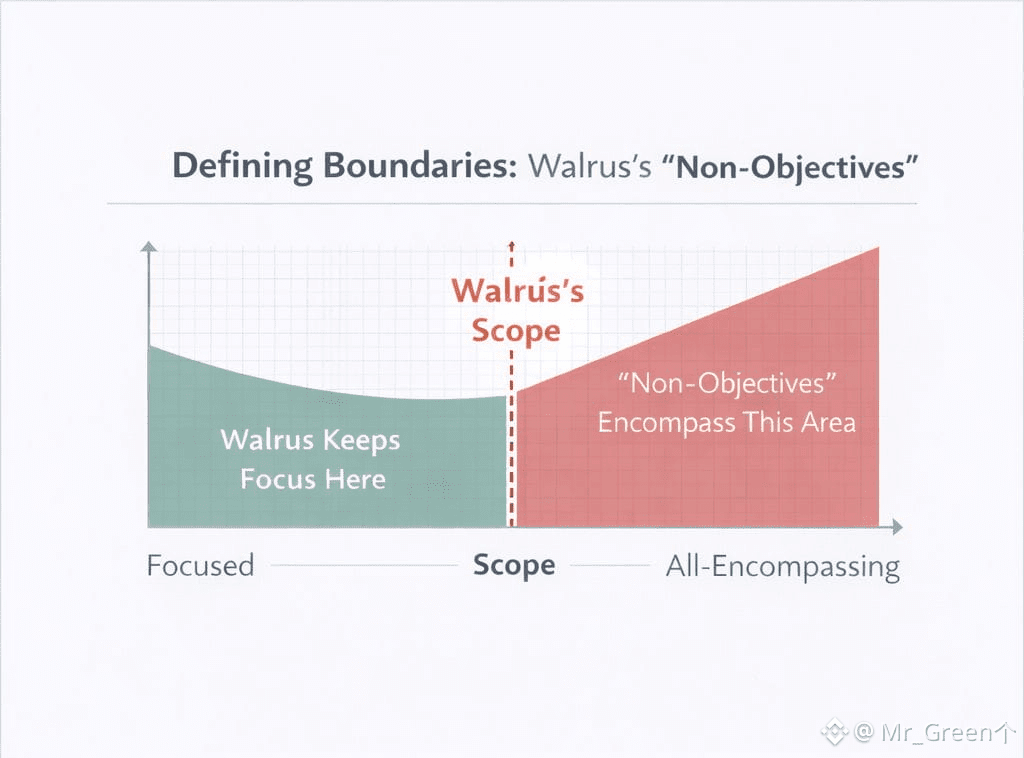

In Web3, projects often lose trust for a simple reason. They promise to replace too many things at once. They try to be storage, execution, identity, CDN, and governance all in one. The result is usually a system that looks impressive on paper but struggles in real life because it cannot be excellent at the basics. Walrus takes a more restrained approach. It is very explicit about what it is trying to do, and also what it is not trying to do. These “non-objectives” are not marketing disclaimers. They are design boundaries that protect reliability.

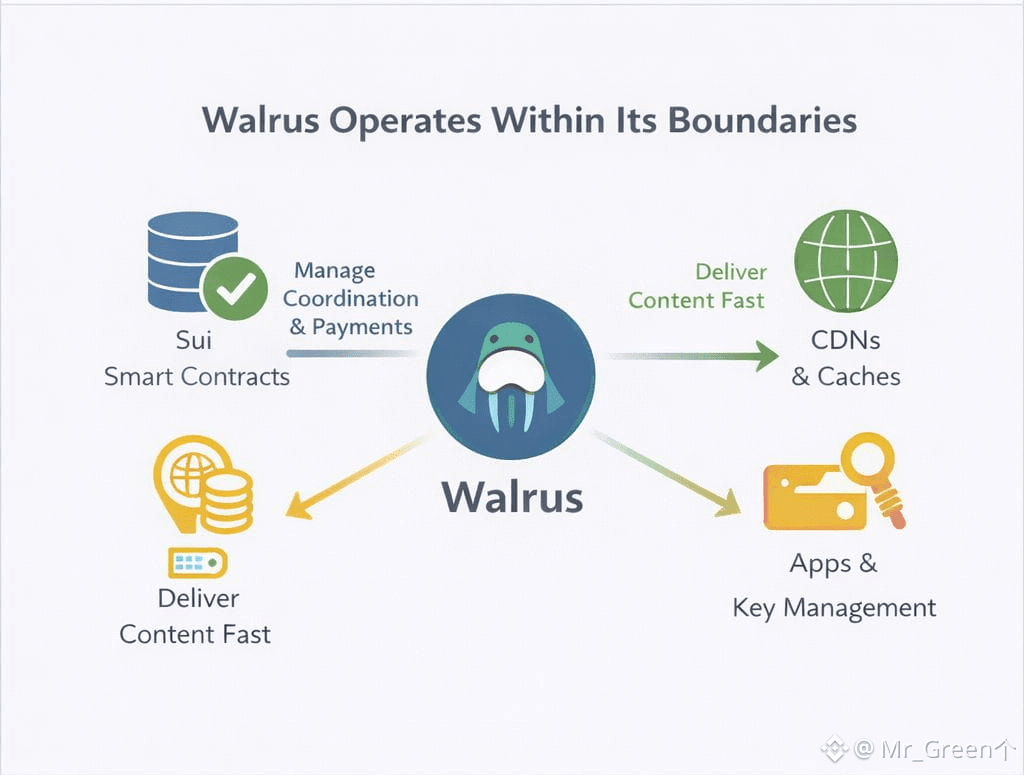

Walrus is a decentralized storage protocol designed for large, unstructured content called blobs. A blob is simply a file or data object that is not stored like rows in a database table. Walrus supports storing blobs, reading them, and proving and verifying their availability. It is designed to keep content retrievable even if some storage nodes fail or behave maliciously. Walrus integrates with the Sui blockchain for coordination, payments, and availability attestations, while keeping blob contents off-chain. Only metadata is exposed to Sui or its validators. From that base, Walrus defines what it does not do.

First, Walrus does not try to reimplement a CDN. It does not claim it will give you tens of milliseconds of global latency by itself. Instead, it is designed so traditional caches and CDNs can be compatible with Walrus. This is a practical choice. CDNs are hard, expensive, and operationally demanding. Walrus focuses on making content correct and retrievable, while allowing speed to come from the infrastructure the web already uses. It also keeps the decentralization story honest: users can still verify what they receive, even when intermediaries help deliver it.

Second, Walrus does not try to reimplement a full smart contract platform with its own consensus and execution. It relies on Sui smart contracts to manage Walrus resources and processes: payments, epochs, committee coordination, and so on. This is another boundary that protects focus. Building a reliable storage network is already a deep problem. Adding a full execution layer would blur responsibilities and introduce new risks. Walrus chooses to specialize and to lean on an existing chain for what chains do best: coordination and public events.

Third, Walrus is not a full private storage ecosystem. It supports storing any blob, including encrypted blobs, but it is not a distributed key management infrastructure. It does not manage encryption or decryption keys. This is important because key management is a separate problem with its own security tradeoffs and user experience challenges. By not baking key management into the protocol, Walrus allows different applications to choose different models: Web2 login, contract gating, token gating, enterprise key custody, or something else. Walrus becomes the storage layer beneath those choices, not the system that dictates them.

These non-objectives create a clearer mental model for builders.

Walrus is the place for large unstructured data.

Sui is the place for coordination, payments, and public attestations.

CDNs and caches are the place for speed and user experience.

Apps are the place for access control and keys.

When responsibilities are separated like this, failures become easier to reason about. If a site loads slowly, you look at caching and delivery. If a blob fails verification, you look at integrity and encoding. If a user cannot decrypt content, you look at keys. When one system tries to own all responsibilities, debugging becomes a fog.

Non-objectives also make Walrus easier to integrate beyond Sui. Walrus states that builders can use it in conjunction with any L1 or L2. That works partly because Walrus is not trying to pull everything into one chain’s execution environment. It keeps heavy data off-chain and keeps the lifecycle record on-chain. Other ecosystems can reference the blob ID and treat Sui events as an availability anchor without needing to move their core logic.

There is also a deeper reliability reason. Walrus is designed to tolerate Byzantine faults and still keep blobs retrievable. It uses encoding and verification. It uses epochs and committees. It uses on-chain events like the Point of Availability and availability periods. If it also tried to be a CDN and a full smart contract platform and a key manager, the core protocol would have more moving parts. More moving parts means more ways to fail, more ways to be exploited, and more ways to confuse end users.

So the restraint is not only philosophical. It is engineering discipline.

In a way, Walrus’s non-objectives are a quiet form of respect for complexity. They say: some problems are already solved well elsewhere, and we should integrate with them instead of rebuilding them. That is how you get systems that are not only clever, but usable.

A good infrastructure project does not only add features. It also refuses features that would weaken its core promise. Walrus’s promise is availability and verifiability for large blobs under imperfect conditions. Its non-objectives are what keep that promise from being diluted.