The first time I saw a “fast chain” pitch lose the room, it wasn’t because the throughput claim sounded unrealistic or because the demo glitched, it was because a single question exposed the gap between performance as marketing and performance as lived experience: what happens when the market is not polite, when volatility squeezes everyone into the same narrow doorway, and when the network is forced to prove whether it can behave like infrastructure rather than like a best-effort service. In crypto, people love to measure success through averages because averages are clean and easy to repeat, but actual trust is built in moments that are messy and time-compressed, where a ten-minute window can decide a month of PnL and where a user’s perception of “fairness” is shaped less by ideology and more by whether their intent turns into an outcome without the system changing the rules mid-game.

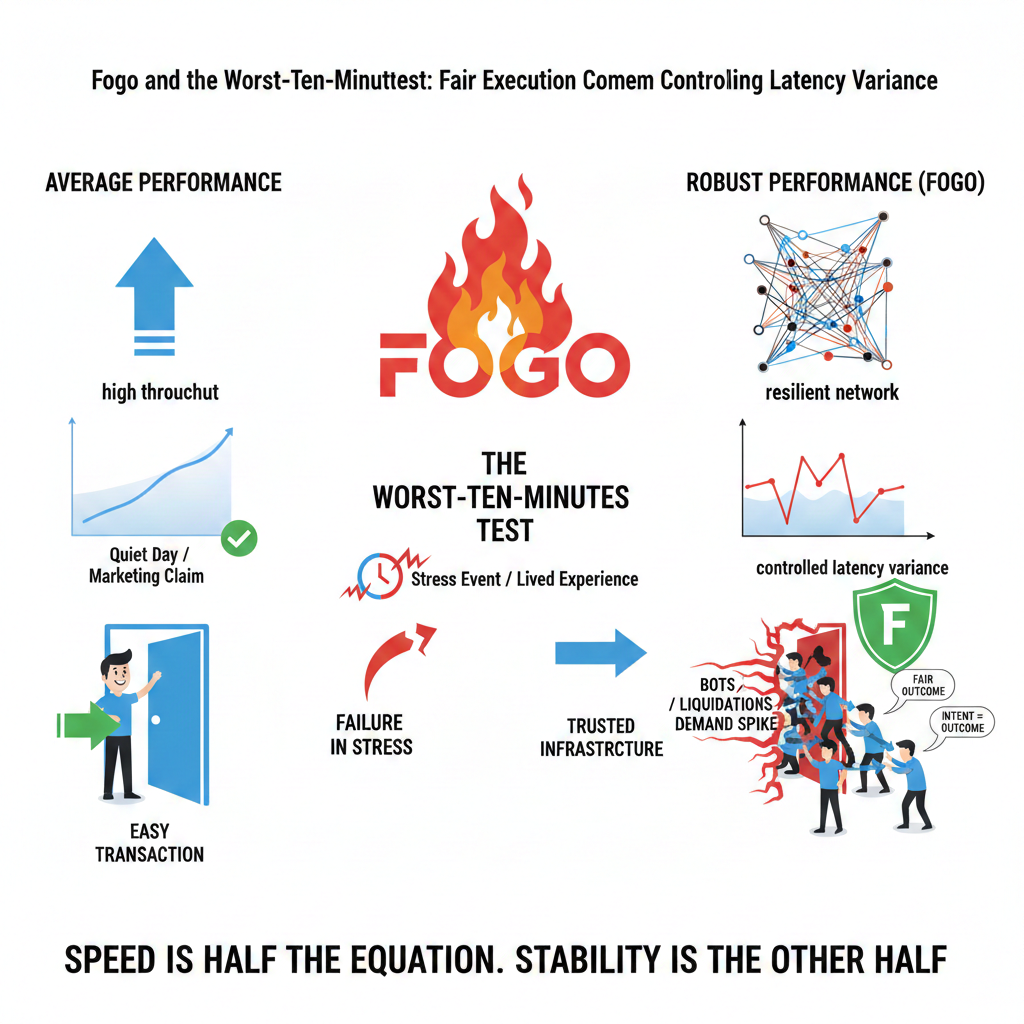

Fogo is often introduced in the same lazy way most high-performance chains are introduced, as if the only thing that matters is being faster than the last chain, but that framing hides the real bet because it turns a venue thesis into a benchmark thesis, and those are not the same product. If you say “Solana style execution,” you already invoke a known feel in crypto: parallel execution, high throughput, the belief that you can unlock applications that resemble real financial software rather than slow onchain rituals; yet the uncomfortable truth is that speed is only half the equation, because the other half is behavioral stability under stress, and the chains that win serious flow are not the ones that feel great on a quiet day but the ones that do not become unrecognizable on the days where demand spikes, bots flood mempools, liquidations cascade, and every participant is simultaneously trying to move before the next candle prints.

The reason “worst ten minutes” matters is not dramatic storytelling, it is an honest description of how users and builders actually experience systems, because almost nobody forms their opinion of an execution environment from steady-state conditions, and nearly everyone forms it from edge cases where the network is congested and where timing becomes the difference between a controlled loss and a chaotic liquidation. In those windows, a chain is not merely executing transactions, it is arbitrating outcomes at scale, deciding who gets a cancel in time, who gets filled first, who eats slippage, who gets a failed transaction that arrives too late to matter, and who gets liquidated because the chain’s behavior itself became part of the risk model; once you see that clearly, the most important question stops being “how fast is it on average” and becomes “how consistently does it behave when everyone is demanding priority at the same instant.”

This is why the real opponent is not latency in the simple sense of “how quickly something confirms,” but latency variance, which is the jitter and tail behavior that turns a technically fast system into a practically unpredictable one, especially when strategies are sensitive to sequencing, cancel-replace loops, and partial fills that only make sense if you can rely on the chain to behave within a narrow band. Two networks can appear similar in headline metrics and still feel radically different because one stays stable in its worst case while the other drifts into a state where execution becomes uneven, retries become the norm, and only the most tuned infrastructure consistently gets the outcomes it expects, which is precisely where fairness stops being a moral argument and becomes a physical one, because the environment quietly begins to reward proximity, tuning, and privileged paths rather than market insight and risk management.

That is where Fogo’s posture becomes easier to understand, because it is not pretending that geography and network topology are abstract details that magically disappear once you call something “decentralized,” it is treating them like the real constraints they are, and then attempting to engineer around them in a way that resembles how trading venues think rather than how general-purpose platforms market themselves. Colocation, validator discipline, and tighter assumptions about how the network is operated are controversial in crypto culture because they feel like they violate the romance of permissionless participation, but in trading infrastructure they are familiar tools, and the logic is blunt: variance in the path between intent and execution is not an academic issue, it changes who can cancel in time, who can avoid slippage, who can compete for fills, and who ends up paying the hidden tax of failed or delayed transactions, which is why traditional markets spend enormous amounts of money reducing not just latency but uncertainty in latency, even if crypto sometimes pretends those dynamics stop existing simply because the market is onchain.

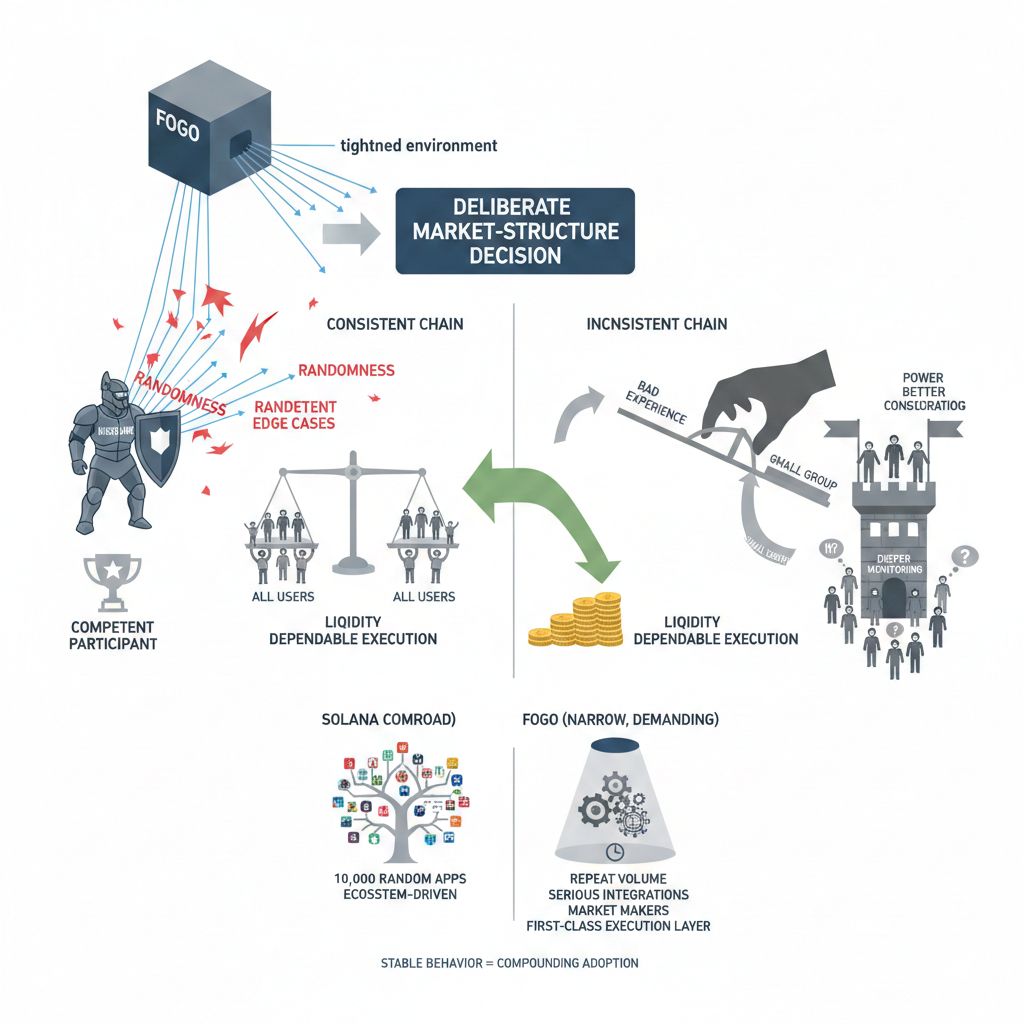

When you view Fogo as an attempt to tighten the environment, the discipline angle starts to look less like a branding trick and more like a deliberate market-structure decision, because reducing randomness at the base layer reduces the number of strange edge cases where execution outcomes depend on being an ultra-optimized participant rather than a competent one. The silent danger in an inconsistent chain is not just that users get a bad experience, it is that power concentrates in the hands of those who can afford better infrastructure, faster retries, smarter routing, deeper monitoring, and more aggressive tuning, which creates a form of execution centralization that does not show up in governance debates but shows up in who reliably wins under stress, and once that pattern emerges it becomes self-reinforcing because liquidity goes where execution is dependable, and dependable execution increasingly belongs to the same small group, leaving everyone else to wonder why the chain “felt fine” until it mattered.

This is also why the shallow Solana comparison misleads, because Solana’s narrative is broad and ecosystem-driven, aiming to be the default home for many categories of applications, while a trading-oriented chain has a different success function that is narrower but more demanding. A venue does not need ten thousand random apps to be real, it needs repeat volume from serious integrations that commit rather than merely deploy, it needs market makers who care enough to tune strategies to the environment because they believe the environment will still be the same next month, and it needs perps and spot systems that treat the chain as a first-class execution layer rather than as a place to list and pray; this kind of adoption looks quiet until it compounds, but it only compounds if the chain’s behavior is stable enough that the base layer stops being a variable traders have to price into every decision.

Once you reach that point, the conversation inevitably drifts into economics, and it should, because a chain cannot live forever on the identity of being “almost free,” especially if it wants to host real trading flow where security, operations, and incentive alignment must be sustained through more than optimism. If fees remain negligible, then the chain still needs a durable way to fund security and keep validators honest; if fees spike under load, then the entire venue promise gets tested because trading strategies are simultaneously fee-sensitive and latency-sensitive, and fee volatility becomes another form of execution variance that destroys predictability at the exact moments where predictability is supposed to be the product. The durable equilibrium in real markets is usually boring and repetitive—reasonable fees, consistent volume, stable rails—because venues become businesses not by charging a fortune per trade but by becoming the place where trades keep happening without the infrastructure adding surprise costs during the moments of stress.

So the strategic question that decides whether Fogo becomes meaningful is not whether the thesis sounds right in a thread, but whether discipline can pull in real flow, meaning repeat volume from participants who have better options and who will not tolerate an environment that changes personality under pressure. If that discipline actually results in a chain that feels stable when the room gets loud, then the outcome will not look like a marketing victory where everyone announces a winner, it will look like a slow behavioral shift where builders stop over-engineering around base-layer weirdness, market makers start treating the network as reliable enough to commit inventory, and traders stop treating the chain itself as a hidden risk factor embedded inside every position.

I keep coming back to the same human intuition because it’s the only one that matters in the end, which is that nobody remembers the average day, and nobody builds deep trust from a calm-day experience, because what people remember is the day the market moved like it had teeth and the system either held its shape or it didn’t. If Fogo can pass that worst-ten-minutes test repeatedly, without needing to be heroic and without needing to be perfect, then it will not need to shout about benchmarks or posture about ideology, because the people who care about execution will do what they always do: they will quietly migrate toward the place that behaves, and the simplest way I can say what that means, without turning it into a slogan, is that I want a chain that doesn’t change on me when I’m already under pressure.