Most blockchains feel like they are trying to be understood.

They explain themselves through numbers, architectures, and comparisons. They compete loudly, measuring success by how convincingly they can argue their design choices against other systems. The industry has become very good at talking to itself.

Vanar doesn’t read like it’s participating in that conversation.

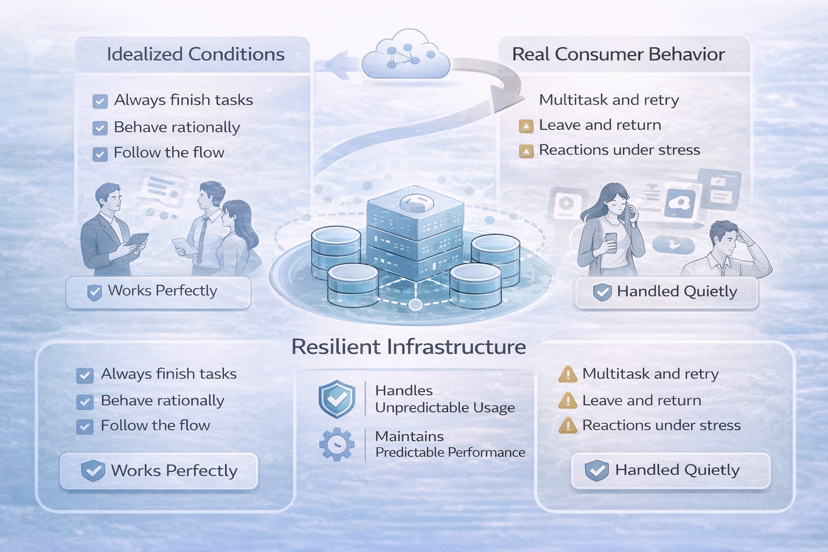

Viewed closely, it feels less like a blockchain designed to impress peers and more like infrastructure designed to tolerate reality. Not ideal conditions. Not rational users. But actual consumer behavior, where people act inconsistently, abandon flows, retry actions without context, and expect systems to recover without explanation.

That shift in assumptions changes everything.

Most systems fail not because they lack innovation, but because they expect users to behave correctly. Vanar appears to start from the opposite premise: users will behave unpredictably, and the system must absorb that quietly.

Building for Failure Before It Happens

Consumer-facing environments are inherently chaotic. People move fast. They multitask. They leave screens open, return later, and expect continuity. They don’t care about how consensus works or why a transaction stalled. They only notice when something feels slow, confusing, or broken.

Infrastructure that survives here isn’t elegant on paper. It’s resilient in practice.

Vanar’s design choices consistently point in that direction. Latency is treated as a hard requirement rather than a bragging metric. Errors don’t propagate dramatically across the system. Recovery paths are present, not as edge cases, but as expected behavior.

This isn’t the mindset of a protocol trying to win debates. It’s the mindset of a system that expects to be blamed when anything goes wrong.

From that angle, Vanar doesn’t try to be visible. It tries to be dependable.

What Real Usage Looks Like

Speculative activity leaves a recognizable trace. Sharp bursts of volume. Spikes driven by attention. Then silence. That pattern appears across many networks.

Vanar’s activity profile looks different.

Instead of volatility, there is rhythm. Repetition. Consistent interaction over time. Dense transaction flow that doesn’t disappear once interest fades. That doesn’t automatically mean millions of people are clicking buttons manually, but it does suggest something important: live systems interacting continuously.

Games, marketplaces, and application logic don’t generate that kind of signal unless they are embedded into experiences users return to regularly. These environments are unforgiving. Performance regressions aren’t tolerated. Fee unpredictability isn’t debated. If something feels unreliable, users simply stop engaging.

A chain that maintains steady interaction under these conditions isn’t demonstrating theoretical capacity. It’s demonstrating operational durability.

Predictability as a Design Constraint

One of the more revealing choices appears in how fees are treated.

In many networks, fees are framed as outcomes of market dynamics something to optimize, speculate on, or arbitrage. For consumer applications, that framing is actively harmful. Developers don’t want variability. They want boundaries. Users don’t want to calculate. They want to act.

Vanar’s approach suggests fees are treated as a constraint applications must be able to plan around. The aim isn’t just low cost, but stable cost. Pricing transactions in predictable dollar terms, even as token prices move, reduces cognitive overhead across the stack. It allows in-app economies to behave like systems rather than markets.

This choice isn’t philosophically pure. It requires managed components. It reflects intentional trade-offs in pricing and validation. But those trade-offs align closely with how real products are built and maintained.

Entertainment platforms optimize for consistency, uptime, and brand safety. From that perspective, these compromises don’t feel uncomfortable. They feel necessary.

The Value of Being Boring

There is also significance in what Vanar does not try to do.

There’s no visible urgency to frame itself as the future of everything. No rush to dominate narratives. The posture feels closer to traditional infrastructure: trust is expected to accumulate slowly by staying predictable.

Not breaking.

Not surprising users.

Not demanding adaptation.

In institutional systems, boring is often a compliment. It means things behave the same way day after day. Blocks arrive when expected. Fees behave consistently. Updates ship quietly because nothing went wrong.

If Vanar succeeds at what it appears designed to do, most users will never know its name. They’ll just notice that a game loads smoothly, a transaction confirms without stress, and nothing strange interrupts the experience.

In consumer technology, that is often what success actually looks like.

Treating Data as Context, Not Just History

Another subtle but important signal lies in how data appears to be approached.

Many blockchains are excellent at proving that something happened. They are reliable historical records. Far fewer are useful as memory layers that applications can reason with efficiently.

Vanar’s direction suggests an attempt to compress experience into smaller, verifiable units that applications can reference without dragging full historical context on-chain. The goal doesn’t feel novel. It feels practical.

Modern digital experiences don’t just generate transactions. They generate state. Games, brand environments, and marketplaces all depend on context that must be portable, auditable, and lightweight. If a chain can manage that context cleanly, it stops behaving like a ledger and starts behaving like infrastructure software applications rely on.

Function Over Symbolism

The same restraint appears in token design.

The token’s role seems functional rather than symbolic. Transactions, staking, coordination. Even the presence of an external standard version for interoperability suggests an assumption that users and liquidity will move across ecosystems without friction.

Systems that scale to mainstream usage often do so by becoming less visible, not more. Vanar appears aligned with that trajectory.

Whether this model is appealing depends on what one expects blockchains to be good at. If ideological purity is the priority, the approach may feel uncomfortable. If the goal is large-scale consumer interaction without friction, it starts to look rational.

Vanar doesn’t seem interested in changing how people think about blockchains.

It seems more interested in making sure people don’t have to think about them at all.