Decentralized storage has always promised resilience, but resilience in theory is different from resilience in real life. In the real world, machines reboot, operators disappear, networks lag, and nodes drop without warning. Most systems treat these events as failures to be patched over with more replication and more bandwidth. Walrus takes a different stance. It assumes disorder from the start. Its RedStuff encoding design does not try to fight node churn. It designs around it. That philosophical shift matters more than it first appears. Instead of aiming for perfect uptime, RedStuff treats imperfect conditions as normal and focuses on how efficiently a system can recover when things inevitably go wrong.

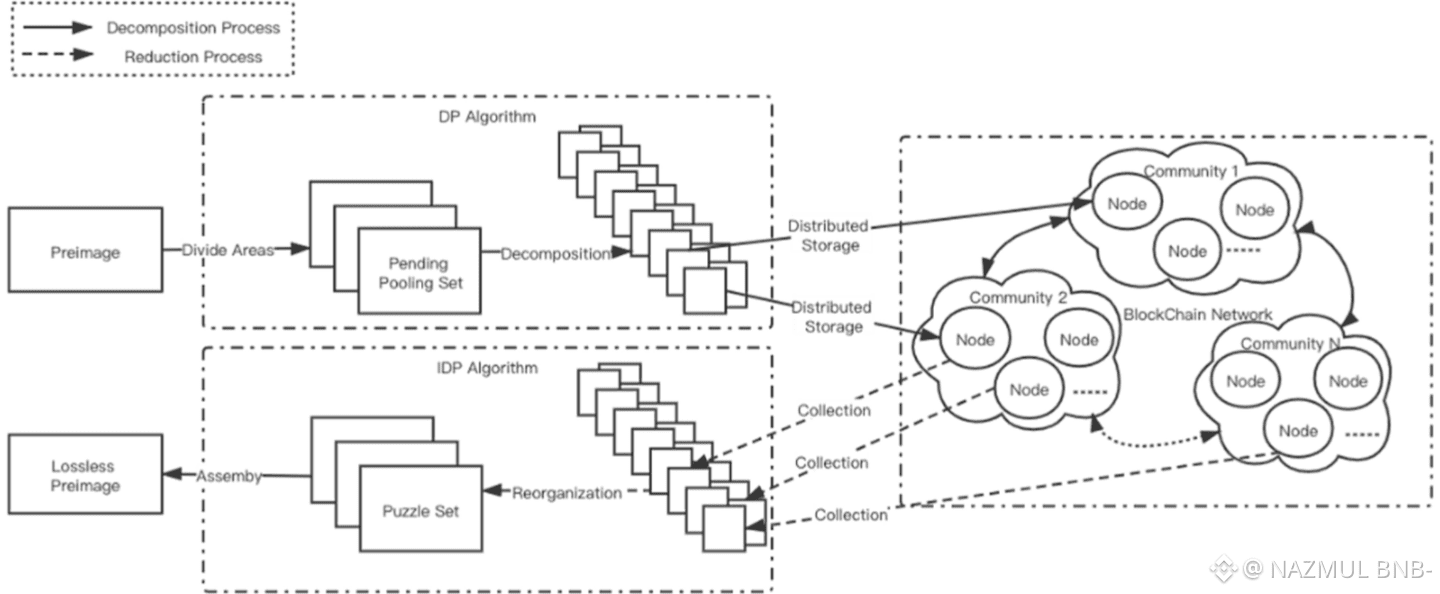

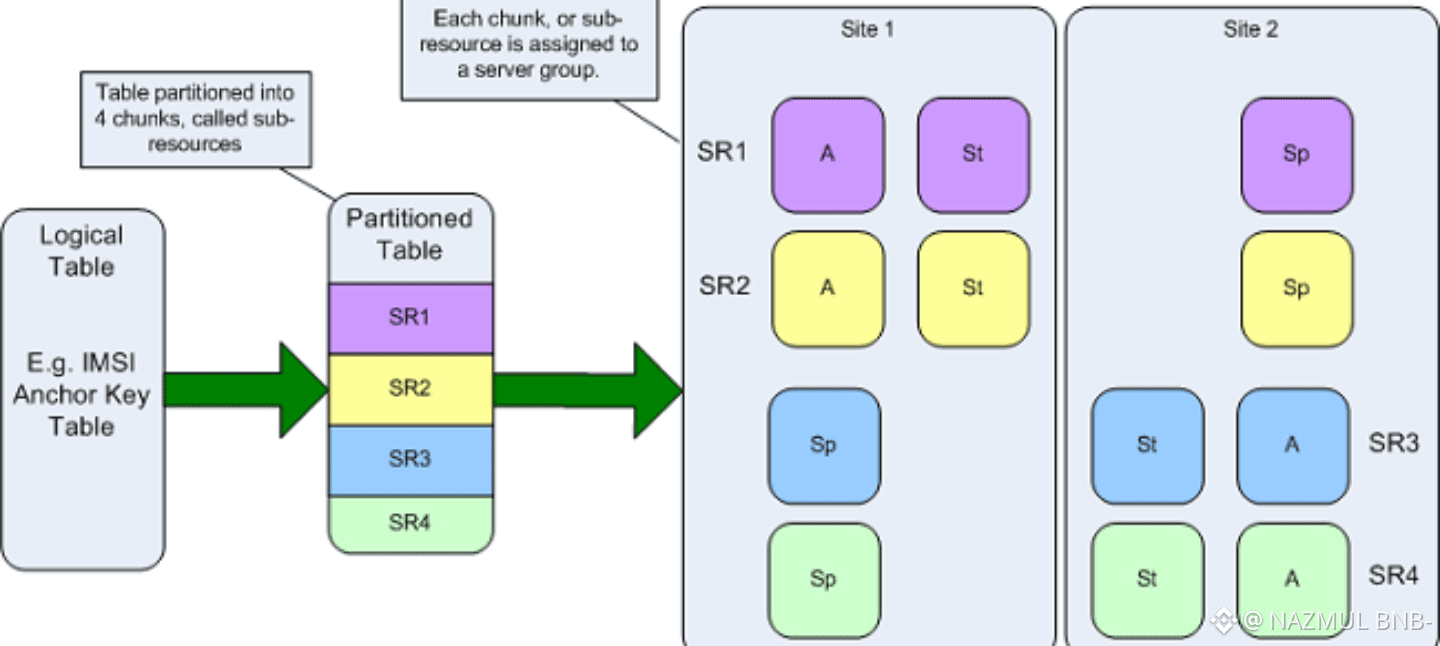

At a basic level, RedStuff breaks files into many small encrypted pieces and spreads them across the network. This is not new. What is different is how those pieces are structured and repaired. RedStuff uses a two dimensional erasure coding layout. You can imagine a file laid out like a grid rather than a single row. Each node stores a small slice that overlaps with others in multiple directions. The practical effect is simple to explain. You no longer need every piece to rebuild a file. As long as enough pieces remain, the original data can be reconstructed. If some nodes vanish, the system does not panic. It calmly fills in the missing parts using what is still available. Like finishing a puzzle even after losing a few pieces, as long as the overall pattern holds.

What makes this design meaningful is how it behaves under stress. In many storage systems, losing data fragments triggers heavy recovery work. Entire files may need to be re-downloaded and re-uploaded just to replace a small missing portion. That costs time and bandwidth and puts pressure on the network exactly when it is already unstable. RedStuff flips that cost structure. It only pulls what is needed to repair what is missing. Recovery effort scales with the damage, not with the size of the original file. This is a subtle difference with large consequences. Over time, lower recovery overhead means the network spends more effort serving users and less effort fixing itself.

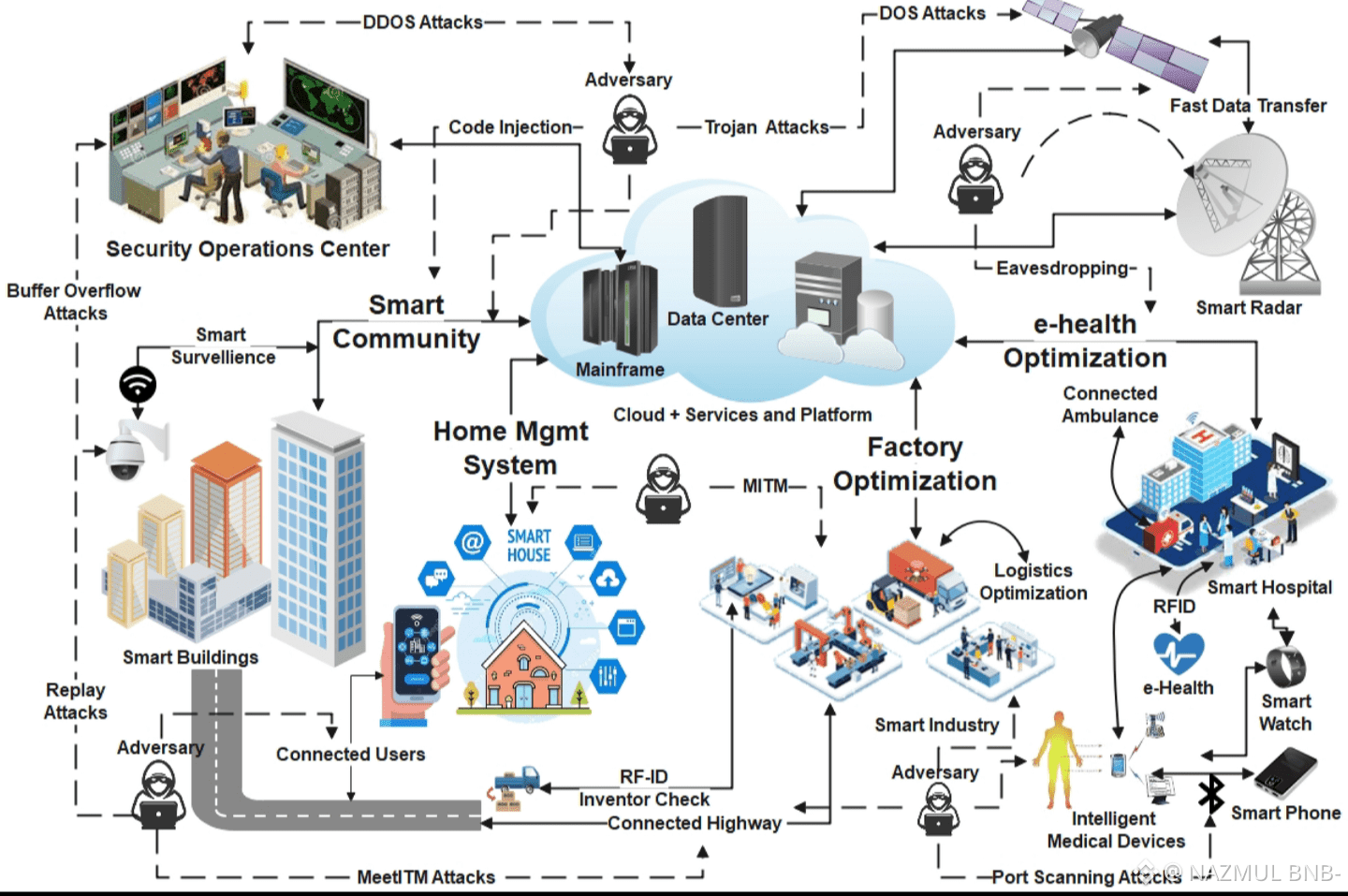

This approach also reflects a more realistic view of decentralization. In open networks, operators vary widely in reliability. Some run professional infrastructure. Others use spare machines or home setups. Expecting uniform performance from such a mix is unrealistic. RedStuff accepts that some nodes will always be offline or unreliable. Instead of forcing strict uptime guarantees, it designs redundancy so that no single node is critical. Failure is absorbed quietly, without drama. That makes the system more forgiving and, paradoxically, more dependable over long periods.

Another important aspect is efficiency. Redundancy is necessary for durability, but excess redundancy becomes waste. Walrus positions RedStuff as a way to achieve strong availability without extreme replication. The claim is not that redundancy disappears, but that it is organized more intelligently. By spreading encoded data across two dimensions, the network gains many local repair paths rather than relying on a few global ones. This allows missing fragments to be reconstructed using nearby data instead of pulling from far across the network. Even if those claims need continuous validation at scale, the direction is sound. Smarter structure beats brute force copying.

From an educational standpoint, RedStuff also helps clarify an often misunderstood point about decentralized storage. Reliability is not just about how many copies exist. It is about how quickly and cheaply a system can heal. A network that can recover small losses efficiently may outperform a heavily replicated system that bleeds bandwidth during every repair. This reframes how we evaluate storage designs. Instead of asking only how much data is stored, we ask how the system behaves on its worst days. That is usually where real costs hide.

Analytically, RedStuff feels less like a feature and more like an infrastructure mindset. It does not promise perfection. It promises adaptability. It does not assume honest behavior and stable hardware. It assumes chaos and builds guardrails around it. That makes it easier to reason about long term sustainability. Systems that rely on ideal conditions tend to look strong in demos and fragile in production. Systems that assume failure often age better. They become quieter over time, not louder.

Of course, no encoding scheme is a silver bullet. Questions remain around placement, coordination, and behavior under highly correlated failures. If many nodes disappear together due to shared infrastructure or incentives, any system will feel strain. RedStuff reduces the blast radius of random loss, but it does not magically erase all structural risks. The important point is that it narrows the problem. Instead of fighting every failure mode at once, it focuses on the most common and costly one: routine churn. That focus alone is a sign of maturity.

In the broader picture, RedStuff suggests a shift in how decentralized infrastructure is being designed. Early systems chased availability by stacking redundancy. Newer systems are starting to chase efficiency under pressure. That change is subtle but meaningful. It reflects an understanding that decentralized networks will never be clean or stable in the way centralized systems can be. They succeed not by eliminating failure, but by making failure cheap to handle.

Seen this way, RedStuff is not just a technical upgrade. It is a statement about priorities. Storage should degrade gracefully. Recovery should be proportional. Operators should not be punished for normal behavior. If Walrus can continue to prove these ideas in real network conditions, RedStuff may end up remembered less for its math and more for its attitude. It treats instability as a fact of life, not a flaw to hide. In decentralized systems, that may be the most realistic innovation of all.