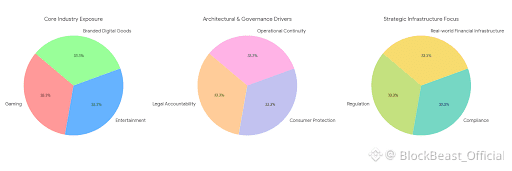

When evaluating a project like Vanar from the vantage point of regulation, compliance, and real-world financial infrastructure, the first thing that stands out is not what it promises, but what it implicitly avoids. Vanar does not present itself as a universal solution or a revolutionary rewrite of economic coordination. Instead, it reflects a design posture shaped by exposure to industries—gaming, entertainment, branded digital goods—where legal accountability, consumer protection, and operational continuity are not optional. That background quietly influences architectural and governance choices in ways that are easy to miss if one is only scanning for novelty.

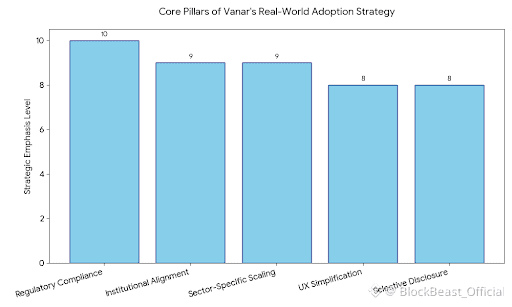

The emphasis on real-world adoption often gets reduced, unfairly, to a marketing slogan in this space. In practice, it usually means something more restrained: minimizing friction for users who do not think in terms of wallets, private keys, or governance tokens; designing systems that can coexist with consumer protection regimes; and accepting that intermediaries, compliance checks, and selective visibility are not aberrations but structural realities. Vanar’s orientation toward games and entertainment implicitly acknowledges this. These sectors operate at scale, under licensing regimes, IP constraints, and jurisdictional oversight. A blockchain meant to support them cannot rely on ideological purity; it must be operationally legible to counterparties who answer to regulators, auditors, and boards.

Privacy, in this context, is best understood as a continuum rather than a binary. Absolute opacity is rarely compatible with regulated environments, but neither is full transparency. Systems that endure tend to allow selective disclosure: the ability to prove compliance without exposing unrelated user data, to enable auditability without broadcasting sensitive commercial information. Vanar’s approach appears aligned with this middle ground, treating regulatory visibility as a design parameter rather than an afterthought. This is less about conceding to oversight and more about acknowledging that institutional participants require predictable mechanisms for reporting, investigation, and dispute resolution.

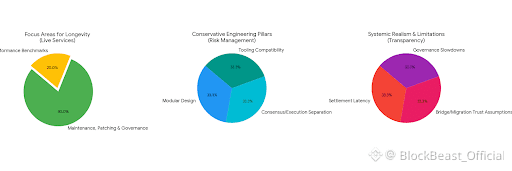

Architecturally, conservative engineering choices matter more than novel abstractions. Modular design, separation of consensus from execution, and compatibility with established developer tooling are not technical flexes; they are risk-management strategies. They allow parts of the system to evolve without forcing disruptive, chain-wide migrations. They make audits more tractable and upgrades less brittle. For teams responsible for live services—games with daily active users or branded environments tied to contractual obligations—this kind of predictability is often more valuable than raw throughput or experimental features. Longevity is built less on performance benchmarks and more on the ability to maintain, patch, and govern infrastructure without destabilizing dependent applications.

Acknowledging limitations is part of that realism. Settlement latency, even when acceptable for many consumer use cases, still constrains certain financial interactions. Bridges and migrations introduce trust assumptions that cannot be eliminated, only managed and disclosed. Governance processes slow down change, sometimes uncomfortably so, but they also reduce the risk of unilateral decisions that can unravel downstream integrations. These are not defects unique to Vanar; they are characteristics of any system attempting to balance decentralization with operational accountability. What matters is whether they are treated transparently and planned for, rather than obscured behind aspirational language.

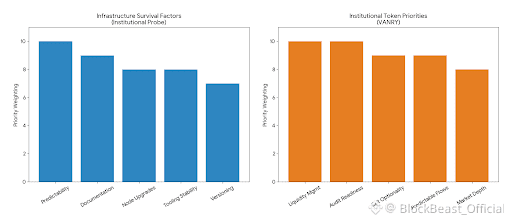

The unglamorous aspects of infrastructure often determine whether a network survives beyond its initial cohort. Node upgrade procedures, documentation clarity, tooling stability, and operational predictability are the things institutions probe first, even if they rarely feature in public discourse. A chain that cannot communicate changes clearly or manage versioning responsibly will struggle under audit or regulatory review, regardless of its theoretical elegance. Vanar’s focus on products that must operate continuously—metaverse environments, game networks—suggests an implicit appreciation for this reality. Downtime, ambiguous behavior, or undocumented edge cases are not merely technical inconveniences in these contexts; they translate directly into contractual risk.

The VANRY token, viewed through an institutional lens, is less about upside narratives and more about liquidity management and exit optionality. Tokens that function as infrastructural assets must support predictable flows, sufficient market depth, and mechanisms for participants to enter and exit without destabilizing the ecosystem. For regulated entities, the ability to unwind positions, account for holdings, and explain exposure to auditors matters more than incentive schematics or speculative appreciation. A token aligned with operational use rather than abstract value capture is more likely to be treated as a tool than as a liability.

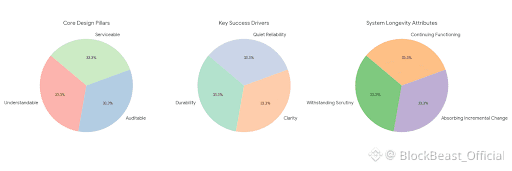

Taken together, Vanar reads as infrastructure shaped by familiarity with constraints rather than a desire to escape them. It is not designed to be invisible to regulators, nor to overwhelm them with complexity, but to be understandable, auditable, and serviceable over time. In a space where visibility and virality often masquerade as success, there is something deliberately modest about this posture. Systems that last are rarely the loudest. They are the ones that withstand scrutiny, absorb incremental change, and continue functioning when enthusiasm fades. If Vanar succeeds, it is likely to be for those reasons—durability, clarity, and quiet reliability—rather than for any single feature or narrative.