People talk about storage speed as if it’s a benchmark contest. Faster uploads. Faster reads. Bigger numbers on a chart. In practice, speed matters for a quieter reason: it determines whether teams trust the system enough to keep using it.

I’ve watched teams abandon decentralized storage without ever saying they did. No blog post. No angry thread. Just a silent reroute to centralized infrastructure after the third time something felt off. An upload that stalled. A retrieval that worked yesterday but not today. A repair that triggered a bandwidth spike at the wrong moment.

That’s not a technical failure in isolation. It’s a retention failure.

From an operator’s perspective, “fast” is not a single dimension. It’s a bundle of behaviors that decide whether storage feels like infrastructure or like a science project. How long does an upload block a user flow? How predictable are reads under load? And when nodes churn because they always do — does recovery look routine or catastrophic?

Walrus is interesting because it is explicitly designed around those questions, not around the cheapest possible storage cost or the cleanest theoretical model.

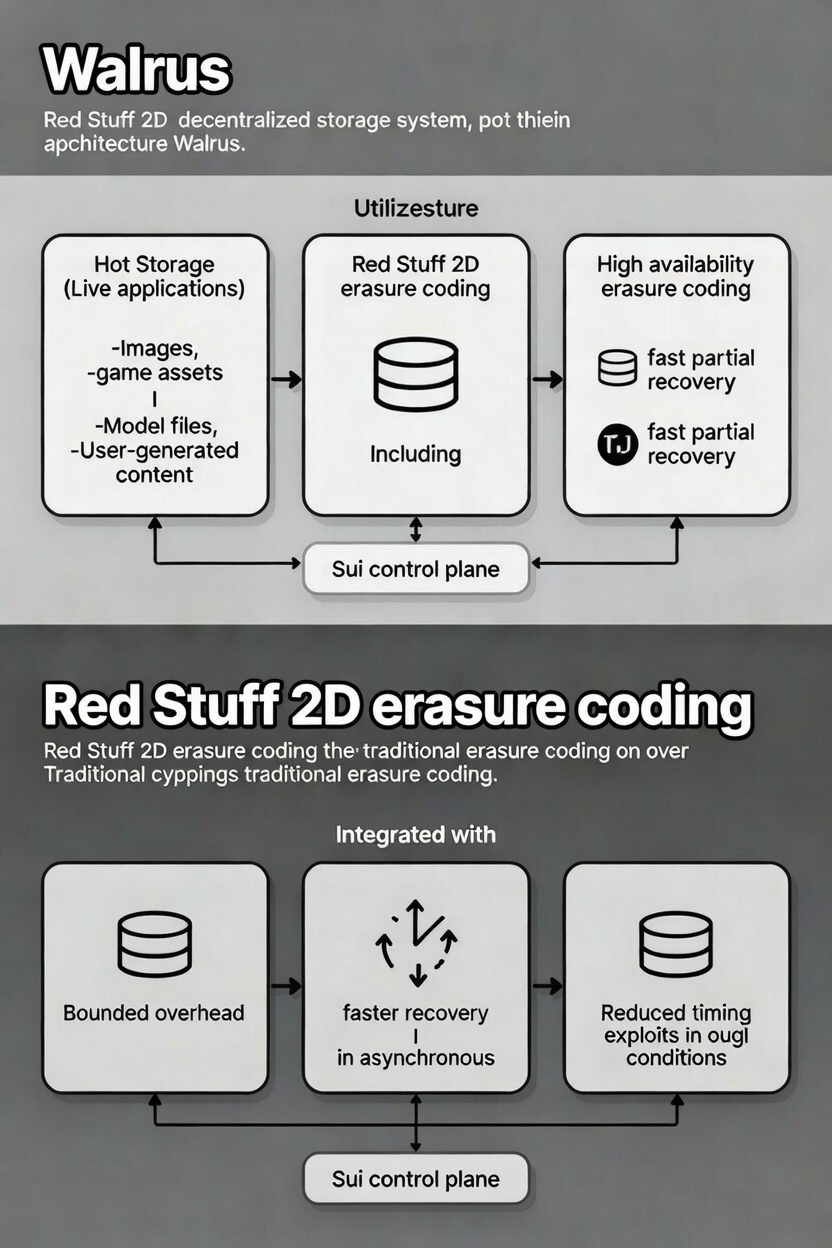

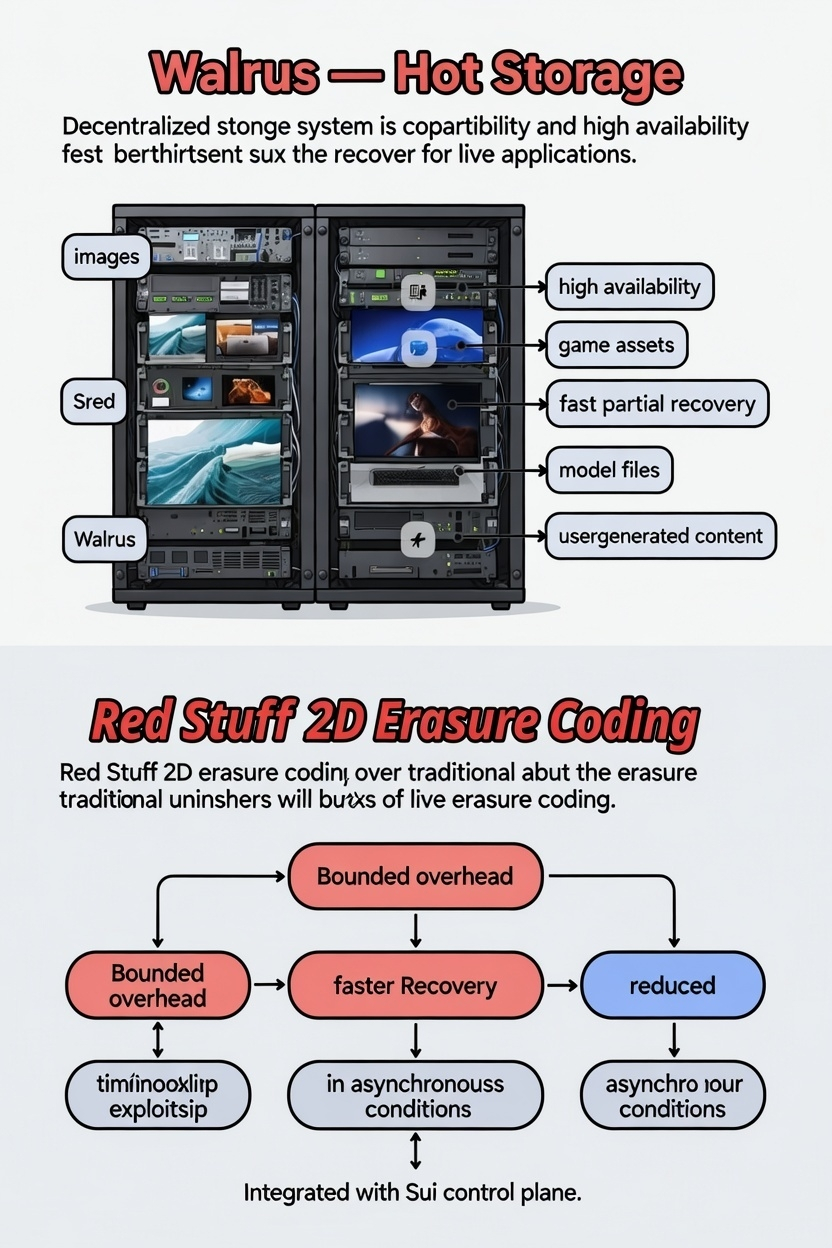

At a high level, Walrus separates concerns. Coordination and incentives live on Sui. Data lives off-chain, encoded and distributed across many independent storage nodes. That choice alone signals a bias toward operational clarity. You don’t need a bespoke blockchain just to move bytes around, but you do need a reliable way to coordinate who is responsible for what, and when.

The more consequential design choice sits in the data plane. Walrus uses a two-dimensional erasure coding scheme called Red Stuff. The intent is not novelty. It’s damage control.

Full replication is easy to reason about, but it scales poorly. Traditional erasure coding reduces storage overhead, but it often turns node churn into a repair storm. In real networks, that repair traffic competes with user traffic, which is exactly when you don’t want surprises.

Red Stuff aims for a middle path. Walrus targets roughly a 4.5× storage overhead higher than minimal erasure coding, lower than heavy replication and pairs it with recovery behavior where bandwidth scales with what was lost, not with the total size of the blob. That distinction doesn’t show up in a marketing slide. It shows up when a few nodes disappear and the system doesn’t flinch.

Importantly, the design assumes asynchronous conditions. Nodes are slow. Messages arrive late. Some participants behave strategically. Storage challenges are structured to reduce the ability to “look honest” by exploiting timing gaps. This doesn’t make the system immune to failure. It makes certain classes of failure harder to hide and easier to reason about.

Performance numbers are where design intent either starts to look plausible or collapses.

In Walrus’s testnet evaluation, the network consisted of 100+ independently operated storage nodes across more than a dozen countries. That matters. Latency in a homogeneous cluster is not the same thing as latency across real geography.

Client-side measurements showed read latency below ~15 seconds for blobs under 20 MB, rising toward ~30 seconds for blobs around 130 MB. Writes stayed under ~25 seconds for small blobs, then increased roughly linearly as network transfer dominated. This is not “instant.” It is predictable.

The paper is explicit about fixed costs. Roughly six seconds of write latency for small blobs comes from metadata handling and publishing availability information via the control plane. That overhead is not free, and it doesn’t disappear with better networking. But it is stable. Operators can plan around stable costs. They struggle with erratic ones.

Throughput adds another layer. Single-client write throughput plateaued around 18 MB/s. Reads scaled more naturally with blob size. This tells you where the system bends today. Not at raw bandwidth limits, but at coordination and multi-party interaction costs. That’s a useful signal. It tells you where future optimization effort will likely concentrate.

Recovery behavior is where many storage designs look good on paper and painful in practice. Classic erasure coding schemes often require moving data volumes comparable to the original file during reconstruction. That’s tolerable when churn is rare. It’s brutal when churn is normal.

Walrus’s two-dimensional structure is designed so repairs resemble patching missing fragments rather than rebuilding entire blobs. Again, this is not a guarantee. It’s a bias. A bias toward making recovery boring and proportional instead of dramatic and expensive.

Comparisons to other systems are unavoidable but should stay mechanical. With Filecoin, fast retrieval typically depends on storage providers maintaining hot copies, which are not inherently incentivized unless explicitly paid for. With IPFS, availability often depends on pinning discipline and gateway behavior. These are not flaws. They are tradeoffs. And tradeoffs show up in user behavior.

So how should Walrus be evaluated by someone who cares about execution, not slogans?

Run three tests. Measure upload time end-to-end, including encoding and confirmation. Measure cold retrievals under realistic load. Then simulate partial data loss and observe recovery bandwidth and time. Those three numbers tell you far more than a headline throughput claim.

The investment case, if there is one, does not hinge on Walrus being the fastest network in the world. It hinges on whether it makes decentralized storage feel dependable enough that teams stop quietly defecting. Retention is the signal. Repeated uploads. Repeated reads. Fewer late-night messages about “weird storage behavior.”

This doesn’t guarantee success. But it changes what failure looks like. And in infrastructure, changing failure modes is often the difference between a system that survives contact with reality and one that doesn’t.