@Dusk Title: Does DUSK Actually Reduce Compliance Costs for Institutions, or Just Shift Them Elsewhere?

DUSK presents itself as a purpose-built Layer-1 for “regulated finance”: a privacy-first blockchain that claims to let institutions issue, trade and settle tokenized securities while preserving confidentiality and satisfying regulators. That dual promise—confidentiality without regulatory friction—is the core selling point. On paper the tech looks smart: selective disclosure, zero-knowledge proofs embedded in the protocol, and native compliance primitives aimed at letting a regulator or auditor verify required facts without exposing full transactional detail. But selling the idea and delivering net reductions in real compliance cost are two different things. This article examines the mechanisms behind DUSK’s claim, measures where real savings could arise, identifies the places where costs simply move rather than disappear, and tests the thesis with a real-world example of DUSK’s institutional outreach and partnerships.

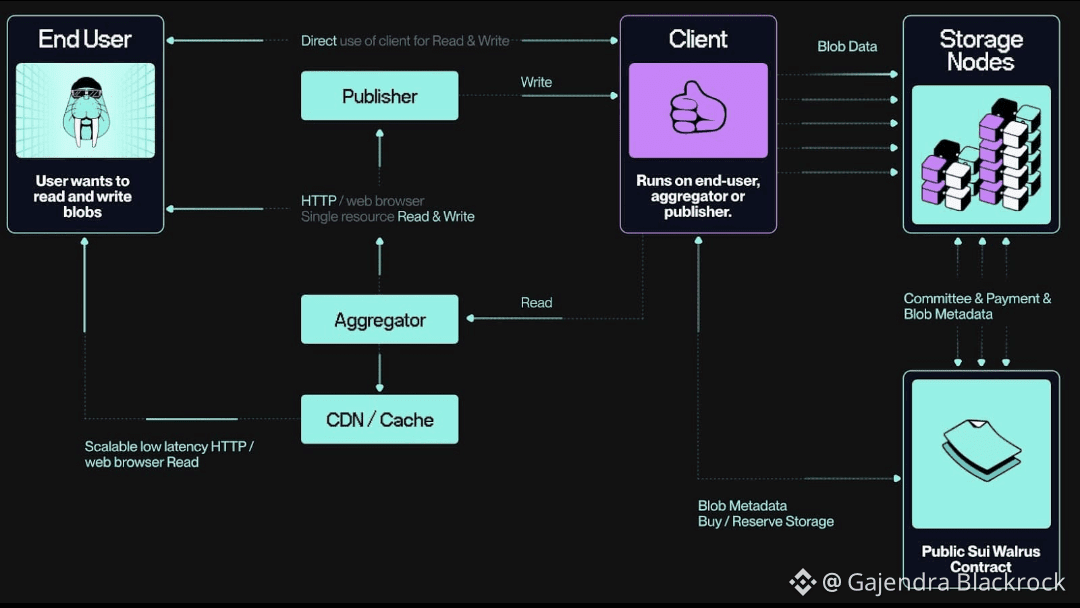

At the protocol level, DUSK uses zero-knowledge techniques to enable what the team and partners call “selective disclosure” or “zero-knowledge compliance” (ZKC). Instead of publishing addresses, amounts and counterparties in the clear, a participant proves—via a ZK proof—that they meet a compliance predicate (for example, that they aren’t on a sanctions list, or that a transaction stays inside a permitted counterparty class) without revealing the raw data. That shifts the cryptographic burden away from exposing data and toward generating and verifying proofs. Practically, an issuer or custodian can prove to a regulator that a set of on-chain transfers respected KYC/AML gates without handing over every wallet balance or every transfer log. That is the core engineering idea for cutting down the manual audit and data-gathering work that typically drives compliance hours.

These ZK primitives can reduce front-line operational burden in three clear ways. First, auditors spend less time assembling and redacting transaction dumps when a compact proof demonstrates compliance for whole classes of actions. Second, institutional counterparties can avoid expensive bilateral data-sharing agreements or reconciliations because the blockchain—and its compliance layer—becomes the canonical, provable record. Third, for certain regulated products (tokenized securities or RWA settlements), on-chain settlement with selective disclosure eliminates many reconciliations and custody reconciliation steps that traditionally generate fees and margin. Each of these is a plausible source of real dollar savings—fewer manual reconciliations, less legal time for bespoke NDAs, fewer delayed settlements that cause funding and opportunity costs.

But these are best-case savings. There are three structural ways costs get shifted instead of eliminated. The first is the engineering and integration cost. DUSK’s privacy stack does not magically replace back-office systems; custodians, broker-dealers and compliance teams must integrate DUSK-specific tooling, build or buy connectors to existing KYC providers, and train staff to interpret ZK proofs and selective-disclosure reports. Those one-time integration projects are not trivial—expect external consulting, new internal tooling, and regulatory engagement costs. If an institution is large enough, that engineering amortizes over volume; for smaller firms, the integration cost can exceed any transaction-level savings for years. Documentation and community resources reduce friction, but they do not make integration free.

The second cost shift is governance and legal complexity. On-chain selective disclosure gives a regulator a Boolean “proof” that some predicate holds, but regulators still want legal accountability, audit trails, and chains of custody for dispute resolution. That means lawyers and compliance officers will still demand access to underlying attestations, logs of how identity assertions were bound to keys, and contractual guarantees from custodians and oracle providers. In practice, legal teams repackage ZK outputs into compliance packages and service-level agreements. Those packages reduce the tedium of transaction-by-transaction review but create a new category of oversight work—certifying oracle sources, validating on-chain identity anchors, and negotiating the extent of “selective disclosure” that’s contractually permitted. Those activities create recurring governance costs.

Third, there is the regulatory tail-risk and supervisory cost. Privacy-preserving features attract extra scrutiny. Regulators in many jurisdictions are still figuring out how to supervise systems where raw data is intentionally hidden. To approve DUSK-based products an institutional issuer may need to run pilot programs, provide sandbox demonstrations, and make commitments about regulator access in exceptional cases. That process is costly and time-consuming; where regulators insist on enhanced on-prem oversight or escrowed decryptable logs, the savings from automated proofs can be offset—or even outweighed—by the time and resources devoted to convincing supervisors the system is safe. Recent commentary in industry outlets highlights that privacy-focused chains often face more friction during onboarding precisely because they force regulators to invent new supervision practices.

A practical way to see the net effect is to examine a real partnership or pilot. DUSK’s public announcements reveal work with regulated issuance platforms and NPEX (a Dutch exchange initiative) and the adoption of Chainlink interoperability standards to bind off-chain attestations into on-chain proofs. Those moves are meaningful: they show DUSK is pursuing the institutional credential pathway rather than chasing anonymous retail hype. In such pilots, early evidence suggests the largest operational savings accrue to the issuer and the central custodian who control the identity binding and can therefore reduce expensive bilateral reconciliations. But the counterparty side—brokers, corporate legal, and external auditors—often face additional upfront work to accept the new proof formats and update their procedures. So the practical distribution of savings is uneven: issuers and primary custodians capture most of it; downstream intermediaries absorb integration and training costs first.

Consider a hypothetical but realistic use case: a mid-sized private markets sponsor tokenizes a portfolio of SME loans on DUSK and needs to report to an EU regulator and multiple investors. Using DUSK’s selective-disclosure model, the sponsor can publish confidential transfer proofs that assert investor eligibility (KYC/AML) and the validity of transfers without publishing investor identities. Compared with a manual process—collecting spreadsheets, redacting sensitive cells, and sending them to hundreds of investors and auditors—the sponsor saves substantial time and legal review hours. That is a concrete compliance cost reduction for the sponsor. However, investors and auditors will want to independently verify these assertions, and if they lack the technical capacity to validate ZK proofs, they will engage third-party forensic vendors or request monthly unredacted reconciliations under strict NDAs. Those verification vendors and NDA processes introduce an alternative, sometimes recurring, cost stream. Net savings therefore depend on the ecosystem’s maturity: if reliable third-party verifiers and auditors exist that can validate DUSK proofs at scale and reasonable price, net savings materialize; if not, the savings are partial and front-loaded to the issuer.

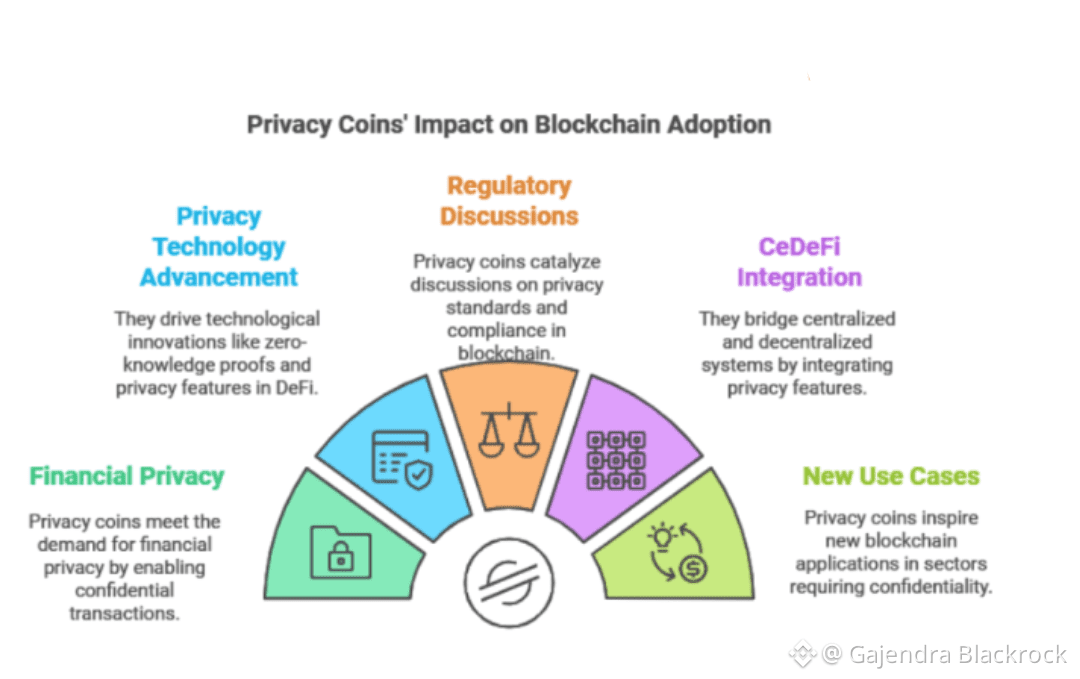

There is an economic nuance often overlooked in vendor narratives: not all compliance costs are linear per transaction. Many compliance expenses are fixed or step-functioned—certifications, annual audits, and legal frameworks. If DUSK reduces the variable cost per transaction but requires a significant fixed investment to prove to regulators that the new model is sound, institutions with high transaction volumes will realize the upside, while low-volume players will not. In other words, DUSK can widen the competitive gap: large incumbents can leverage on-chain privacy to cut unit costs, while smaller players get saddled with disproportionate integration burdens. The technology may therefore concentrate benefits rather than distribute them.

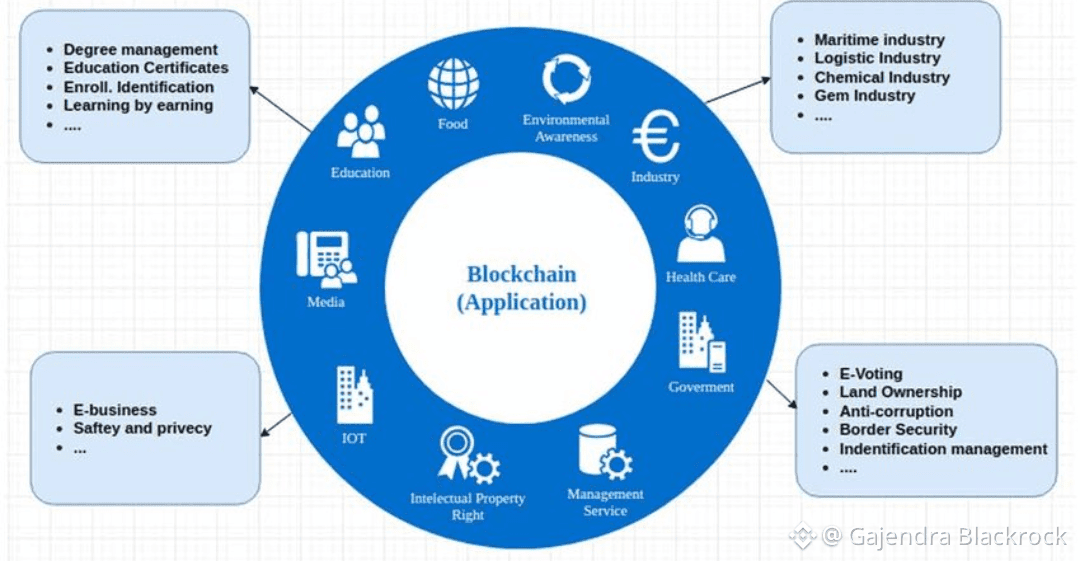

Comparing DUSK to other privacy solutions makes this trade-off sharper. Monero offers default anonymity but no path for regulatory selective disclosure; Zcash provides optional selective transparency via shielded transactions but historically has had less investment in institutional tooling. DUSK’s pitch is specialized: it embeds compliance primitives and tries to be a “licensed stack” for regulated markets. That specialization means DUSK can reduce certain compliance tasks more than general-purpose privacy coins, but the price is dependency on the ecosystem: auditors, KYC providers, oracle partners and legal frameworks tailored to DUSK’s primitives. If those partners are absent or expensive, the expected cost reductions are optimistic. From an institutional perspective, the relevant question is not whether privacy exists but whether an entire compliance product stack (auditors, regulators, custody, insurance) exists around that privacy model. On that metric, DUSK is farther along than most nascent privacy L1s but behind established financial rails.

Operational security and key management are another cost center that can erode claimed savings. DUSK preserves privacy on-chain, but custody and identity anchors still live off-chain with custodians, KYC providers, or institutional key managers. Those custodians must be contractually accountable and often require insurance, audits and SOC reports. The design choice to put identity binding off-chain (and only proofs on-chain) avoids some regulatory headaches but moves the compliance and operational burden into the custody and oracle layer. Institutions will therefore spend on insurance premiums, developer time vetting oracle integrity, and continuous controls monitoring. Those are ongoing costs that scale with assets under custody and cannot be ignored when calculating net savings.

A second real-world test is market behavior under stress. Privacy can hide intent. In trading, hidden large orders remove price signaling and can reduce front-running, which is economically valuable to large funds. However, regulators worry that hiding intent might also hide market manipulation or insider trading. If regulators decide that privacy in settlement requires additional ex-post disclosure thresholds (for example, after a certain size or within an investigation), then the “fast, private settlement” advantage will be counterbalanced by mandatory audit windows and investigator processes. Those investigator processes are costly, both in direct fees and in potential fines or reputational costs. The ability to limit those occurrences—via robust governance, strong market surveillance tools built on top of DUSK, and pre-arranged regulator access—determines whether privacy reduces net compliance cost or merely relocates it to episodic, high-cost investigations.

So, does DUSK “actually” reduce compliance costs? The short, qualified answer is: sometimes. For well-structured issuance and custody flows where the institution controls the identity binding and can standardize proof validation across counterparties, DUSK’s primitives can materially lower variable reconciliation and audit labor, shorten settlement chains, and thus reduce recurring operational expenses. For institutions that trade large volumes or manage large pools of tokenized assets, those savings can be meaningful. However, those benefits are conditional. They require a mature ecosystem of verifiers, auditors and regulators that accept ZK proofs as equivalent evidence; they require custodians who are trusted and insured; and they require legal frameworks that limit ad-hoc disclosure demands. In the absence of those conditions, many savings are offset by integration costs, new governance work, and recurring verification expenses.

A few practical recommendations follow from this evaluation. Institutions considering DUSK pilots should budget for three things explicitly: engineering and integration costs (connectors, proof validators, APIs), legal and governance work (contracts that define selective disclosure thresholds and emergency access procedures), and third-party verification services (auditors or verifiers who can independently validate ZK proofs). They should negotiate commercial models (subscription vs transaction fees) with custodians and verification vendors to ensure the business case aligns with expected transaction volumes. Finally, institutions should pilot with low-regret products—where privacy is a clear product differentiator and regulatory risk is manageable—before attempting core treasury or high-value principal activities on a new privacy chain.

From a public policy and ecosystem perspective, DUSK’s trajectory matters. If regulators and standard-setters converge on frameworks that accept ZK proofs as auditable artifacts, the whole industry benefits because compliance processes can be automated without wholesale data exposure. On the other hand, if regulatory regimes demand decrypted logs for supervision or subject privacy chains to additional oversight, the operational burden will move to escrowed logs, auditors and supervised gateways—costs that will be paid by institutions one way or another. The key hinge is regulatory acceptance: technology can make proofs, but institutions need legal certainty that those proofs suffice.

Concluding assessment: DUSK has engineered plausible mechanisms to reduce certain categories of compliance cost—chiefly reconciliation, repetitive audit work, and settlement friction—when used inside a controlled institutional flow. The savings are most tangible to the entity that owns the identity binding and can standardize proof verification across counterparties. However, those gains are not universal; costs migrate to integration, governance, custody insurance, and verification services. Whether the net balance is positive depends on transaction volumes, the maturity of the DUSK ecosystem (custodians, verifiers, legal templates), and, crucially, how willing regulators are to accept ZK proofs as evidence. Institutions that understand these boundary conditions and plan for the shifted costs will capture benefits; those that treat DUSK as a plug-and-play cost-reducer without budgeting for ecosystem building will likely find the savings smaller than advertised.

Suggested sources and images for further reading and visual assets: The DUSK documentation and technical overview for selective disclosure and the XSC (confidential contract) standard.

Recent platform and ecosystem articles on Binance Square and KuCoin analysis that compare DUSK’s institutional focus to other privacy solutions. These articles contain diagrams of DUSK’s proof flows useful for slide decks.

PR coverage of DUSK’s partnerships (NPEX and Chainlink interoperability announcements), which are useful as a concrete case study of how DUSK is positioning for regulated issuance. The PRs typically include partner logos and schematic images for presentations.

High-level privacy coin comparisons from Chainalysis and CoinDesk for regulatory context and the trade-offs between different privacy architectures. Useful images: comparative feature tables and timeline charts showing regulator actions.