Every system begins with assumptions. Some are written down, some are implied, and some are simply inherited because they worked once and nobody bothered to question them again. In the early stages, those assumptions feel harmless. The system functions, users adapt, and everything seems aligned. The danger doesn’t appear when assumptions are wrong. It appears when they are never revisited.

Every system begins with assumptions. Some are written down, some are implied, and some are simply inherited because they worked once and nobody bothered to question them again. In the early stages, those assumptions feel harmless. The system functions, users adapt, and everything seems aligned. The danger doesn’t appear when assumptions are wrong. It appears when they are never revisited.

That’s the quiet tension sitting beneath projects like Walrus. Technically, Walrus does what it sets out to do. Data is stored. It’s verifiable. It’s persistent. Once information enters the system, it doesn’t disappear or quietly change. From an engineering perspective, that’s a success. But long-lived systems don’t just preserve data they preserve intent. And intent doesn’t age as well as code.

People change faster than systems do. Risk tolerance shifts. Priorities evolve. What felt acceptable at one point in time can feel uncomfortable later, even if nothing about the underlying data is incorrect. When a system treats past decisions as permanent signals, it assumes that yesterday’s context still applies today. Most of the time, that assumption goes unchallenged because nothing visibly breaks.

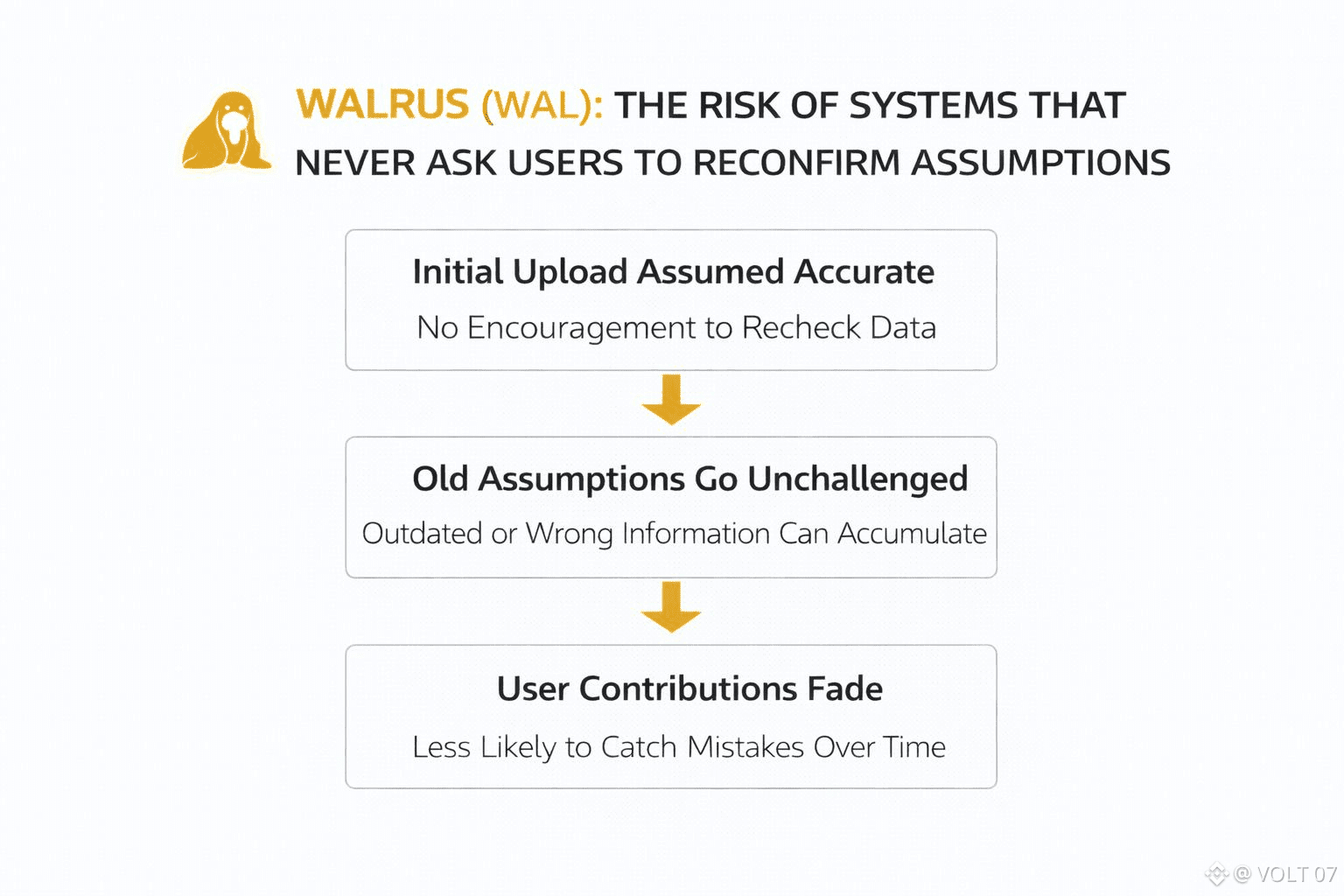

This is where the risk hides. Everything keeps running the protocol operates precisely as intended. Data remains accurate. And yet, over time, the system starts acting on meanings that no longer reflect reality. Old behaviors continue to influence outcomes. Actions that users might not repeat now are used to create patterns. The system grows more confident in its understanding, while users slowly drift away from that understanding without realizing it.

What makes this especially tricky is that there’s no obvious moment of failure. No exploit. No crash. No headline-worthy incident. The misalignment builds quietly. Decisions get made based on technically correct information that no longer represents what users intend. From the system’s point of view nothing is wrong. From the user’s point of view, something feels off but it’s hard to explain why.

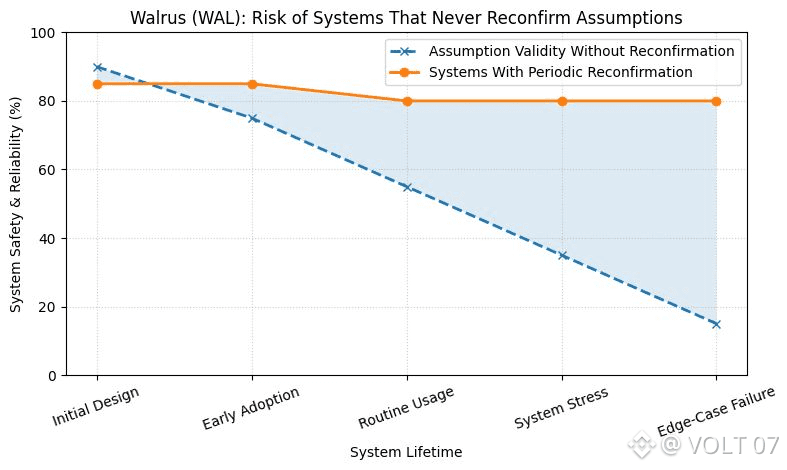

Traditional systems learned to deal with this through friction. Permissions expire. Settings need renewal. Agreements get revisited. These moments aren’t inefficiencies; they’re checkpoints. They force assumptions back into the open. They give people a chance to say, “Yes, this still makes sense,” or “No, this doesn’t reflect me anymore.” Without those pauses, systems don’t just remember facts they remember decisions long after the people behind them have moved on.

Walrus doesn’t create this problem, but it makes it impossible to ignore. A data layer that never forgets also never asks follow-up questions. It assumes continuity where there may be none. And when silence is treated as consent, the system stops listening by default. Over time even if both sides are acting in good faith, the gap between what the system thinks and what users really want becomes wider and wider.

This is actually the point at which the risk becomes systemic. The focus is no longer on individual users or isolated data points. Rather, it is a structure that gathers old and out, of, date user intents and has them as current truths. At scale, that kind of drift can shape incentives, influence decisions, and lock ecosystems into paths they didn’t consciously choose.

None of this means Walrus is broken or misguided. It means it sits at the edge of a deeper challenge facing all permanent data systems. Decentralization is very good at preserving information. It’s far less practiced at revisiting meaning. And meaning is where assumptions live.

As decentralized infrastructure matures, correctness alone won’t be enough. Systems will need ways to acknowledge that people change, even when data doesn’t. They’ll need moments of reconfirmation, not because something went wrong, but because time passed.

The real risk with systems that never ask users to reconfirm assumptions isn’t that they store the wrong data. It’s that they keep using the right data long after it stops representing the people behind it. And in a world where systems scale faster than human reflection, that kind of quiet misalignment can be more dangerous than any obvious error.