The detail that made me slow down when studying Plasma was not performance, not throughput, not even fee behavior. It was how aggressively the system narrows what a valid state change is allowed to look like.

That might sound like a low level technical choice, but in my experience, this is exactly where many infrastructures quietly accumulate long term risk.

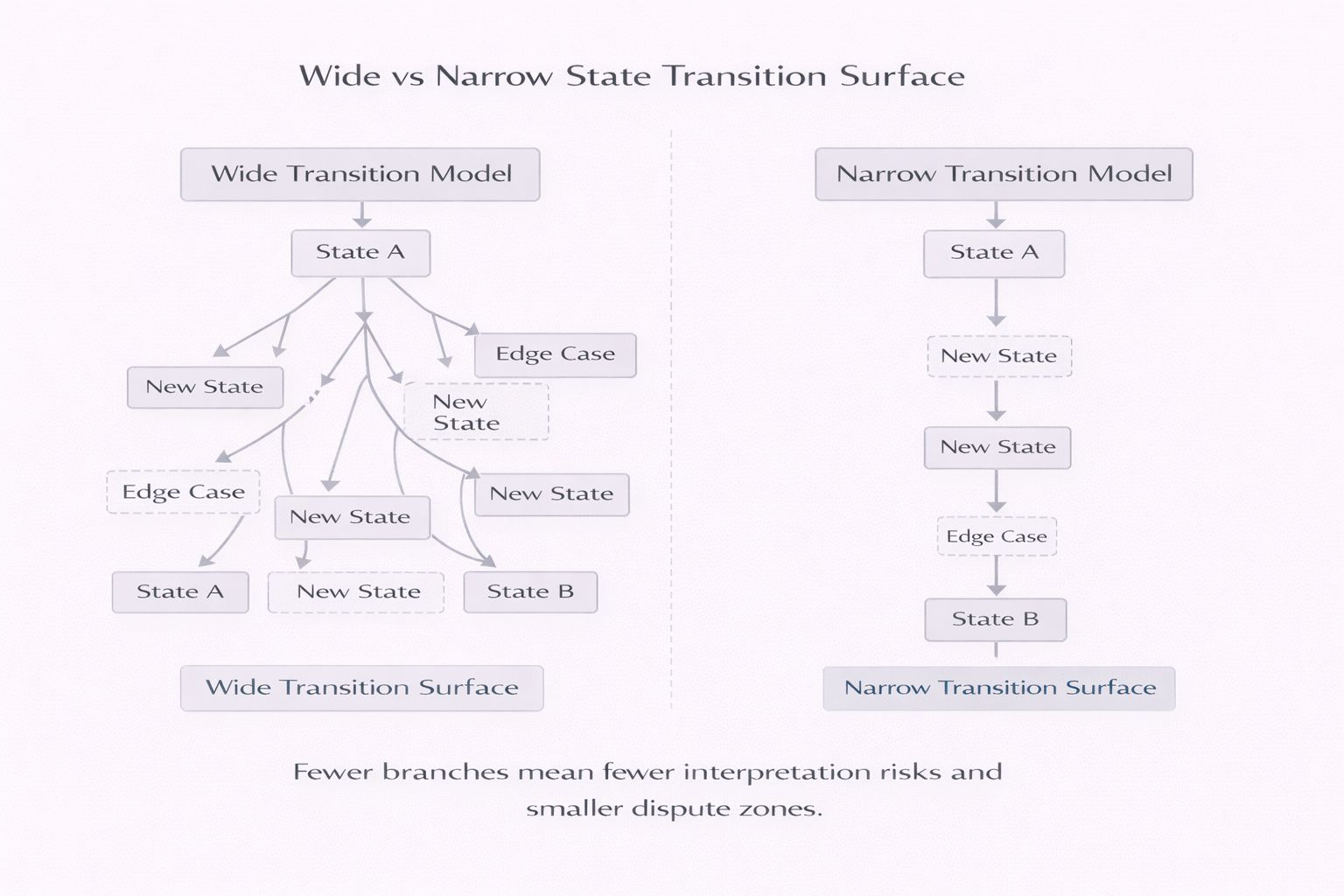

Most chains talk about state transitions as a neutral mechanism. Transactions come in, state updates come out. As long as validity rules are satisfied, the system is considered correct. But the width of what counts as a “valid” transition varies a lot between architectures, and that width matters more than people think.

Plasma appears to make a deliberate bet here. Keep state transitions narrow, tightly specified, and hard to reinterpret once deployed.

I did not always see why that matters. Earlier in the market, flexibility felt like strength. The more kinds of transitions a system could support, the more future proof it seemed. You could extend logic, patch behavior, support edge cases, and keep applications running even when assumptions changed.

After watching several systems mature, I started noticing the pattern on the other side.

Wide state transition logic invites interpretation. Interpretation invites exceptions. Exceptions invite coordination. Over time, what started as a clean execution model turns into a growing list of special paths and conditional handling. None of them look dangerous alone. Together, they make behavior harder to reason about under stress.

What Plasma seems to be doing is cutting that problem off early.

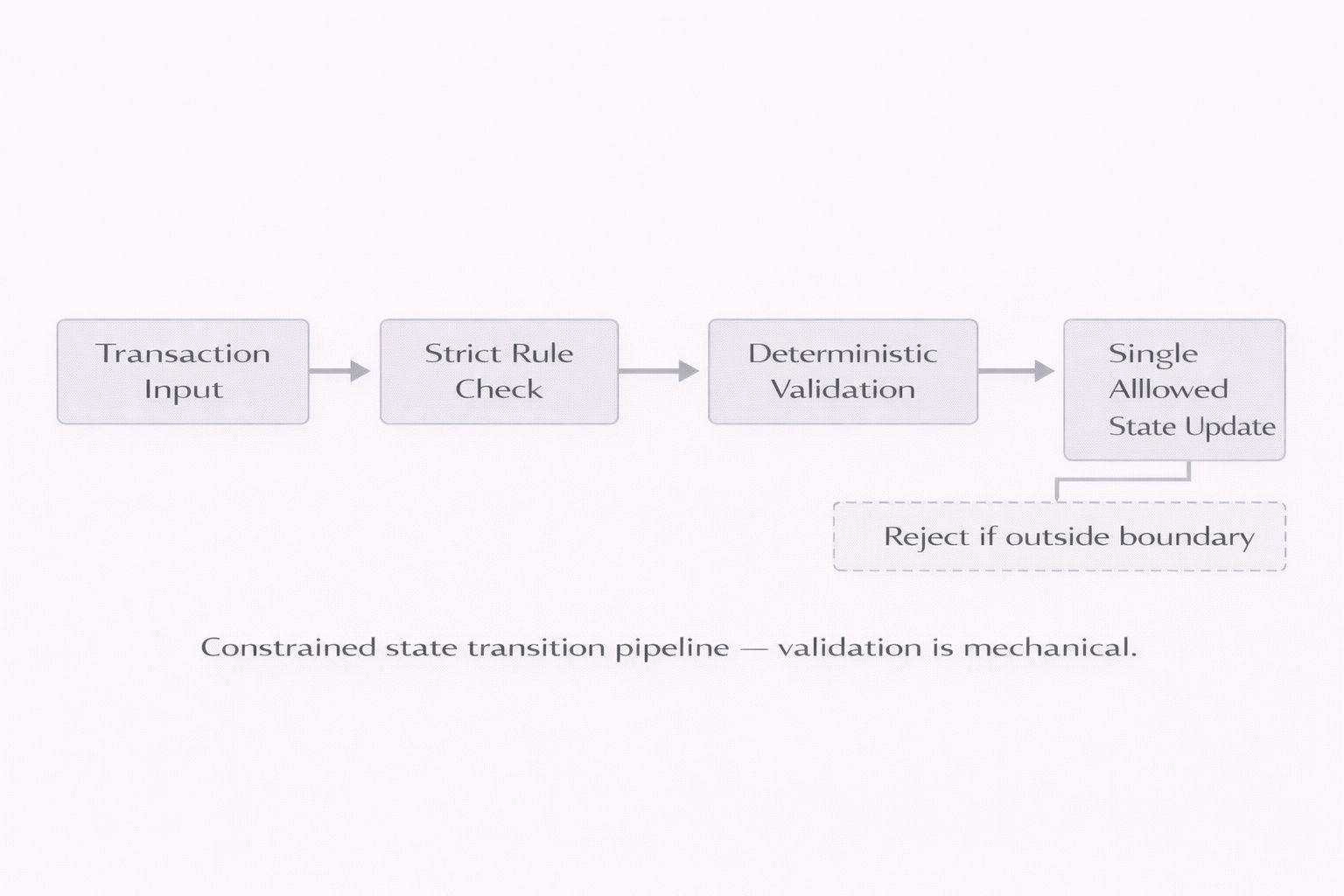

Instead of optimizing for expressive transitions, it optimizes for legible ones. Fewer branches, fewer dynamic paths, fewer “this is valid depending on context” cases. A transition is either inside the box or outside it. There is less gray zone for humans to debate after the fact.

From the outside, that can look limiting. Developers used to rich execution environments may find it restrictive. You cannot rely on clever transition logic to smooth over design mistakes at higher layers. If your application model does not fit, the base layer does not stretch to accommodate you.

But that restriction carries a benefit that only becomes obvious later.

When state transitions are narrow, dispute surfaces shrink. Validator enforcement becomes more mechanical. You reduce the number of moments where someone has to ask, “What did the protocol really mean here?” That question is more dangerous than it sounds, because it is where technical validation quietly turns into social judgment.

I have seen cases where two implementations both passed their internal checks but disagreed at the edges. The protocol text allowed interpretation, and interpretation turned into disagreement. Once real value is moving, those disagreements are not academic anymore. Someone takes the loss.

Narrow transitions reduce that exposure.

Another effect is on upgrade pressure. Systems with very expressive transition models often need frequent refinement. New edge cases appear. Behavior needs clarification. Parameters get tuned. Each upgrade may be reasonable, but the cumulative effect is execution drift. The system you audit in year one is not the system you are running in year three.

Plasma’s tighter transition model pushes against that drift. New features have to fit inside existing rules instead of expanding them easily. That slows innovation at the base layer, but it also slows entropy.

There is a real trade off here, and I do not think it should be hidden.

Narrow state transitions reduce protocol agility. They raise the cost of experimentation. Some categories of applications become awkward or impossible to implement directly. Builders have to carry more responsibility at higher layers instead of leaning on base layer flexibility.

Personally, I see that as an architectural statement rather than a weakness.

It says the base layer is not trying to be everything. It is trying to be dependable within a tight scope. The design priority is not maximum expressiveness. It is minimum ambiguity.

The longer I stay in this market, the more I value that priority. Not because it is exciting, but because it ages well.

Expressive systems shine early. Constrained systems reveal their value later, when edge cases accumulate and pressure becomes continuous. At that point, the question changes. It is no longer what the system can do. It is how predictably it behaves when pushed repeatedly.

Narrow state transitions help answer that question in advance.

I do not read this as Plasma trying to win on features. I read it as Plasma trying to reduce the number of arguments the system can have with its own rules. That is a quieter goal, but for settlement oriented infrastructure, it may be the more durable one.