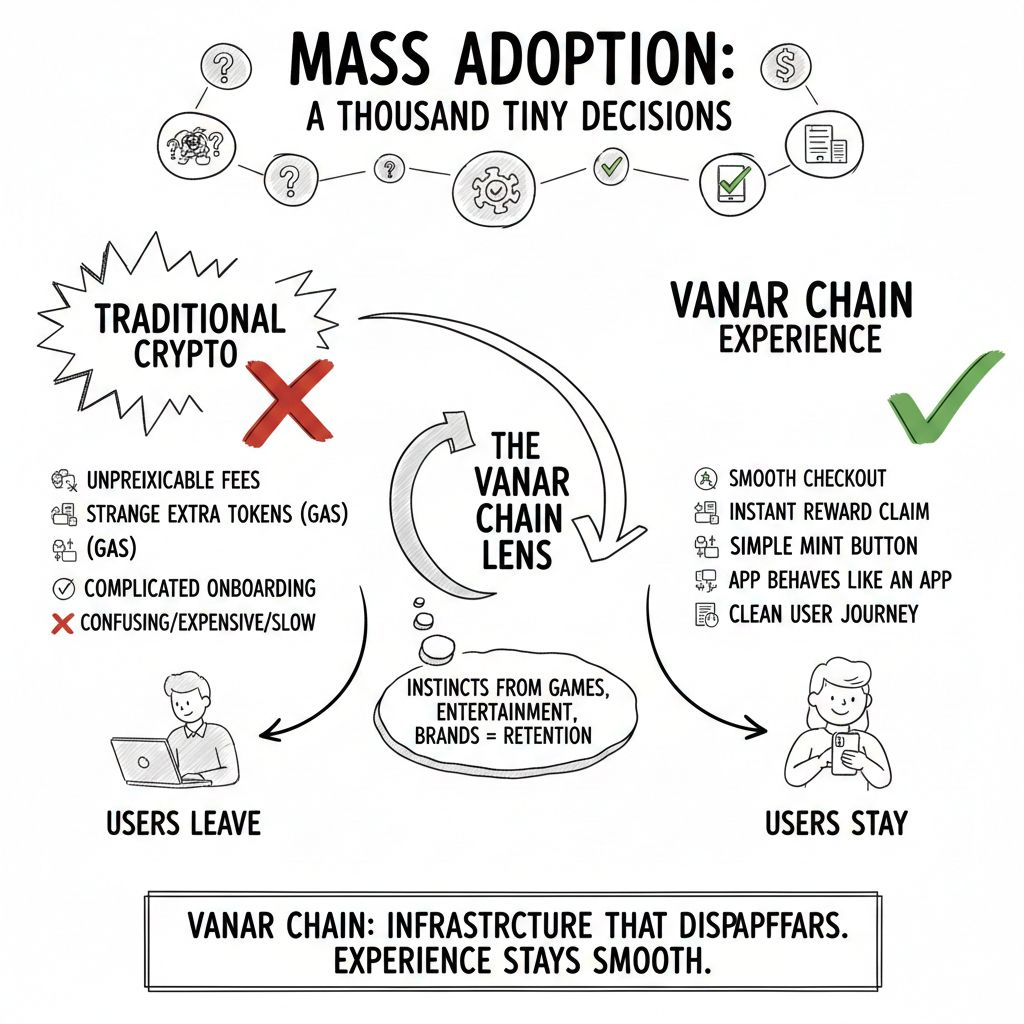

People talk about “mass adoption” like it’s a wave that suddenly hits. I think it’s more like a thousand tiny decisions where someone chooses not to leave. The checkout doesn’t hang. The reward claim feels instant. The mint button doesn’t look like a gamble. The app behaves like an app, not like a science project. That’s the lens I use for Vanar Chain. It isn’t trying to win a popularity contest with buzzwords. It’s trying to become the kind of infrastructure that disappears in the background while the experience stays smooth.

Vanar makes more sense when you remember where its instincts come from. A team that has worked with games, entertainment, and brands usually thinks in retention, not in ideology. In those worlds, you can’t lecture users into patience. If something feels confusing or expensive or slow, people simply close the tab and never come back. Crypto has often asked consumers to accept the opposite: unpredictable fees, strange extra tokens for gas, and onboarding steps that feel like paperwork. Vanar reads like a pushback against that. The goal seems to be building a chain where product teams can design a clean user journey without worrying that the network will change the rules halfway through.

The clearest signal is how Vanar approaches fees. In its documentation, the chain describes a fixed, tiered fee structure where common actions like transfers, swaps, NFT mints, staking, and bridging sit in the lowest tier, targeted at about the VANRY equivalent of 0.0005 dollars. That number is tiny, but the bigger point is the intent behind it. It’s not just about being cheap. It’s about being predictable. When you build consumer products, predictability is trust. If a creator wants to mint 1,000 items, they need to know the cost up front. If a game wants to distribute rewards every match, it needs the math to stay stable. If a brand wants to run a campaign, it can’t afford moments where a simple interaction suddenly costs enough to break the experience.

Fixed fees come with a real challenge, though: token volatility. If the price of the gas token moves, the network has to keep translating that into a fee level that still matches the intended user experience. Vanar’s docs describe handling this by regularly updating a validated market price for VANRY using multiple sources, so the fee targets can stay aligned with real market conditions. The whitepaper also describes a foundation-run process that calculates a market price and integrates it into the protocol so transaction charges can adapt over time. That approach won’t satisfy every purist, but it fits a product-first mindset. It’s basically saying: we care more about the user experience staying consistent than about pretending the network can run on autopilot without any calibration.

What I also like is that Vanar doesn’t pretend ultra-cheap transactions are automatically safe. The whitepaper talks about how extremely low fees can invite abuse, like block-filling with heavy transactions, and argues for charging more for larger, heavier operations to keep spam and denial-of-service style pressure economically unattractive. That’s a practical way to think. Cheap for normal people, expensive to break things. It’s not glamorous, but it’s the kind of thinking that keeps a consumer platform alive.

Vanar also makes a deliberate compatibility bet. The whitepaper states that it aims for full EVM compatibility and uses Geth, with the idea that what works on Ethereum should work on Vanar. I read that as another sign the project wants to reduce friction for builders. Most developers don’t want to relearn everything just to try a new chain. They want to ship. If the tooling and smart contract environment feel familiar, teams can focus on product instead of rewriting their entire stack.

Then there’s the part people often argue about: traction. No metric is perfect, and it’s easy to inflate address counts or transaction totals in crypto. Still, network activity can be a useful stress signal. Vanar’s mainnet explorer currently shows about 193,823,272 total transactions, 28,634,064 wallet addresses, and 8,940,150 blocks. I don’t treat that as proof of success. I treat it like mileage on an engine. It suggests the network has been used enough to encounter real-world patterns like bursts, churn, spam attempts, and normal everyday noise. Those experiences force systems to harden in ways a quiet testnet never does.

The token side matters because Vanar’s fee philosophy and its security incentives depend on VANRY as the gas and staking asset. Public trackers list VANRY with a max supply of 2.4 billion, and circulating supply figures in the low 2.2 billion range depending on the source and method. The whitepaper explains the supply design more directly: it describes 1.2 billion minted at genesis for a 1 to 1 swap from the earlier TVK supply, with the remainder emitted as block rewards over roughly 20 years. That long issuance schedule is important if you care about network security and validator incentives. A chain can’t rely on vibes to stay secure. It needs a real economic engine that keeps validators motivated and keeps the network functional as activity grows.

Vanar’s validator story also comes across as pragmatic rather than idealistic. The whitepaper describes starting with a Proof of Authority setup and layering in a Proof of Reputation mechanism with community voting as the validator set opens up. That kind of model tends to divide people, but again, it matches the broader theme: prioritize stability and operational control early, then widen participation with reputational gates and governance structures.

If I had to describe Vanar without sounding like a brochure, I’d use a simple comparison: most chains want to be a new highway. Vanar feels more like the back office that keeps a stadium running. The fans don’t care how the staff schedule is optimized or how the ticket scanners sync. They only care that the line moves and the show starts on time. That’s what consumer adoption really looks like. People don’t praise infrastructure. They only notice it when it fails.

The interesting tension is that Vanar sits across multiple verticals: gaming, metaverse, AI, eco, brand solutions. On the surface, that can look like “every narrative at once.” But there’s another way to read it. Those verticals share the same basic building blocks: ownership, rewards, collectibles, identity-like actions, payments-like transfers. The vertical changes, but the primitives repeat. If Vanar can make those primitives cheap, stable, and easy for developers, then different kinds of products can reuse the same rail without reinventing the foundations each time.

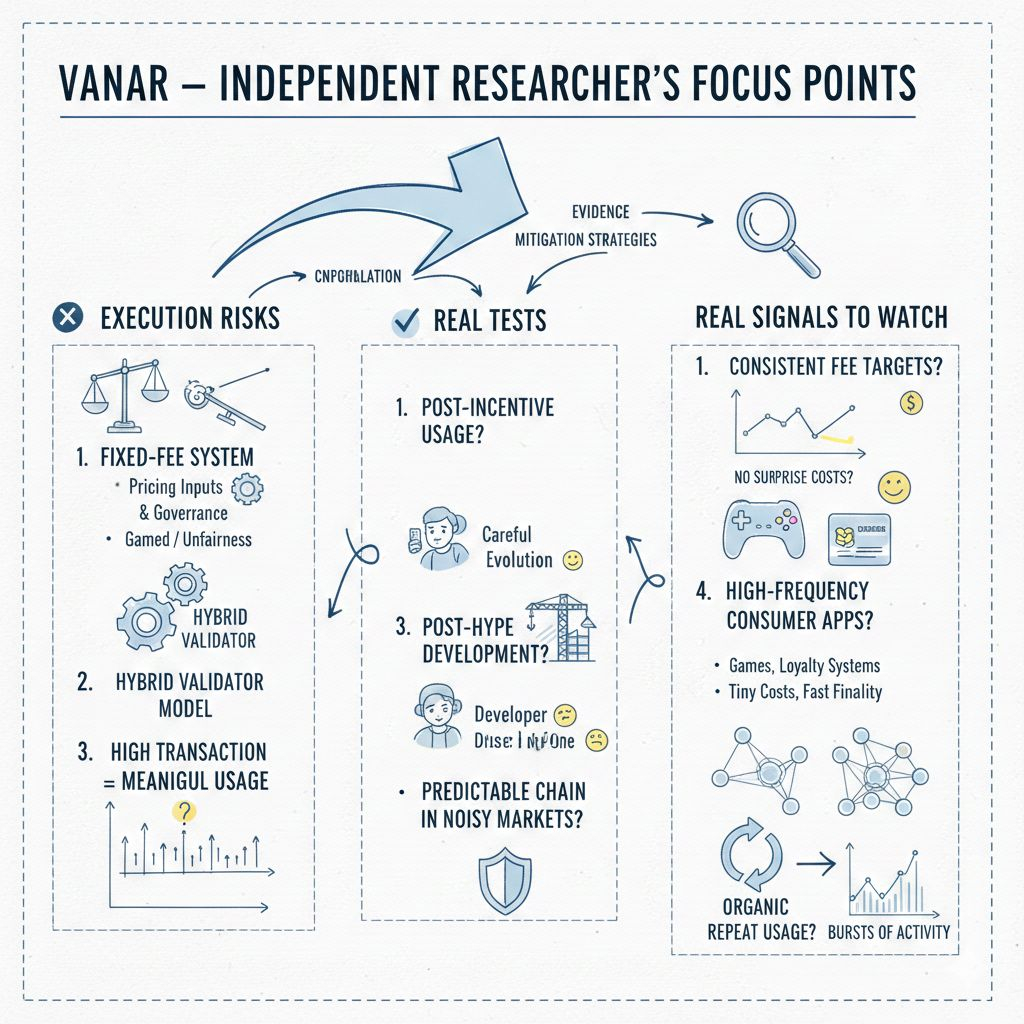

None of this removes the execution risk. A fixed-fee system needs strong pricing inputs and good governance, or it can be gamed or drift into unfairness. A hybrid validator model needs careful evolution, or it can end up pleasing no one. And high transaction counts do not automatically equal meaningful usage. The real test is whether people keep using applications when incentives are gone, whether developers keep building when the hype cycle moves on, and whether the chain remains predictable when markets get noisy.

So if I were watching Vanar like an independent researcher, I’d focus on a few very real signals. Do the fee targets stay consistent through volatility, or do users start feeling surprise costs again? Do consumer apps build high-frequency loops on Vanar, like games and loyalty systems, where tiny costs and fast finality actually matter? Does validator participation broaden in a way that’s visible and stable over time? And do the on-chain patterns reflect organic repeat usage, not just bursts of activity?

My overall takeaway is that Vanar’s most meaningful bet is not “we are the loudest chain” but “we are the most reliable chain for everyday actions.” That’s a less exciting slogan, but it’s a better recipe for real adoption. In the end, if Vanar succeeds, the funniest outcome is that users will barely talk about it. They’ll just keep showing up, because nothing got in their way.