and in recent years it has produced strong software talent—yet many of the best roles, mentorship loops, and startup resources still concentrate elsewhere. A program that is physically rooted (on-site, Lahore) is making a bet: that proximity and daily iteration still matter, even in a remote-first world.In AI work specifically, proximity can compress learning cycles because the fastest lessons usually come from code reviews, debugging sessions, and uncomfortable conversations about why a model failed. You can do that remotely, but it’s harder to sustain as a cultural habit when you’re building from scratch.

Vanar also appears to be building a broader learning and builder funnel around the internship, which is important because an excellence program is only the top of the pyramid. Their Academy is positioned as a free learning platform with guided modules, tutorials, projects, and community support—more “entry and ramp” than “elite cohort.” On the developer side, Vanar advertises a builder’s program that supports teams working on product ideas with guidance and ecosystem exposure. Put together, you can see a pattern: self-serve learning (Academy), structured support (builder program), and then a selective on-site cohort (AI Excellence Program). That kind of funnel is how ecosystems stop relying on luck.

What counts as “real progress” here is not a slogan about training. It’s whether the surrounding system exists to turn trained people into builders who stay. One credible data point is that Vanar has already run structured programs in Pakistan that connect learning to product outcomes.

A report dated July 31, 2025 says Vanar ran a Web3 Leaders Fellowship with support from Google Cloud. It ended with eight products. The program also offered up to $25,000 in Google Cloud credits and a separate Vanar grant that could reach $25,000, plus hands-on technical sessions.

This matters because it shows they’ve done this kind of program before. They’ve managed a cohort, worked with a partner, and produced demo results. The AI Excellence Program looks like a similar setup, but focused more on AI talent than on startup founders.

.

Another kind of progress is narrative discipline. Vanar’s own stack description stresses that “data flows up through each layer,” positioning the base chain as the foundation for higher-order intelligence features.

If the platform depends on AI-first apps, then you need builders who understand more than just models. They also need to know how data is stored, checked, and turned into features people actually use.

This is where most developers struggle.They might know how to train a model, or how to build on-chain code, but turning that into a real AI product people trust day to day is a different skill entirely. The training program, if done well, is essentially a bridge between those worlds.

Still, there’s a hard truth: training programs can accidentally produce confident generalists rather than reliable specialists. The way you avoid that is by forcing contact with constraints.

With AI, you’re always working within boundaries: you don’t have unlimited compute, the data isn’t perfect, labels can be confusing, privacy has to be protected, and users usually prefer something that works the same way every time over something that’s impressive once. In Web3, constraints look like: irreversible actions, adversarial environments, key management mistakes, and public scrutiny when something breaks. A serious excellence program would teach people to treat constraints as design inputs, not obstacles. The visible emphasis on “real products” is promising, but the proof is always in what participants ship and what they learn when it doesn’t work the first time.

The reason this could matter beyond Vanar is that ecosystems have started to realize something basic: you can’t outsource your future to the internet. If you want builders who think in your primitives—your tooling, your data assumptions, your product standards—you have to invest in them early, and you have to give them pressure-tested environments to grow. That’s especially true in places like Pakistan, where the raw talent is present but the structured pathways into frontier work are still emerging.

If Vanar executes, the best outcome is not a press release. It’s a small but compounding shift: a cohort of builders who can move from experimentation to production, who can explain tradeoffs in plain language, and who can build AI systems that behave responsibly when users are confused, stressed, or financially exposed. And if Vanar doesn’t execute, the program still teaches a lesson the industry keeps relearning: incentives and branding don’t replace mentorship, and “AI × Web3” doesn’t become real until people can ship it, maintain it, and defend it under real usage. Either way, the AI Excellence Program is a useful signal—because it shows Vanar is trying to compete on capacity, not just on claims.