I did not start caring about fees because I wanted things to be cheaper, I started caring because I got tired of watching cost rewrite behavior without anyone changing a single line of code.

It never shows up as a crisis at first. It shows up as a small accommodation. Someone widens a budget check. Someone adds a buffer, because “gas can spike.” Someone adds a second route, because “this path is sometimes expensive.” Then a retry, then a delay, then a backoff schedule that nobody wants to touch because it’s glued to production now. The workflow still works, the dashboards stay green, and the product team still ships. But the system is no longer doing what you designed, it is doing what the fee market allows.

That is when it clicked for me that, in continuous automation, fees are not a price, they are a contract.

A price is something you pay and forget. A contract is something you build around, repeatedly, under conditions you do not control. If the contract is legible, you can model it. If the contract is not legible, your system starts estimating, and estimation is where complexity breeds.

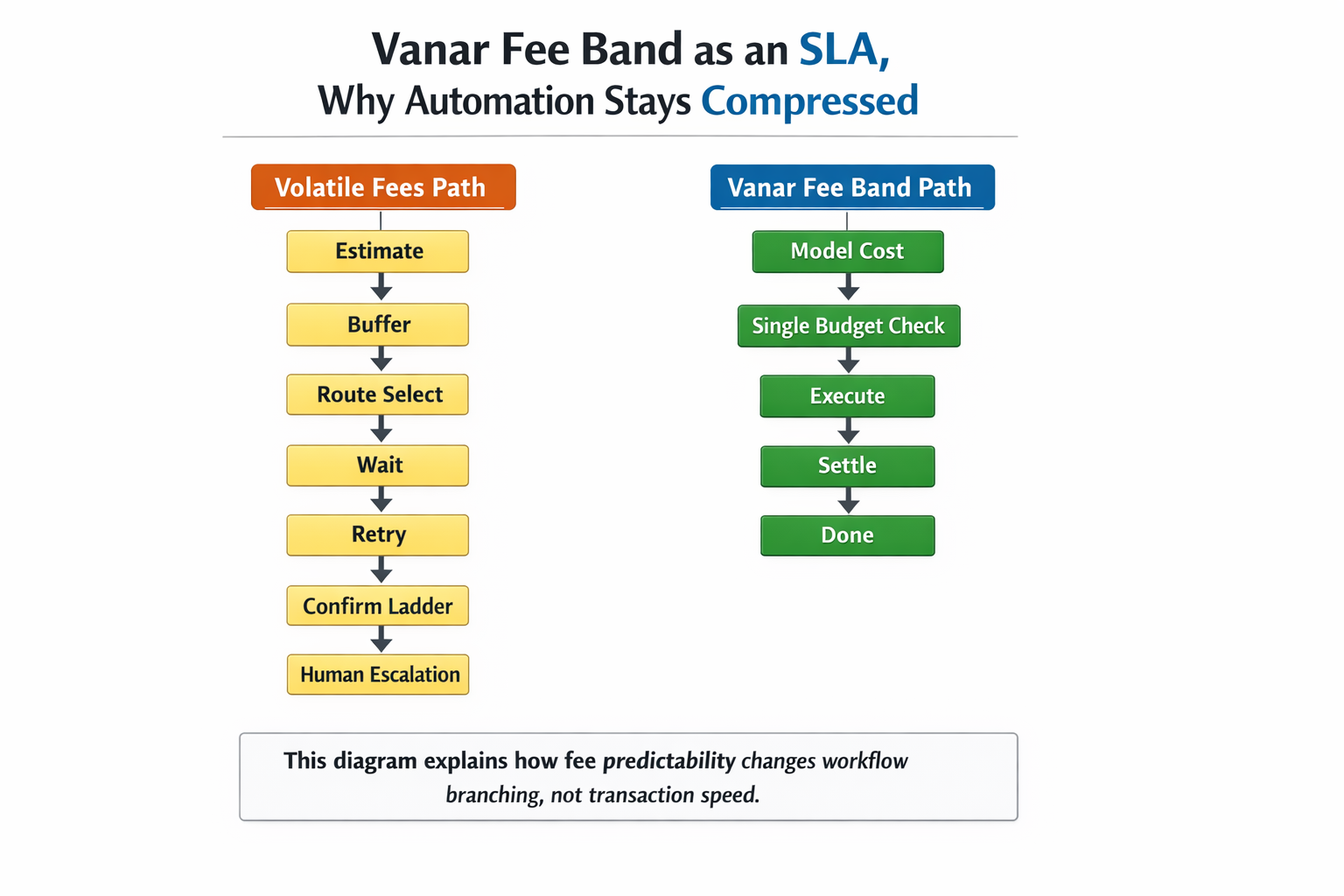

What makes fee volatility dangerous is not the feeling of paying more, it is the fact that volatility forces you to turn deterministic logic into probabilistic logic. A workflow that used to be “if cost is under X, do the thing” becomes “estimate cost, add buffer, choose route, confirm again, wait, retry, maybe split the action, maybe degrade the feature.” That is not just more steps, it is more branches. Branches accumulate, branches become incident hiding places, and branches are what turn clean automation into supervised automation.

I keep coming back to Vanar because Vanar is one of the few chains that seems to treat predictable cost behavior as a first class infrastructure constraint, not a UI nicety.

When a chain treats fees as fully reactive, it is implicitly saying, “your operating assumptions are allowed to change at runtime.” Humans handle that with judgment. We wait, we batch, we decide not to transact, we come back later. Automation does not wait gracefully. Automation branches. It adds a tolerance band, then it adds a second band, then it adds a third band because the first two did not survive the last two weeks of real traffic.

A fee band, when it is real, acts more like an SLA. Not a marketing SLA, not a promise you paste on a landing page, but an engineering SLA, a boundary that upstream systems can safely lean on. If the fee behavior stays inside a controlled range often enough, you stop writing “uncertainty management” code and you go back to writing product code.

That difference is subtle until you operate something for months.

In week one, you can pretend fee variability is just a nuisance. In month six, you realize fee variability is what forced you to introduce a human escalation path, because at some point someone has to decide whether the action is still worth executing. That is the moment autonomy quietly collapses. The system keeps running, but it is no longer running itself.

This is why I think fee bands are inseparable from how a chain treats validator discretion and finality semantics. Those are the other two channels where uncertainty escapes, and they compound each other in production.

If validator behavior allows wide discretion under stress, ordering and timing become soft variables. That matters because ordering is meaning in any serious workflow. “Paid then executed” is not the same as “executed then paid.” “State committed then action triggered” is not the same as “action triggered then state eventually committed.” When ordering drifts, upstream systems respond the only way they can, they add more checks, they add more waiting, they add more confirmation ladders. Again, the base layer stays healthy, but the application layer inflates.

If finality is treated as a confidence curve, you get the same inflation pattern. You can always wait longer, you can always ask for more confirmations. That is workable for human-driven flows. It is poison for automated flows, because a confidence curve never gives you a single moment you can treat as completion. Every team invents a threshold, then a second threshold for “high value,” then a third threshold for “congestion.” Now your system has multiple definitions of “done,” and reconciliation becomes permanent, not exceptional.

The reason I am willing to spend attention on Vanar is that Vanar reads like an attempt to hold all three of those uncertainty channels inside narrower boundaries, because once you let them drift, you do not pay the bill at the protocol layer. You pay it in downstream complexity.

A predictable fee band is the cleanest example, because it touches everything. Budgeting becomes deterministic. Scheduling becomes deterministic. State machines compress. Completion becomes binary instead of interpretive. In day to day operation, I trust compressed state machines more, because they are easier to audit, easier to reason about, and easier to keep stable under automation.

That trust is not philosophical. It is operational. It comes from seeing how quickly “just add a buffer” turns into “we now maintain a second system whose only purpose is to cope with variability.”

If you take the SLA framing seriously, you stop asking whether a chain is cheap on average. You start asking whether it is predictable enough to be depended on repeatedly. That sounds like a boring question, and it is, but boring questions are the ones that decide whether a system survives after the novelty wears off.

The uncomfortable part is that this kind of predictability is not free, and it is not something you can bolt on later.

To keep fee behavior legible, you often have to give up degrees of freedom that other chains use to optimize dynamically. You have to be less elastic under congestion. You have to be more opinionated about how pricing can move. You have to accept that sometimes you will not capture the “most efficient” market clearing behavior, because you are prioritizing modeling over micro-optimization.

That trade-off is real. Builders who like improvisation at runtime will feel constrained. Some composability patterns become harder, because composability thrives on open-ended behavior. A fee band is, by definition, a constraint on open-ended behavior. It forces you to choose which degrees of freedom matter, and which ones you are willing to lock down.

That can make a chain look less alive.

Markets love the feeling of aliveness. Parameters changing, fees reacting, incentives shifting, governance responding. It looks like progress. But in production, aliveness often just means someone is constantly tuning the system to keep it from drifting. It means the chain is stable because humans are watching, not because the rules are legible enough to stand on their own.

Vanar’s bet, as I read it, is that legibility beats aliveness when what you are building is meant to run unattended.

I am not claiming this is universally superior. There are environments where flexible fee markets and probabilistic settlement are perfectly acceptable, even desirable. If your primary user is a human and your workflow is episodic, you can absorb uncertainty. You can make choices in the moment. You can decide that today is not the day to execute. A lot of crypto activity lives there.

But the direction that keeps pulling my attention is the one where workflows do not pause, agent loops do not sleep, and value movement is part of the loop, not a separate ceremony. In those environments, volatility does not remain a detail. It becomes a behavior-shaping force. It forces supervision back into the architecture, because someone has to interpret the edge cases.

If Vanar wants to matter in that world, the fee band cannot be a slogan. It has to show up as a contract that upstream systems can safely model, under repetition, under load, and over time.

Only near the end does it make sense to mention VANRY, because the token should not be the headline. If the thesis is “predictable completion is valuable,” then VANRY is better understood as part of the coupling mechanism that pays for, coordinates, and secures repeatable execution and settlement behavior. That is less exciting than attention-driven token stories, but it is also more accountable. A token that sits inside completion assumptions only works if completion stays reliable.

I do not know how the market will price that kind of reliability, or when it will care.

I do know what it feels like to operate systems where fees are “efficient” but not legible. You spend your best hours managing uncertainty instead of building capability. You end up with a product that functions, but only because someone is always watching it, ready to intervene when the contract changes underfoot.

That is why I stopped treating fees like a price.

For the systems that actually need to run, fees are a contract, and a contract that keeps rewriting itself is not a contract at all.